‘As recently as the 1970s, deaf history did not exist,’ writes John Vickery Van Cleve (Deaf History Unveiled, 2002), pointing out how, until recently, the history of deaf people and their lives had been overlooked as a viable area of study. Such neglect is a shame, because deaf history can be fascinating. What it encompasses is as varied as the different degrees of hearing loss; the word ‘deaf’ can be applied to every point on the audiological spectrum between mildly hard-of-hearing and profoundly deaf, and the experience of someone who was deafened in old age (and who has participated in majority ‘hearing’ culture all their lives) is entirely different to that of a person born completely deaf. While the former almost certainly experiences hearing loss as a loss, the latter may not see their deafness that way – it hasn’t been lost, since it was never there in the first case. Deaf people for whom speech is inaccessible are also more likely to use a sign language, which, as languages which have developed naturally in deaf communities across the world, are grammatically distinct from (but as complex as) spoken languages.[1] The lives of these deaf people and their communities are particularly absent from the historical record: sign languages are minority languages with no written form and thus no primary source material exists before the invention of film. There are few accounts written in English by deaf people themselves, as formal deaf education only began in Britain in 1760 and very few deaf children received an education until the mid-19th century. So-called ‘deaf and dumb’ or ‘deaf-mute’ people were typically pitied, disparaged or simply overlooked, and so deaf people were seldom written about by (hearing) record keepers in any detail, if at all. It is, Van Cleve continues, ‘as though the world in which deaf people grew up, married, worked, procreated, and educated their children was somehow unrelated to the larger world inhabited by people who hear.’ Trying to find evidence of deaf lives throughout history, and especially before the second half of the 19th century, can be a challenge; as with the histories of other minorities, we often have to seek tantalising details hidden in the historical record and extrapolate a wider picture from these.

