Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

March 10, 2026

Scott, Globalisation and Race: father of ‘imperial romance’ or silent supporter of abolitionism?

Posted on July 30, 2021 | in Walter Scott 250 | by lbeattie

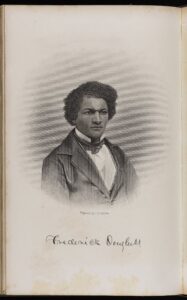

Engraving of a young Fredrick Douglass

When discussing what topics in relation to Walter Scott would be interesting and relevant to reflect upon at the beginning of my internship, one of the themes that was highlighted was that of globalisation. It seemed a bit strange to approach such in relation to Scott, seeing how as an international student who studied English Literature at the University of Edinburgh, I had only encountered Scott in a few lectures here and there. Nevertheless, as I spoke to Paul Barnaby, our resident CRC Scottish Archivist who has curated the exhibition, it became clear that Scott was influential as well as influenced by international revolutionary politics. Some allusions to Scott are less overt; for example, prominent African-American abolitionist statesman Frederick Douglass’ last name is inspired by Scott’s poem ‘The Lady of the Lake’.[1] With regards to more radical revolutionary readings of Scott, an interesting example I came across during this project (which is also highlighted in the online exhibition) is his influence on nationalism within Italy in the 19th Century against foreign domination of the peninsula. Clearly, they still resonate with a later audience as vehicles for exploring how literature and to an extent art (such as with Gaetano Donizetti’s opera Lucia di Lammermoor in 1835) can be used to discuss revolutions in a political and intellectual sense.

In truth, Scott himself was most likely troubled by issues of revolution. He was concerned about how these outside issues might influence Scotland if the sense of nationalism worked against the Union after witnessing the downfall of a number of ancient empires. The French Revolutionary Wars signalled the end of the Holy Roman Empire and the end of the Spanish Empire, the latter losing almost all of its colonies in the Americas. The Ottoman Empire was quickly finding it hard to suppress uprisings in Greece and Serbia. The Austrian and Russian Empires were fighting insurrection from Poland and Italy. There was a clear thread of nationalism and desire for self-determination within Europe at the time, which is ironic if one considers the extent of European imperialism across Africa and Asia. Scott’s work seems to indicate an understanding for the need to rebel against such empires, however he feared that the undercurrents of nationalism would lead to the fracturing of the British Union.

Nevertheless, Scott’s works do emphasise a need to preserve Scottish identity and traditions. He just simply found the idea of revolutionary nationalism as the Americans and French had pursued incompatible with the preservation of the Union.

As I continued my research into Scott and globalisation, I soon found myself in the territory of race and colonialism. The word ‘empire’ when associated with European countries is intrinsically tied to issues of racism, slave trade and colonial domination across the world. In more recent years, Scotland’s own role in transatlantic slave trade has become clearer and more widely discussed, working against the previous narrative which tended to present Scotland as uninvolved in such. Additionally, as the Black Lives Matter movement swept the world once again in 2020, a critical eye soon turned towards the way in which we preserve history of that time period and critical race theory not only in England but also Scotland.

Hence, I thought to myself: Is race a topic which can be associated with Scott? Was it an issue he wrote about explicitly or subversively in his works? Did he hold a stance with regards to the abolitionist movement?

While too young to understand in the moment, Scott would have known of the Knight v. Wedderburn trial in 1778 where an African slave, Joseph Knight, was freed from the employment of his Scottish master. It is also very unlikely that he was unaware of the notion of slave trade, seeing as he lived in New Town in Edinburgh, where many of his neighbours were likely involved in transatlantic slave trade. His training as a lawyer would likely have equipped him with knowledge with regards to the issues of property, which sadly included the ownership of slaves in this era. He also would have been aware of the movements across Europe for the abolition of slavery, as the Enlightenment ideals of ‘equality’ and ‘freedom’, which fuelled American revolutionaries, were incongruent with the idea of slavery. Scotland itself had a strong anti-slavery movement, which included groups such as the Edinburgh Committee for the Abolition of the Slave. In fact, Ian Whyte lists Scott as a subscriber of the Committee’s reprint of anti-slavery petitions in 1790.[2] He also would have witnessed William Wilberforce’s campaign against slavery and the Parliamentary abolition of slave trade which came to pass in 1833, just after Scott’s death; the former was inspired by Scott’ works.[3] Additionally, it would not be surprising if Scott followed the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) led by former slave Toussaint L’Ouverture against the French colonisers, as he had a distinct interest in the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars.

Nevertheless, when one looks critically at Scott’s work, there is no overt pro- or anti-slavery stance within his works. He was clearly much more concerned with the issue of nationhood and Scottish identity prevailing in the success of the Union than with the issue of abolitionism, which is simply a reflection of his privilege as a white, wealthy, heteronormative man. Critics such as Ian Duncan and Martin Green argue that Scott’s Waverley novels seem to provide a pioneering representation of military and imperial colonialism that it is only fitting that he be deemed the father of ‘imperial romance.’[4] Scott and his peers did not see imperialism in their time as the beginning of an empire, rather British expansion meant more opportunity for Scottish businessmen to extend their reach of free trade. Therefore, it would not be surprising that he did not consider the issues of slavery as important to address directly because it did not concern him with regards to Scotland’s preservation of culture or the protection of the Union; it was simply a by-product of the attempt of colonists to escape the oppression present within European monarchies and control of the free market.

Alternatively, as critic Carla Sassi has suggested in her paper about Scott and the Caribbean, there may be merit in observing how Scott may subversively address the issues of abolitionism, freedom and the rights of slaves in his works. She discusses how Scott’s works have an ‘implicature’ of silence, which very much aligns with the ‘(un)willed amnesia’ in Scotland with regards to their role in transatlantic slave trade in the 18th Century. She acknowledges that he, like Robert Burns, makes no clear stance in terms of abolition, however his silences within text could be read as a subversive way one such as Scott could present the unsaid and unsayable regarding his support of the abolitionist movement.[5] Her reading of his works presents an opportunity to critically re-evaluate his work and how he may perhaps be trying to use the ‘implicature of silence’ to further the abolitionist movement in Scotland.

It is unfortunate that Scott did not take an abolitionist stance, only referencing in passing the movement in his historical novels, however it is clear that modern readers are able to approach his texts with a new lens of criticism that may reveal more about Scott and his worldview. While it is not obvious initially to the reader, there may still be a possibility of discussion around Scott, globalisation and race within his works that can be further explored by re-examining contextual evidence along with his fictional works. Personally, as a female, Asian literature student who often found herself unrepresented by the large canon of white, privileged white men, it is exciting to find out that Scott may have been more revolutionary in his thoughts regarding race than previously thought.

Works Cited:

[1] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave: Written by Himself, Critical Edition. (Yale: Yale University Press, 2016), pp. 177.

[2] Ian Whyte, Scotland and the Abolition of Black Slavery, 1756-1838 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006), 87.

[3] Anne Stott, Wilberforce: Family and Friends (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 12, 174, 230, 258.

[4] Ian Duncan, ‘Scott’s Romance of Empire: The Tales of the Crusaders’, in Scott in Carnival, ed. by Alexander and Hewitt, pp. 370–79.

[5] Carla Sassi, ‘Sir Walter Scott and the Caribbean: Unravelling the Silences’ in The Yearbook of English Studies, Vol. 47, Walter Scott: New Interpretations (2017), pp. 224-240.

Written by Tessa Rodrigues, one of the Engagement Assistants for the Scott250 exhibition on Scott and Revolution.

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....