Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

March 2, 2026

Sir James Young Simpson

Posted on August 1, 2024 | in Uncategorized | by lbeattieIn light of the upcoming 300th anniversary of the University of Edinburgh’s School of Medicine in 2026, volunteer Ash Mowat looks to the archives to find out about Sir James Young Simpson.

In this blog we shall explore some items in the University of Edinburgh’s Heritage Collections, featuring the work of the pioneering medical figure of Sir James Young Simpson.

Simpson (1811-1870) was born in Bathgate (West Lothian, Scotland).[1] He became an undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh in 1825 (aged just 14), and after several years elected to study medicine as his specialism. By 1830 he had become an approved practitioner with the Royal College of Surgeons, and in 1832 achieved the MD (Doctor of Medicine Higher Degree). He began practices as a GP in Edinburgh, and at aged just 28 became the Professor of Medicine and Midwifery at the University of Edinburgh.[2]

(Dr Simpson’s family home in Bathgate where he grew up, situated on the left).[3]

Despite his academic achievements, in his personal life Simpson suffered from episodes of depression but managed to recover and continue to expand his medical knowledge and expertise. Given his specialisms of Midwifery and surgery, an obvious area of his interest became the pursuit of a suitable anaesthesia to use. In 1847 he employed the use of Ether during a complex childbirth, but was not content with the efficacy of the treatment. He and several of his colleagues then began the hazardous tasks of experimenting on themselves with various, often toxic, substances. Later that year Simpson had acquired some Chloroform and after sampling this and witnessing its instantaneous inducement of unconsciousness, went on to promote his “Announcement of a New Anaesthetic Agent” that received widespread coverage in media and medical publications. It was soon adopted and widely used and acclaimed during surgical and complex midwifery cases, but was not routinely used during childbirth due to then unhelpful views on the “naturalness” of such pain during labour. Whilst Chloroform was by far the most effective and least risky anaesthetic then available, it was by no means entirely safe. However, it paved the way before safer alternatives could later be developed, and in the process greatly alleviated useless pain and suffering for so many.[4] In addition, in his services to to advancement of midwifery, Dr Simpson helped develop improved surgical instruments such as “Simpson’s forceps” and the Air Tractor, the first vacuum extractor to help with problematic childbirth.

As a result of his achievements in this filed, he was appointed Her Majesty’s Physician in 1947, and in 1866 became the first practising Doctor in Scotland to receive a Baronetcy. Simpson has a bust held at the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh, together with a sculpture of him located in Princes Street Gardens. Almost fifty years after his death, in 1916 the Simpson family bequeathed his former family home and former GP Surgery on Queen Street Edinburgh to the Church, and it is currently managed by the Charity Crossreach, to deliver free counselling and support for those affected by substance misuse issues.

Notes of Midwifery lectures given by Sir James Young Simpson taken down by George Dickson.[6]

I viewed this handwritten notebook of Dr Simpson’s lectures on midwifery and use of chloroform as notated by one of his students, located within the University of Edinburgh Library Heritage Collections. It offers a fascinating insight into the then available procedures, some of which were radical and advanced for the period, but also reveal the limitations of the technology during this time which have mercifully since been surpassed.

On a section on the gestation period for successful live human childbirth, the term abortion is used in place of what we now refer to as miscarriage or premature birth where the infant does not survive. Simpson observes that any child born at six months or earlier during this era was not viable and able to be saved, resulting in death, whereas nowadays 89% of children born at 27 weeks can be expected to survive, often without lasting disability or complications. In his lecture Dr Simpson helps dispel the myth that the size of the child at birth is any determinant of their general health and their life achievement prospects, citing that Sir Isaac Newton was small at birth, but became a pioneer and polymath in Physics, Mathematics, Astronomy and other fields, and lived until age 84.

Dr Simpson explains the vital need to carefully observe the patient during every childbirth to watch out for any emergence of problems and intervene swiftly and appropriately where they occur, cautioning that: “If you don’t and accident arise of complications, you get the blame for it. Therefore, set aside all engagements. In country may have to carry opium, in town nothing is required but a bottle of chloroform”.

Simpson goes on to challenge some assertions that have critiqued the efficacy and appropriateness of using chloroform as an anaesthetic. Under the charge that to do so is an unnatural medical intervention and that pain in childbirth is simply a matter for people (women only, obviously) to endure, he responds:” I mitigate suffering as well as prevent death”, hereby dismissing that charge and demonstrating the value of chloroform. Answering the accusation that using anaesthetic causes complications, Simpson responds “It stops convulsions. I cured a child of convulsions after 24 hours chloroform.” No anaesthetic including chloroform is every entirely safe, but this example of successful prolonged use of the drug is revealing as towards its comparative safety.