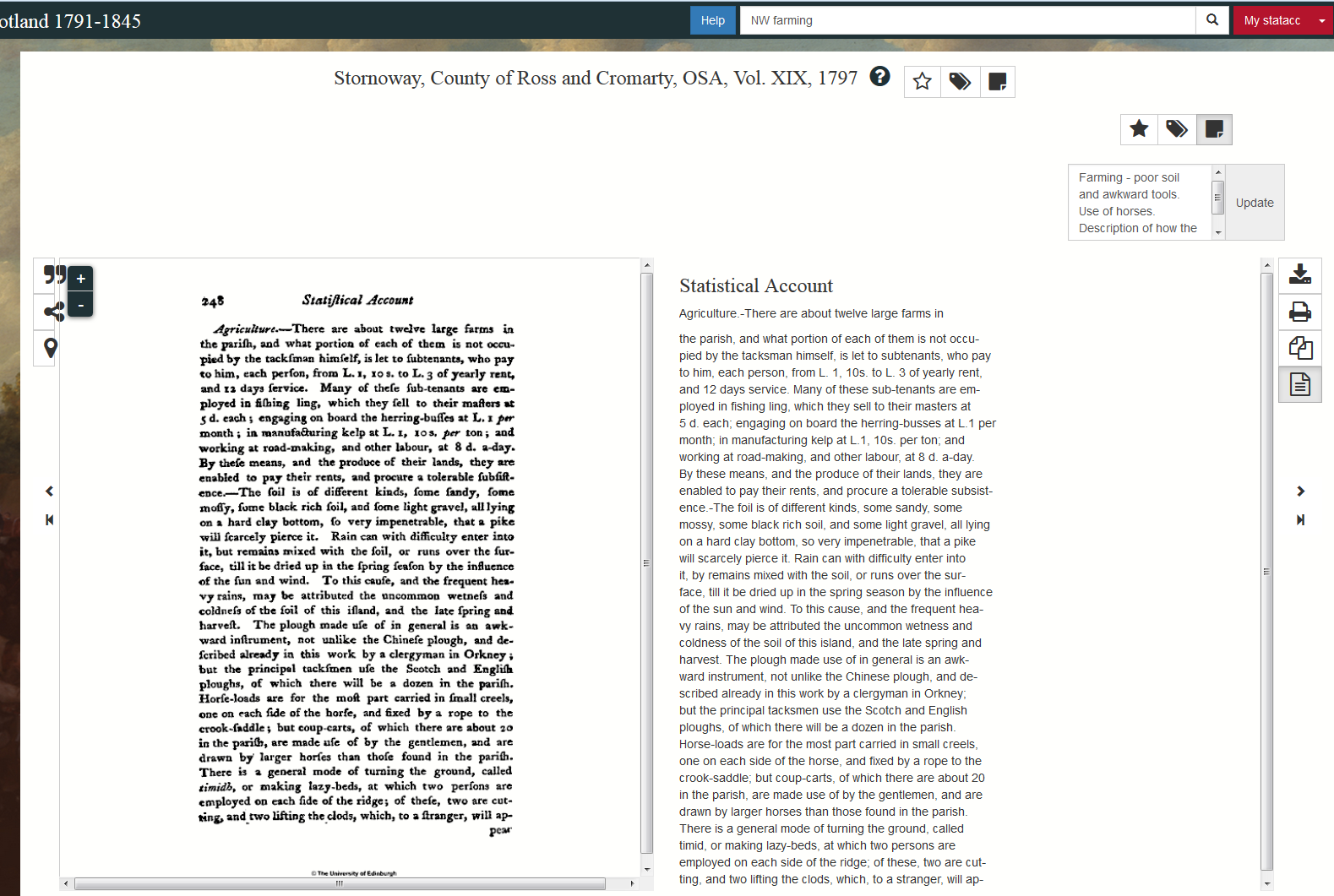

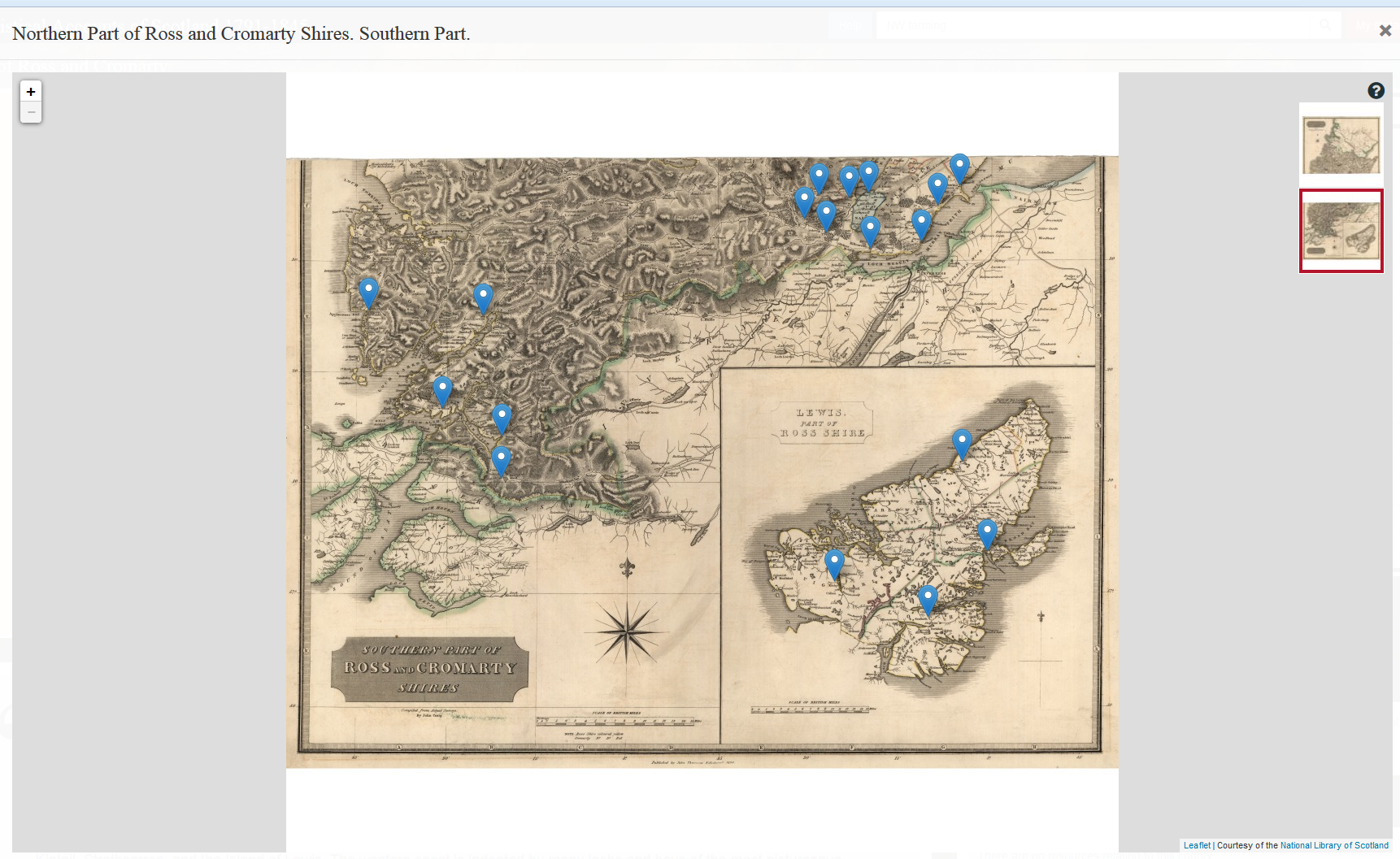

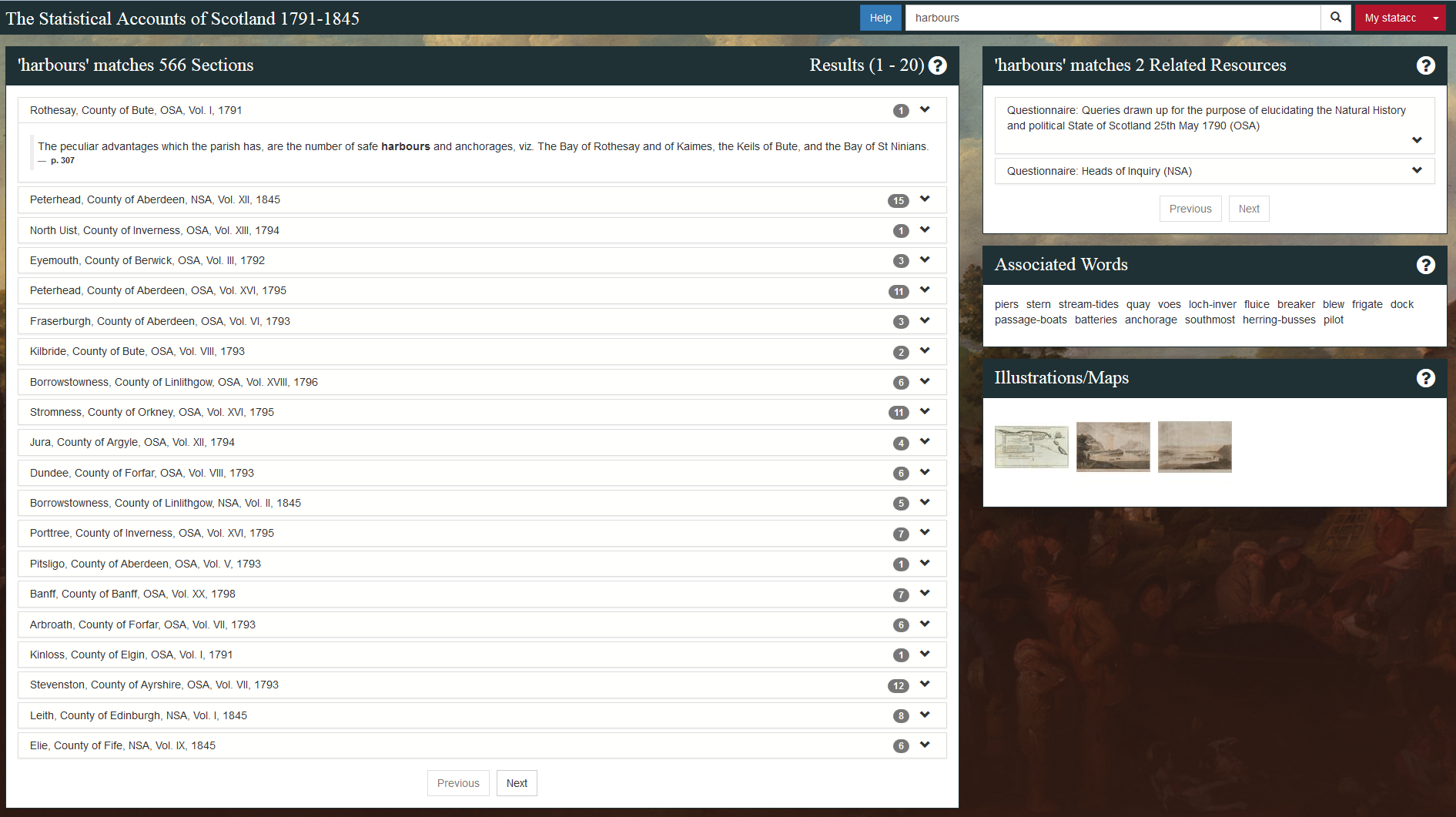

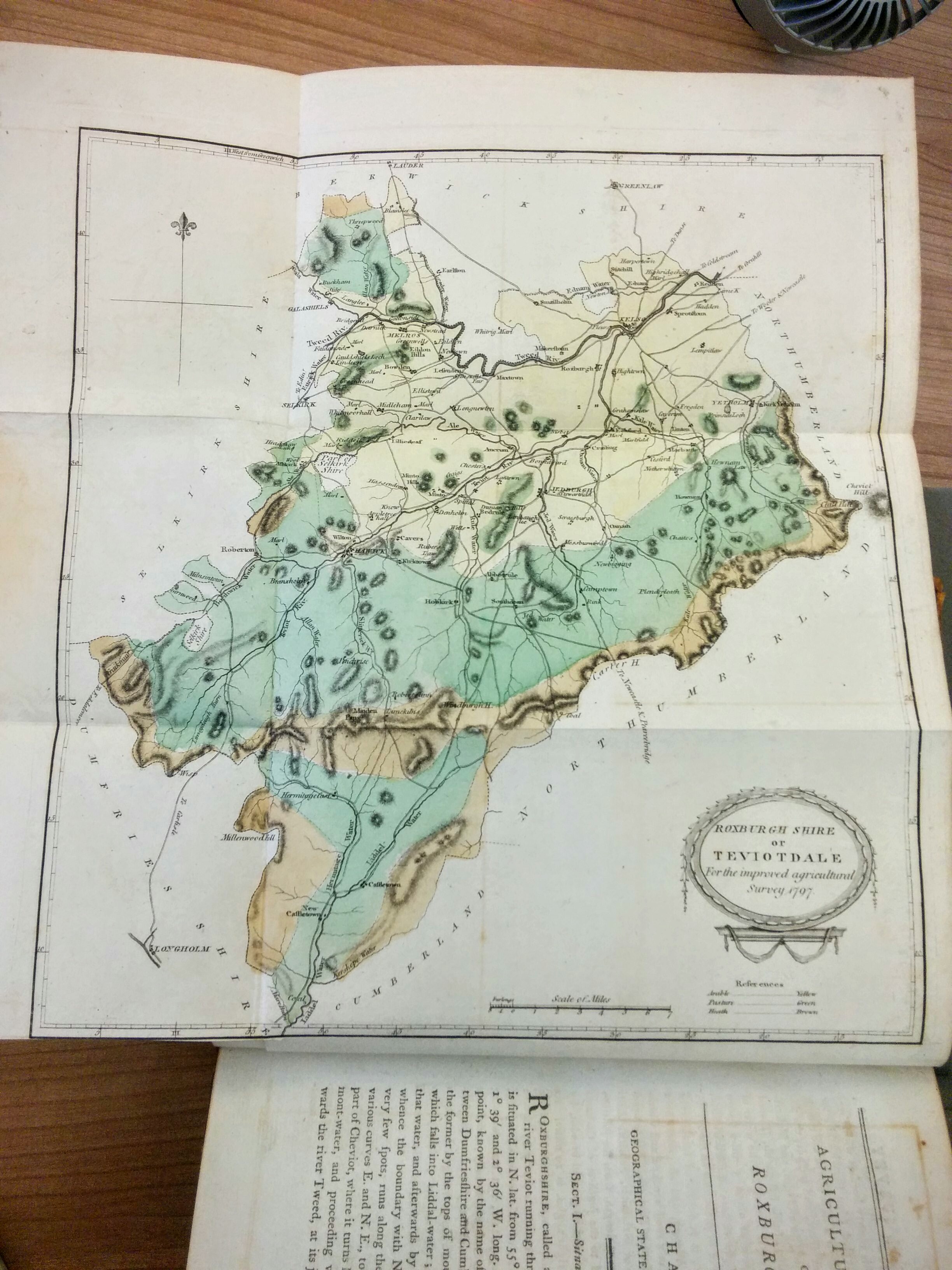

It was in this vein that the Old (First) and New (Second) Statistical Accounts of Scotland came to mind. For the last five years, I have taught on a course at the University of Edinburgh where the Statistical Accounts form the basis of the students’ written assessment – and, as my students will testify, my enthusiasm for the Accounts and the nuggets of localised social history they contain is, if anything, growing in intensity. So when I became interested in sign languages and the history of deaf communities, I immediately wondered whether there were any mentions of local deaf people in the Old and the New Accounts; thanks to the ‘search all text’ function, I was able to find them. There