Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

July 27, 2024

Losing the Heid… or not

Posted on October 10, 2019 | in Uncategorized | by NormanThe Parthenon Frieze at Edinburgh College of Art

Running around the walls of the Sculpture Court of Edinburgh College Art is a cast of the Parthenon Frieze, which was first acquired by the college’s predecessor institution, the Trustees Academy in the 1830s. The sculpture court at ECA was built specifically to house and display this cast.

Earlier this year I began looking at the frieze with a view to creating possible projects around it but, as I compared it with images of both the original marbles (now housed in the Acropolis Museum in Athens, the British Museum and the Louvre) and other cast collections, differences began to emerge. Two sections immediately caught my eye – the casts of Sections VI and VII of the East Frieze.

This is a cast of Section VI, as displayed in the Acropolis Museum, taken from the original version displayed in the British Museum.

Compare that with the one at ECA – shown below

The differences in Section VII are also striking.

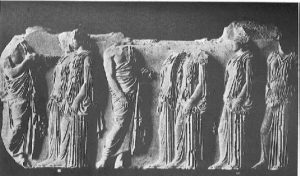

The original marble, on display in the Louvre, looks like this…

ECA’s cast, on the other hand looks like this!

So why the differences?

From the ECA records, it appears that Section VI was cast while the original was still on the Acropolis, made in 1787 by order of the French ambassador to the Sublime Porte in Constantinople, Count Choiseul-Gouffier. This version is also displayed at the Skulpturhalle in Basel, which has a complete set of casts from the Parthenon.

The original slab, taken from the Acropolis by Lord Elgin, is in the British Museum and on its website it displays the following text:

“These figures were sadly mutilated shortly before Lord Elgin’s men arrived on the Acropolis in 1801. They can be reconstructed with the help of casts from moulds taken by the French diplomat Le Comte de Choiseul–Gouffier.”

This would appear to verify that the cast of Section VI is original. The real mystery was Section VII, not least as yet more versions exist. One, copies of which are in Glasgow School of Art, the Met in New York and Cornell University collections (fig 1), shows the woman second from the right with more hair than the original, while another, from the Caproni Cast Collection in Boston (fig 2), shows a different head on the figure on the left to the one on the ECA version.

Fig 1 – Cornell Cast Fig 2 – Caproni Cast

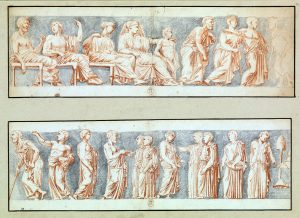

The ECA records suggest that the cast had been restored. Both Sections VI and VII of the ECA originate in the Louvre, though we have no acquisition date. The original slab appears to have been found beneath Parthenon by L. S Fauvel in 1784, a few years later than Section VII, so the question was whether this cast is as it was originally discovered or a later, restored version. The only known drawing of these pieces showing them in place on the Parthenon was made by Jacques Carrey in 1674 (Fig 3). The drawings made by the architects Revett and Stuart in 1751 for their Antiquities of Athens books, appear to show that this section was already missing from the Parthenon, as there is a sizeable gap in their sketch of the East Frieze. Their drawings were made after the explosion in 1687, which destroyed much of the building. The accuracy of Carey’s drawings have been questioned but from them it is easy to see differences in the hairstyles of the figures in Section VII.

Fig 3 Drawing by Jacques Cary

The original slab, along with a number of casts, was transported from the Acropolis to Piraeus and then shipped to Marseilles in 1797, from where it was then moved to Paris. On arrival in Paris, however Fauvel was apparently angered to discover that the slab was missing its heads and insisted that they be found, implying that they had been lost in transit. However, in his personal papers, where he describes the find in January 2nd, 1789, Fauvel stated that the bas-relief only had two heads.

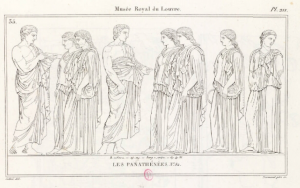

The slab was first displayed in what is now the Louvre in 1800 and the earliest drawing made in the museum was published in 1811 in A. L. Millin’s, Monuments antiques inédits ou nouvellement expliqués. No heads were shown. The earliest illustration with heads, didn’t appear until 1827 in Charles Clarac’s catalogue for the museum, Musée de Sculpture Antique at Moderne. A later edition of this catalogue, printed in 1841, contains the text, “all the heads of this bas-relief are due to a modern restoration.” This illustration is very similar to the cast held by ECA.

Fig 4. – Musée de sculpture antique et moderne Tome 2, première partie 1841 – Clarac

Half a century later, the 1896 catalogue for the Louvre contained a photograph of the slab with the heads once again absent (Fig 5).

Fig 5 – Musée du Louvre – Catalogue Sommaire – 1896

It appears that some restoration work was carried out around 1820, probably by Bernard Lange, who was then in charge of the Louvre’s restoration workshop, but there no evidence to confirm this. In researching this piece it transpired that the missing heads have long been puzzled over by archaeologists and art historians and indeed were the subject of a presentation made at a conference on the Parthenon frieze held in Basel in 1988. The presenters, Jean Marcadé and Christiane Pinatel, both from Paris, concluded that at some stage plaster heads had been added to the marble slab and that casts had been made, so it seems likely that this is the source of the cast at the College of Art. Completing broken sculptures was fashionable in the early part of the 19th century but by the second half this trend was no longer acceptable so the additions would then have been removed. However, they also stated that “the modern parts that were removed at the end of the last century have not been found,” so does this make the ECA version unique? Certainly, having looked at numerous publications and online resources, there are no other images showing a cast with heads and when I contacted Tomas Lochman, the curator at the Basel Skulpturahalle, with an image of the ECA cast, he described it as “really astonishing.”

There is a slim possibility that this cast was made while the slab was still intact on the Acropolis but all the evidence would suggest not. Nevertheless, while it may not be original, the ECA cast may the only one of its kind and therefore, as evidence of 19th century restoration techniques, still has some value. Moreover, if we scan the section we may be able to verify this once and for all, as each cast has lines running through them, showing how the original mould was created If these run continuously though the figures then it is indeed an original. Time will tell!

Norman Rodger

Projects Development Manager

Library & University Collections

10 October 2019

Collections

Archival Provenance Project: Emily’s finds

My name is Emily, and I’m the second of the two archive interns that...

Archival Provenance Project: Emily’s finds

My name is Emily, and I’m the second of the two archive interns that...

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art....

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art....

Projects

Sustainable Exhibition Making: Recyclable Book Cradles

In this post, our Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses the recyclable book cradles she has developed...

Sustainable Exhibition Making: Recyclable Book Cradles

In this post, our Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses the recyclable book cradles she has developed...

Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Rehousing Books and Paper Bindings

In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers,...

Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Rehousing Books and Paper Bindings

In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers,...