Another challenge that implies that using chloroform may precipitate bodily or mental diseases he simply rejects as “nonsense”. Interestingly he concedes under the Theories of how anaesthetics work to remark “can’t be explained”. Perhaps surprisingly this remains the case, with a full understanding on the exact mechanisms of general anaesthesia not yet established.[8]

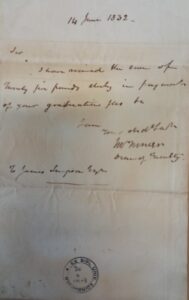

(The above receipt for Dr Simpson’s fees following graduation. Totalling £25.00 for seven years of university arts and medical training, this is equivalent to around £3500.00 today, which seems surprisingly affordable).

Extracts of letters of Margaret Buchanan Robertson relating to treatment by Professor James Young Simpson 1857-1959.

I viewed the above, held by the Lothian Health Services Archive within the University of Edinburgh Library.[9]

The letters were written by Margaret Buchanan Robertson to her mother in Australia. Her mother had immigrated to Australia in 1822 with Margaret born there, only to return to Edinburgh with her sibling in 1826 aged 24. The letters reveal much about her health issues and of the treatment received as a patient of Dr Simpson.

In a letter of 9/3/1857 she comments, “providence has been very kind and many blessings I enjoy which I strive to be thankful for, but from bad health I am often sadly depressed, languid and ill, but lately I am better, and the Doctor says he hopes to see me quite well and strong, but I am not as sanguine as he is. It is an internal complaint which causes a constitutional delicacy. I have been under the celebrated Dr Simpson’s care for three years and must say he has done me much good and without receiving a proper reward for all his kindness. Twice I have staid (sic) with his family home that he might watch the complaints, but it must run its course.”

In a further letter of 11/5/1857 she writes: “Mrs Hogg has been a kind friend to me and loves me as a sister. I must tell you how we became known to each other. We were both attending the great Dr Simpson and you must know you can only see him by the ticket. She had number 40 and I had number 7, which would admit me several hours before she would. She told me her sorrows and also that she had lost her little girl a few months before…She had been advised to consult the greatest man of the age, so she had come and hoped he might be able to restore her and if God thought fit, she might be blessed with an heir. I exchanged my ticket (with her) and it was with reluctance it was taken. She saw the Doctor and he cheered her telling her that if her general health was restored, she might have a family, but she must not be impatient. She remained a week under his care and in about a year she wrote asking me to come and visit her and just before leaving for home she told me that I might expect to hear of the arrival of a wee stranger, so this is the foundation of our friendship”.

Some years later in a letter of 16/2/1859 she observes: “My health I am thankful to say is much better since I had a very severe attack of nettle rash (Hives). The eruptions were all over my body, fortunately my face excepted for the marks are still on my hands, arms and body. My kind friend Dr Simpson said he thought my health would ultimately be better, but that I must be very careful of myself. He has been like a father and has refused to take renumeration from me saying “wait until you are cured dearie” It is most kind of him, he is most generous and many are the good deeds he does that will never be known in this world, but in the next he will receive his reward.”

The testimony in these letters brilliantly demonstrate the expertise, compassion and generosity of Dr Simpson and of the importance of his specialism upon the lives of many women under his care. In summary, Simpson devoted his professional career in the field of alleviating pain and suffering, and in saving lives that could otherwise be lost in childbirth or surgical procedures. I should like to thanks all staff at the University of Edinburgh Heritage and Lothian Health Services Archives for enabling access to these documents, and to Laura Beattie (Community Engagement Officer) for supervision and support.

[1] https://ourhistory.is.ed.ac.uk/index.php/Sir_James_Young_Simpson_(1811-1870)

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Young_Simpson

[3] Archives Space Public Interface | University of Edinburgh Archive and Manuscript Collections Seven photos relating to Sir James Young Simpson (Section DC.2.85s/DC.2.856

[4] https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/heritage/college-history/james-young-simpson

[5] https://www.crossreach.org.uk/our-locations/simpson-house-counselling-recovery-service

[6] Collection: Notes of midwifery lectures given by Sir James Young Simpson, taken down by George Dickson | University of Edinburgh Archive and Manuscript Collections

[7] Premature birth statistics | Tommy’s (tommys.org)

[8] General anaesthesia – Wikipedia

[9] Collection: Robertson, Margaret Buchanan | University of Edinburgh Archive and Manuscript Collections

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Leave a Reply