Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

February 24, 2026

The Achievements of Professor Charlotte Auerbach

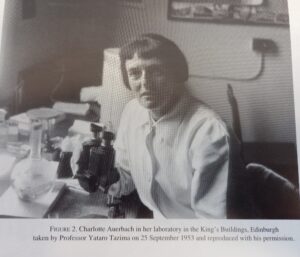

Posted on March 8, 2024 | in Archives, International Women's Day | by lbeattieIn celebration of International Women’s Day, our volunteer Ash Mowat looks to the archives to see what can be discovered about the achievements of scientist Professor Charlotte Auerbach.

In this piece I am writing to remark upon files from the University of Edinburgh’s Heritage Collections on the pioneering German geneticist Charlotte Auerbach.[1] I come at this as a volunteer and enthusiast so not with any academic expertise in here scientific field.

Charlotte Auerbach (1899 to 1994) was a German Jewish scientist, specialising in the field of genetics. [2] She was born in Krefeld Germany, and from a family with a rich heritage in academia, education and the arts. Her grandfather Leopold was a renowned physician in human anatomy, whilst her father, perhaps her greatest direct influencer of her later chosen studies, was a biologist.

A Genetics Society of America obituary of her, found in the archives, describes how she first had her interest sparked in childhood. “Her interest in Biology was kindled when by her father who took time to teach her to identify birds and plants, as well as the constellations in the night sky. Her interest in Biology was not fostered in School, however, and she received no formal instruction in the subject (in School) after she was fifteen.” Of her later time as a Lecturer at the University of Edinburgh it states “Often with little more than a short list of one word topics to guide her, she held the undivided attention of successive classes of undergraduates year after year. She spoke with authority but never minded being questioned.”

She went on to study biology and chemistry across several German Universities, excelling in her studies and commencing a career in teaching the sciences at School level. The rise of the Nazi government precipitated repeated obstacles to her rights to continue to work in education. These obstacles and the ever increasing threats posed to Jews by a brutal anti-Semitic regime persuaded her to leave Germany. She then settled in Edinburgh.

The Auerbach family tree above demonstrates the astonishing educational achievements of the extended family. Sadly, there is a tragic reference to the suspected death by suicide pact of her father’s sibling and wife in 1933, cited as brought about by persecutions of the Nazi government.

Auerbach received her PhD from the University of Edinburgh in 1935 at the animal genetics institute, where she would remain until her retirement, involved in both research and in teaching University students.

The area which was to prove her chief subject of expertise was mutagenesis, this being when an organism is affected by mutation precipitated either naturally or via an external influence, such as chemicals, x-rays or ultraviolet light etc. [3]

In a lecture given in May 1957 in New York City to the Radiation Research Society, she refers to her breakthrough work in Edinburgh in the 1940’s, kept secret until some years after the end of the Second World War, that for the first time established a direct agent for mutagenesis, that of how mustard gas can cause cellular mutations in fruit flies.

The importance in this work was to reach better understanding of and protection from mutations. Agents that could potentially cause mutations could also be essential tools in medicine, such as x-rays and radiotherapy, therefore one factor in her research was to help best identify optimum levels of exposure and dosage of any mutagens, such as to maximise the best possible treatment outcome, whilst minimising the risk of destructive damage to tissues and risk of inducing cancers.

In a paper of July 1959 entitled “a discussion of mutagenic specificity” dated July 1959, she comments, “I am an evolutionist, I believe that the DNA and the two main components are intimately and, probably, spiritually conjoined”. In describing how mutagenesis functions she states “the mutagen must enter the cell and penetrate the nuclear membrane. Once inside the cell further genetic change may affect the mutagen, which then interacts with the hosts DNA.”