weren’t very many: out of 938 parishes, only four in the Old Statistical Account of 1791-99 (OSA) and 67 in the New Statistical Account of 1834-45 (NSA) mention ‘deaf and dumb’ people. Nor were these mentions very detailed: most merely state the number living in the parish, sometimes lumped in with other so-called ‘unfortunate’ demographics, as in the parish of Kilbarchan, Renfrewshire, which claimed seven ‘insane, fatuous, blind, deaf, dumb’ (NSA). Yet throughout the Accounts there are small glimpses of deaf lives that provide a useful springboard from which to investigate and piece together deaf history in the 18th and 19th centuries.

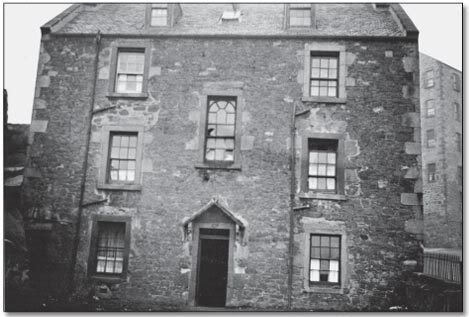

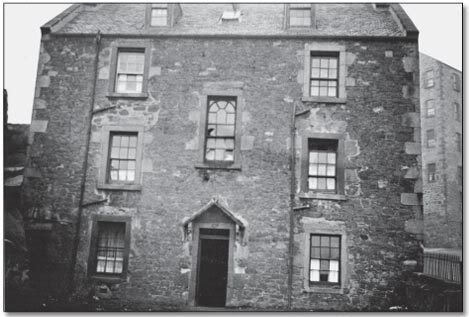

‘Dumbie House where Thomas Braidwood established the first school for deaf children, ‘Braidwood’s Academy for The Deaf and Dumb’ in 1760: By courtesy of Edinburgh City Libraries’

