Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

July 26, 2024

The Industrial World: Scott’s Vision

Posted on July 29, 2021 | in Walter Scott 250 | by lbeattie‘We have accumulated in huge cities and smothering manufacturies the numbers which should be spread over the face of a country and what wonder that they should be corrupted? We have turned healthful and pleasant brooks into morasses and pestiferous lakes.’ – Walter Scott’s Journal.

The early 19th century was a period of many dichotomies. The divide between rich and poor, city and agrarian, the industrial and the baronial seemed starker than ever before.

Scott regularly drew attention to new machines and ideas in his novels. One such example is in Scott’s novel The Betrothed (1825). This features a meeting of shareholders looking to form a joint-stock company. Whilst this scene is intended to satirize the form of novels, it also brings attention to machine inventions. One such invention that is presented is the

“great patent machine erected at Groningen, where they put in raw hemp at one end, and take out ruffled shirts at the other, without the aid of hackle or rippling-comb—loom, shuttle, or weaver—scissors, needle, or seamstress. He had just completed it, by the addition of a piece of machinery to perform the work of the laundress.”

This describes a machine that could do the work of any laundress, or modern-day dry cleaner efficiently and instantaneously. Although this may seem common to those who own a washing machine, for Scott’s day it would have been a revolutionary idea. It also points out a slightly sinister idea. Machines like this could, and did, put the lives of workers (‘the work of the laundress’) at incredible risk. This demonstrates Scott’s interest in machines and his ability to draw them, subtly, into his narrative. However, his fascination with machinery certainly ran deeper than a passing interest.

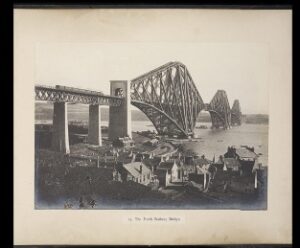

As scholar Professor Murray Pittock points out, ‘in Scott’s lifetime travel became ten times as fast, and before he died regular rail services had begun.’ It is possible that Scott’s fascination with revisiting the past was a way of negotiating the rapid changes of the present by visiting a more familiar territory.

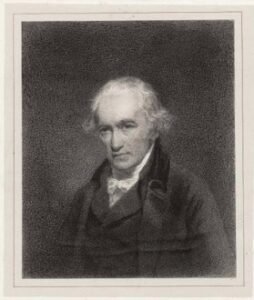

He also heavily acknowledged the impetus of change, industry and economy within his texts. In the introduction to his novel The Monastery (1820), Scott acknowledges his contemporary James Watt with great esteem. Watt, a pioneer of the steam engine and a prolific inventor, was someone whom Scott appeared to admire, describing him as “not only one of the most generally well-informed,—but one of the best and kindest of human beings.”

Scott’s praise of Watt also extended to machinery itself, stating

“machinery has produced a change on the world, the effects of which, extraordinary as they are, are perhaps only now beginning to be felt.”

This explains, with great awe, about the modern technology advances that shaped Scott’s day. However, there is also a sense of apprehension in Scott’s tone. In both the above introduction and in Scott’s Journal there is a slight hesitancy about the effects of industrialisation, which he senses will go further than anyone can predict. This links back to Scott’s love of history and revisiting historical sites: there is less ambiguity about what the present may hold.

This blog has been published in celebration of Edinburgh University Library’s new exhibtion, ‘Walter Scott and Revolution’, which celebrates the famed author’s relationship with contemporary and historical revolution.

Works Cited

Scott, Walter. The Journal of Sir Walter Scott, February 20, 1828.

Scott, Walter. The Betrothed (1825).

Scott, Walter. The Monastery (1820).

BBC, The Industrial Revolution, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/scottishhistory/enlightenment/features_enlightenment_industry.shtml, Date accessed: July 10, 2021.

Pittock, Murray. The Reception of Walter Scott in Europe (London: Bloomsbury, 2006).

Collections

Archival Provenance Project: Emily’s finds

My name is Emily, and I’m the second of the two archive interns that...

Archival Provenance Project: Emily’s finds

My name is Emily, and I’m the second of the two archive interns that...

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art....

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art....

Projects

Sustainable Exhibition Making: Recyclable Book Cradles

In this post, our Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses the recyclable book cradles she has developed...

Sustainable Exhibition Making: Recyclable Book Cradles

In this post, our Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses the recyclable book cradles she has developed...

Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Rehousing Books and Paper Bindings

In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers,...

Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Rehousing Books and Paper Bindings

In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers,...