Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

July 27, 2024

Mysterious Songs from an Arabic Manuscript by Sarah Osama

Posted on January 27, 2024 | in Archives, Manuscript Collections | by lbeattieThe following post has been written by Sarah Osama, who has recently completed an internship looking at our Manuscripts of the Islamicate World and South Asia (MIWSA).

*Please note that all translations in this article are my own and are not meant to convey wholly accurate, line-by-line translation. Rather, they attempt to capture the subject matter and tone of the original text for the reader.

A little known fact about the University of Edinburgh’s Heritage Collections is that it boasts the third largest university collection of manuscripts pertaining to the Islamicate world in the United Kingdom- just after the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. This impressive but long under-researched collection presents an enormous task to those working on cataloguing, curating and researching the 700+ manuscripts, which was renamed in late 2022 from the Oriental Collection to Manuscripts of the Islamicate World and South Asia (MIWSA).

While the focus of my internship with the MIWSA collection was to digitise partial legacy data, I had the opportunity to work on a number of uncatalogued material, and this included numerous manuscripts bequeathed to the University by Robert Blair Munro Binning (d. 1891), an administrator with the East India Company in the 19th century. With the exception of sevenentries in legacy data from a 1925 descriptive catalogue by Muhammed Hukk et al., the vast majority of Binning’s 40+ manuscripts are not yet properly catalogued, and Kitāb muntakhabāt min al-kutub al-mukhtalifah al-‘Arabiyyah, or the Book of Selections from Various Arabic Writings (Or Ms 526) sits among these largely unknown texts. Almost no information is available on this manuscript’s production or origins, and one particular piece of vital information that we do not have is the dating of the manuscript. However while it is undated, we know that it must have been extant by the late 19th century when Binning passed away.

Kitāb muntakhabāt is a seemingly unique collection of iconic literary and religious texts from a wide geographical and time range in the Arabic language. The contents of the manuscript include stories like Sinbad from A Thousand and One Nights, a selection of chapters from the Quran, the first Mu‘allaqah of the famous pre-Islamic Arabic poems known as al-Mu‘allaqāt al-Sab‘ li Imruʼ al-Qays, a collection of Aghānī, and finally, a seemingly random collection of writings, possibly correspondences and business-related matters on the final pages.

If you are familiar with Middle Eastern culture and literature, you would have instantly recognised some of these titles. However, the “Aghānī” section is as obscure as its title suggests. Aghānī in today’s Arabic usage generally refers to songs, but it can also refer to poems. The word aghānī is in plural form, the singular form being ughniyah. Unlike A Thousand and One Nights or the Mu‘allaqāt, the poems that form the aghānī section remain a mystery and complicate what at first appears to be a self-explanatory collection of iconic Arabic texts. Significantly shorter than its preceding sections, the Aghānī are full of religious and cultural references that go as far West as North Africa, making us question the provenance of the manuscript which would otherwise be assumed to have originated in India or Iran due to Binning’s career. This article will examine some of these aghānī and conclude with possibilities for a different understanding of the compilation and acquisition of Kitāb Muntakhabāt.

The Aghānī

During my initial examination of the manuscript, my attention was immediately drawn to the “aghānī” section. The short and easily digestible rhyming couplets make for a light read, and the subject matter- love and heartbreak- is ever relatable and entertaining. The aghānī also stand out for their anonymity as they do not come with any titles or references to their source. This is odd in light of the manuscript’s conventions. The stories in the first section of the manuscript consistently provide titles, and the Quranic chapters and mu‘allaqah, despite being widely identifiable on their own, are still titled. Up to this section, I had no trouble identifying the contents for cataloguing purposes, but upon completing quick searches of the poetry online, I was surprised by the obscurity of these poems.

However, the poems themselves provide some clues to their context as we notice several cultural, historical and religious references. For example, Layla of the famous lovers in Arabic poetry ‘Layla wa Majnun’ makes an appearance in the second half of the third ughniyah:

یا رب ان حملتني فوق طاقتي

فحمل لیلی بعض ما فی فوادیا

واال فساوی الحب بینی وبینها

اعیش

کفافا ال عل ّي وال لیا ً

یقولون لیلی بالعراق مریضة

فیالیتني کنت الطبیب المداویا

اداوي لیلی من سقام عرفته

وما یعرف االسقام اال المداویا

This roughly translates to:

O God, if You are to burden me with that which I cannot bear,

Then burden my heart with Layla

If not, then equalise the love between us

They say Layla is sick in Iraq

If only I were the healing the doctor

I would heal Layla from the sickness of knowing him

Only the healer knows of sickness

There are also multiple religious references interspersed throughout the aghānī. The line above that roughly translates to ‘Oh God, if You are to burden me with that which I cannot bear’ is a nod to a verse in the Quran (‘Our Lord, and burden us not with that which we have no ability to bear’ Quran 2:286). There are also more subtle borrowings from Quranic language, such as a curious line in ughniyah 5:

تسقی من ماء دافق

It is watered with rushing water

This line appears to combine two separate phrases in the Quran: ‘it is watered’ (من تسقی (echoes Quran 88:5 while ‘with running water’ (دافق ماء من (echoes Quran 86:6. Finally, there are intriguing references to North African history and culture within ughniyah 5 that will be explored below.

Identifying the Aghānī

In my research for a manuscript likely acquired within the context of the East India Company’s activities, I was surprised when ughniyah 5 pointed to a North African origin. Various, but not all lines from ughniyah 5 match a poem on the Website Montadayat Jabala, a blog on the culture of the Jabala region of Morocco. According to the blog, this poem is commonly recited at weddings and joyous events, which could point to the use of the word aghānī (songs), as these poems may in fact be cultural songs.

Additionally, the final line in stanza 2 includes a historical reference, where ‘daughter of the Ṣanhājī prince’ references the Sanhaja, a historic Amazighen tribal confederation across various modern Northern and Sub-Saharan African countries:

ذبت کما ذاب الرصاص

لحمي علی عظمي یبس

من حبك یا عین الطاوس

بنت االمیر الصنهاج

I have melted like lead

The meat on my bones have wasted away

From your love, oh eye of the peacock

O daughter of the Ṣanhājī prince

Another clue to this poem’s North African origin lies in the first two lines of stanza 5, another match to Montadayat Jabala and which appears to be a prayer swearing upon the names of Ja‘far, Khālid, the Prophet, Aḥmad and Dāwūd:

وجعفر وخالد والنبي

احمد وداود یا ربي

اغفرلي امي وابي

نرجي

موالنا فضلك ُ

And by Ja‘far, Khālid and the Prophet

Aḥmad, Dāwūd, oh God

Forgive my mother and father

We seek your favour, our Lord

I found an almost identical couplet on an Algerian blog, where it suggests that these names are of local Sufi saints. It is likely that these lines reflect a convention of making a prayer within, or at the end of a poem or song, with the particular usage of local saints to call upon God situating it within a specific geographical and cultural context.

It is unsurprising that ughniyah 5 provided the most clues to its origins as it is by far the longest ughniyah in the section. Furthermore, this ughniyah is uniquely split into numbered stanzas, and may be a collection of smaller poems or parts of different poems grouped under one ughniyah. Considering that the subject matter appears to change between each sub-division of ughniyah 5 but contains several North African references throughout, this may be a collection of North African poems or songs.

The Aghānī and Contextualising Kitāb Muntakhabāt

What we know about the manuscript is that it clearly samples a variety of well-known texts in Arabic, most likely to showcase a range of iconic texts in the language with literary and religious significance. I believe there are two arguments that can then be made for the aghani section: considering the other texts in the manuscript, the aghānī must also showcase well-known literature, or inversely, the fact that this section does not identify its texts as the other sections do, perhaps this is a unique selection of more obscure literature. It is also possible that at least some of them may be found in the famous Kitāb al-Aghānī, which is an encyclopaedic collection of poems and songs by Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī (d. 967 C.E.). This could explain the title of the section, but would not explain why such texts would be so obscure on the internet and untitled in the manuscript.

Researching the aghānī has pushed me to reconsider the relationship of the compiler with the manuscript. It is very likely that the compiler’s selection of literature was a personal one, and furthermore, I think the selection could indicate the compiler or commissioner was from a Western background. The manuscript does not follow conventions one might expect from an Islamic context. For example, I would have expected the text to start with the Quranic selections out of respect for the holy text. One might even say that including the Quran with a selection of literary texts is itself a foreign understanding of the material. Furthermore, beginning the selections with A Thousand and One Nights suggests this particular text’s importance to the compiler, and the inclusion of iconic stories like Sinbad would be in line with what we know about European interest in the Thousand and One Nights that was blossoming in the 19th century.