One example from the OSA comes from the parish of Aberdalgie in Perthshire. The minister writes that the local schoolmaster, Mr Peddie, had ‘acquired without any instructor, the rare talent of communicating knowledge to the deaf and dumb’ and had been teaching one ‘deaf and dumb’ boy from the parish. The boy had ‘never had another teacher’ – unsurprisingly, since the first school for the deaf, Thomas Braidwood’s Academy for the Deaf and Dumb (established in Edinburgh in 1760), had moved to London in 1783; there would be no other deaf school in Scotland before the Edinburgh Institution for the Deaf and Dumb was established in 1810. The solution in Aberdalgie appears to have worked well: Mr Peddie is described in glowing terms, and the young boy ‘has made a very great proficiency under him’ and ‘can read, write, and solve any question in the common rules of arithmetic, as well as most boys of his age who do not labour under his disadvantages.’

Education also features in the NSA. The Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Glasgow Institutions for the Deaf and Dumb were established early in the 19th century, yet these schools were expensive and over-subscribed. In the parish of Dunfermline in Fife, Rev. Peter Chalmers wrote in the NSA that, having been unable to raise enough money to send local deaf children to one of the Institutions, he had organised an ‘experiment’ in a local school:

A few years ago, four or five deaf and dumb children, belonging to the parish, were taught in Rolland School for two years and a half, by a deaf and dumb young woman … who had previously received a good education in the Edinburgh Institution.