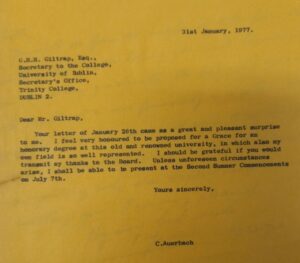

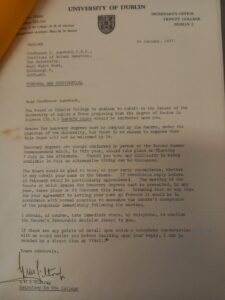

(The images above outline the granting to Auerbach of an Honorary Degree from Trinity College Dublin in 1977, one of many awards and accolades that she received throughout her life.)

Despite her many achievements I noted some instances where she could perhaps be overly self-critical of her work. In a letter to Dr Muller dated January 1946 she comments “My slow and plodding way of trying the same thing over and over again by different methods.” But later she recognises that this is surely the only way to undertake rigorous and effective science by remarking “After all, it is the only way which satisfies me and one can’t very well work in any other matter.”

Her methods were validated further in a written record of the cancer specialist Sir Anthony Haddow[4] from 1975. He observes of Auerbach “From the beginning I have had the highest opinion of Dr Auerbach’s great qualities as a researcher and teacher. In addition, I have a special reason for interest and respect, because of her pioneering in the field of chemical mutagenesis, contributions which have had an invaluable impact upon the closely related field of experimental carcinogenesis. Dr Auerbach was indeed, I believe, the first geneticist to demonstrate the mutagenic effect of chemical agents around 1940, and her method of analysis….has thrown much light on the mechanisms of gene mutation”.

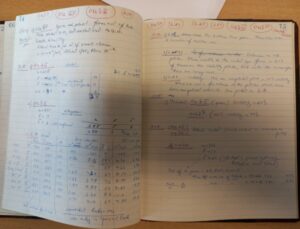

The above image from an undated hand written note book of Auerbach, further demonstrates the meticulous design of her experiments and thorough annotations. Such highly refined processes including use of control substances are essential in enabling proven results that can be replicated.

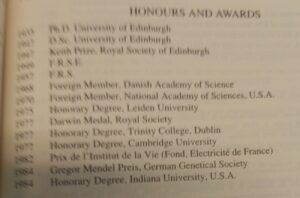

The above summary of Auerbach’s lifetime catalogue of honours and awards is evidence of the sustained expertise of her specialised field of genetics, and how widely her achievements were recognised and valued.

Outside of her academic prowess, Auerbach had a reputation for generosity and philanthropy. In a letter after her death from Professor Nicola Loprieno to Professor Geoffrey Beale at the University of Edinburgh, he remarks “I wish, apart from the great scientific contributions Charlotte Auerbach left, that everybody remembered the deepest humanity she was gifted with. I should like to point out, as I personally witnessed it, how for many years she supported through an international organisation, and an Italian youth from Sicily. She provided for his living and education, from primary school to the Scuola Tecnica Agraria. His name is Angelo Alecci. After graduation, Mr Alecci became Professor at the Istituto Tecnico Agraria. So grateful was Mr Alecci that he named one of his daughters Charlotte Auerbach Alecci.”

And Professor Beale wrote “She had a great love of children…in fact she did unofficially adopt two boys. One (Michael Avern, the other being the aforementioned Mr Alecci) was the child of a German speaking woman who lived in Lotte’s house in Edinburgh as a companion.” He notes that Auerbach left her home to Michael Avern when she moved into a care home.

In conclusion Charlotte Auerbach, or Lotte to her loved ones, devoted a lifetime of work to accomplish considerable advancements in the critical understanding of how genetics function and how such knowledge can improve healthcare. The circumstances that precipitated her having to flee Germany were obviously tragic and traumatic, however she proved to be a pioneering global asset in her chosen science. She made Edinburgh her home and a much admired and loved Lecturer at the University of Edinburgh, enhancing its prestige and bestowing her knowledge upon a whole new generation of students eager to learn from her and continue the better understanding and exploration of genetics.

[1] https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/85712

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Auerbach

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Leave a Reply