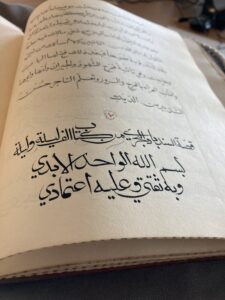

My suspicion that Binning himself may have commissioned or compiled Kitāb Muntakhabāt began with a curious note in an internal handlist that had designated this manuscript as ‘compiled by R. M. Binning’. While I could not find corroborating evidence for this note, I do think this is a strong possibility. Kitāb Muntakhabāt appears to be an original compilation and not a transcribed copy as there exists no preface or colophon, something which can be expected from older works. Additionally, and quite significantly, searching the given title online does not bring up any matches to earlier works, strongly suggesting its original compilation.

If Binning was indeed the commissioner or compiler of Kitāb Muntakhabāt, then this would better explain why selections of North African poetry appear in a manuscript assumed to be compiled or acquired in 19th century colonial India. Binning was a linguist of Arabic who published an Arabic grammar book in 1849, pointing to his great interest in the language. In addition to being stationed in India, he also travelled to the Levant, the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt, allowing the possibility that he acquired or compiled Kitāb Muntakhabāt in the Middle East instead of India.

It would be wonderful to have someone with more knowledge of these matters inspect these aghānī and the Kitāb Muntakhabāt more generally. More details about Or Ms 526 can be found here, and you can reach out to heritagecollections@ed.ac.uk to view this and other manuscripts at the University’s Centre for Research Collections.

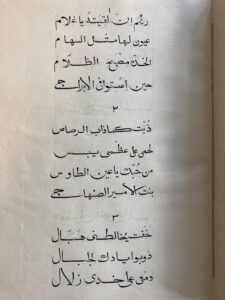

Appendix: Some highlights from the unidentified Aghani

Ughniyah 1:

شغلتم عنا فى محبة غيرنا

واظهرتم الهجران ما هكذا كنا

وعاهدتموا اال تخونوا فى الهوى

فلما انفضح الحب خنتم وما خنا

تدللتم حتى ملكتم قلوبنا

فلما ملكتم القلب قلتم ارحلوا عنا

سنرحل عنكم ان كرهتم وصلنا

يكون انقطاع الوصل منكم وال منا

فوهللا ما زال اشتياقي اليكم

والدخل التغميض/التخميض من بعدكم جفا

ترى تجمع االيام بينى وبينكم

وبشملنا شمل السرور كما كنا

ونرجو الذى تجرى االمور بحكمه

سيجمعنا بعد الفراق كما كنا

سالم عليكم ما ا ّمر فراقكم؟

فياليتنا من قبل فرقتكم متنا

You became involved with someone else and deserted me

You promised not to betray our love

Yet when the true nature of our love was revealed, it was you who had committed the betrayal

You were kind until you captured my heart

And after you captured it, you told me to leave you

I shall leave if you so hate our relationship

But let it be known that you ended the relationship, not me

And by God, I still miss you

I beg the One Whom everything happens by His will

To reunite us, as we were before our separation

I wish I had died before this separation

Note: This ughniyah is beautifully rhythmic when read aloud and succinctly conveys the experience of betrayal and heartbreak. Despite being our first- and one might thus assume to be a famous or important ughniyah, this poem is as of now unidentified.

Ughniyah 4:

يا سيدي محمد يا اهيف الغزالن

يا من وجنته يحكي الورد والنعمان

وقدك المعتدل يحكي غصن البان

تان

جل الذي صورك لقتلي يا فّ

Roughly translates to:

Oh my master Mohammad, oh slenderest of gazelles

Oh whose face speaks of roses and wildflowers

and whose stance is like the branch of the Moringa

How great is the One who created you, o tempter!

Notes: When I first read the opening line, I thought it may be a poem praising the Prophet Mohammad. However once I reached the teasing final line, I changed my mind! While it is common for male poets and singers to pine over someone in the masculine form, the inclusion of a male name is bold if indeed written by a man. Such sensual poetry would also be bold coming from a woman. Who wrote this poem? Is Mohammad a real person or a general representation of the lover?

Collections

Archival Provenance Project: Emily’s finds

My name is Emily, and I’m the second of the two archive interns that...

Archival Provenance Project: Emily’s finds

My name is Emily, and I’m the second of the two archive interns that...

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art....

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art....

Projects

Sustainable Exhibition Making: Recyclable Book Cradles

In this post, our Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses the recyclable book cradles she has developed...

Sustainable Exhibition Making: Recyclable Book Cradles

In this post, our Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses the recyclable book cradles she has developed...

Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Rehousing Books and Paper Bindings

In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers,...

Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Rehousing Books and Paper Bindings

In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers,...