Whereas it was (and is) often assumed that deaf education must be conducted by non-deaf tutors, Chalmers’ experiment had a young woman, Janet Robb, running an early prototype of a deaf unit in a mainstream school, working alongside but separately from the school’s main, hearing teacher of the non-deaf pupils. Although Chalmers’ experiment did not last long due to a lack of books and resources, he describes it as ‘succeed[ing] far beyond his expectations’, and declares himself convinced of the ‘entire practicability of the deaf and dumb teaching others.’ Chalmers was later able to send some of the children to the Glasgow Institution where they ‘made very rapid progress in their farther education, and in religious knowledge and character.’ Furthermore, in his self-authored, two-volume Historical and Statistical Account of Dunfermline (1844-1859), he claims that the Rolland School experiment directly inspired Edinburgh’s Deaf and Dumb Day School, which was established in 1836 by a deaf, sign language-using teacher, Alexander Drysdale, and catered to poorer children than could attend the Edinburgh Institution. Drysdale and Janet Robb had been schoolmates, and Chalmers reports that she and some of her pupils were invited to visit the fledgling school for three months, to encourage the pupils and to participate in the capital’s deaf community.

Rural deaf communities are harder to spot; eastern Fife may have had one, as, in the NSA, twenty ‘deaf and dumb’ people (including members of three deaf families) were recorded in five different parishes within 15 miles of each other. One Fife parish, Kilconquhar, is the only example where both the OSA and the NSA mention deaf parishioners; in the OSA, they are described as ‘abundantly sensible and active, and attend public worship regularly.’ Another rural example comes from the west coast, where the NSA for Portpatrick gives an insight into the lives of two ‘blind, deaf and dumb’ (or deaf-blind) siblings, living in a parish that included four other ‘deaf and dumb’ people. The 73-year-old sister and 66-year-old brother were both born deaf, but had been become blind in their 40s – possibly due to the genetic condition we now call Usher Syndrome. Deaf-blind people often use a tactile form of their sign language called ‘hands-on’, which is what Portpatrick’s minister may have meant when he wrote that the siblings ‘can be made to understand by means of touch what their friends find it necessary to communicate to them for their bodily comfort and personal safety.’ Their lives are described in a few short lines:

He can attend to the fire to supply it with fuel when it is required. She is remarkably particular as to her dress. Both can be made to understand when any one is present with whom they have formerly been acquainted; and when they are informed that the minister is present, they compose themselves, and assume a grave and serious aspect.

Outside official school and institutional records, it can be difficult to find details relating to the lives of ordinary deaf people, yet, as the Statistical Accounts of Scotland show, the details can be there beneath the surface, tantalising and incomplete. Human diversity has been a constant throughout history, and the lens through which we view history is forever widening beyond the traditional fixation with ‘the great and good’ to include the social history of working people, of women, of ethnic and other minorities – in short, to include the voices that may not have been heard or, in the case of deaf history, seen. There have been deaf people negotiating living in a hearing world throughout history and, although the record is vague, deaf lives can often be found hidden in the pages of ‘hearing’ documents. Through these, deaf history can be brought into existence.

Ella Leith

We hope you have enjoyed this post: it is characteristic of the rich historical material available within the ‘Related Resources’ section of the Statistical Accounts of Scotland service. Featuring essays, maps, illustrations, correspondence, biographies of compliers, and information about Sir John Sinclair’s other works, the service provides extensive historical and bibliographical detail to supplement our full-text searchable collection of the ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Statistical Accounts.

[1] Although we have no record of the signs they used, we know that deaf people were signing together in Ancient Greece, in the Scottish royal court in the 15th century, and in England and France in the 16th century. Today, British Sign Language (BSL) is used across the British Isles; however, throughout this blog I use the terms ‘sign language’ and ‘signing’ rather than referring to BSL, because the signs used in the 18th and 19th centuries may have differed considerably from the language as it is today.

Sources

Anthony Boyce and Pam Bruce, Loyal and True: The Life and Times of Alexander Drysdale (1812-1880) (Winsford: Deafprint, 2011)

Rev. Peter Chalmers, Historical and Statistical Account of Dunfermline (London: W. Blackwood and Sons, 1844-1859)

John Hay, Deaf Edinburgh: The Heritage Trail (Warrington: British Deaf History Society 2015)

Peter Jackson, Britain’s Deaf Heritage (Edinburgh: Pentland Press, 1990)

John Vickery Van Cleve, Deaf History Unveiled: Interpretations from the New Scholarship (Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University press, 1993)

Old Statistical Account: parishes of Aberdalgie, Kilconquar

New Statistical Account: parishes of Dunfermline, Kilbarchan, Portpatrick