Dr Elizabeth Hewat, first woman to receive a PhD from New College, who argued for women’s ordination

This blog post is written by Dr Lesley Orr, School of Divinity

In the year in which the Church of Scotland has welcomed the Very Revd Susan Brown of Dornoch Cathedral as its new Moderator of the General Assembly, the Church also celebrates the 50th anniversary of the ordination of women.

On Wednesday 22 May 1968, the Fathers and Brethren of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland voted by a large majority to extend eligibility of ordination to Ministry of Word and Sacrament to women, on the same terms as men. New College students, graduates and staff played a significant role throughout the half century when the question of women’s role, rights and equality in the Church was one of the most persistent and controversial issues for debate – not only in the Assembly but in wider Church and Scottish society. During this fiftieth anniversary year of women in ordained ministry, a commemorative project has been based at New College, supported by the Centre for Theology and Public Issues and in partnership with the Church of Scotland Ministries Council. Publications and photographs which tell a little of these events are currently on display in New College Library. But the story goes back much further.

The churches of the Scottish reformation, which were by 1712 finally established as Presbyterian, developed communities of practice which were thoroughly masculine in organisation and ethos. Ecclesiastical courts, offices and authority structures were the exclusive province of men. The hierarchy of church courts was composed of ordained ministers and elders. As Principal Martin of New College commented during a 1915 United Free Church Assembly debate, ‘our church is worked by its male classes, and that as a matter of principle’.1

That challenge was directly presented for the first time in 1926, when four Presbyteries submitted an overture to the General Assembly of the United Free Church to initiate legislation declaring the eligibility of women for admission to the colleges of the church, who, on completion of the prescribed theological studies, might be licensed to preach, and ordained to the ministry on the same terms as men. That year, Elizabeth G K Hewat, an outstanding scholar who also lectured at the Women’s Missionary College, became the first woman to graduate Bachelor of Divinity from New College. Proposing the motion, Prof James Young Simpson contended that ‘They had in New College a young woman who had beaten all the men in her class. It was extremely difficult to have to say to [her] “You have gone through your course in this admirable way, you are giving your life to service in the foreign field, yet we cannot put you on the same level as the men”’.

Opponents contended that the Holy Ghost, having inspired Paul to enjoin male headship and female submission, “would not now go against his own productions.” And it was claimed that: “the admission of women to the ministry would discourage a certain class of men of virile type from entering the profession. Who would be head of the manse?…surely it would mean the introduction of a celibate order into the church.” The motion was withdrawn in favour of an amendment that the time was not opportune for taking any steps.

But the claim of women was not going to go away, and soon the reunited national Church of Scotland was called upon to respond. In 1931, amidst considerable public interest and discussion, 335 women petitioned the General Assembly that ‘the barriers which prevent women from ordination to ministry be removed so that the principle of spiritual equality for which the Church stands be embodied in its constitution. Lady Aberdeen, who led the petitioners, entreated the Fathers and Brethren not to discourage those who heard the call to high and holy vocation, and called for support ‘in our endeavours to make the Church of Scotland truly the church of the people.’

Between then and 1968, a succession of commissions, committee and reports purported to deal with the place and ministry of women in the Church of Scotland. But the central matter of equal ministry was finally resolved between 1963 and 1968. Galvanised into action when the Panel on Doctrine reported in 1962 that it did not expect to take up its remit to consider women in the ministry ‘for some time’, Mary Lusk MA BD decided to take action. She was a woman of outstanding intellect – a graduate of Oxford who studied divinity at New College in the early 1950s. She was a recognised leader who represented the Kirk at the World Council of Churches Assembly in 1954, a deaconess who had built up a new congregation in Musselburgh, but had to hand it over to on ordained man. In 1963 she was working as associate chaplain at Edinburgh University – a position for which the holder would normally expect to be ordained. Lusk petitioned the General Assembly to have her call to ministry tested and, if recognised, to proceed to her ordination. Certain of her vocation, and already licensed to preach the Word, she believed the onus was on the Church to say why she was not fit to exercise a Ministry of Sacrament. Her speech was measured, informed, impressive, and New College students in the gallery cheered Lusk and her supporters. The Moderator, Prof James S Stewart, twice had to threaten to clear the gallery if they didn’t keep quiet.

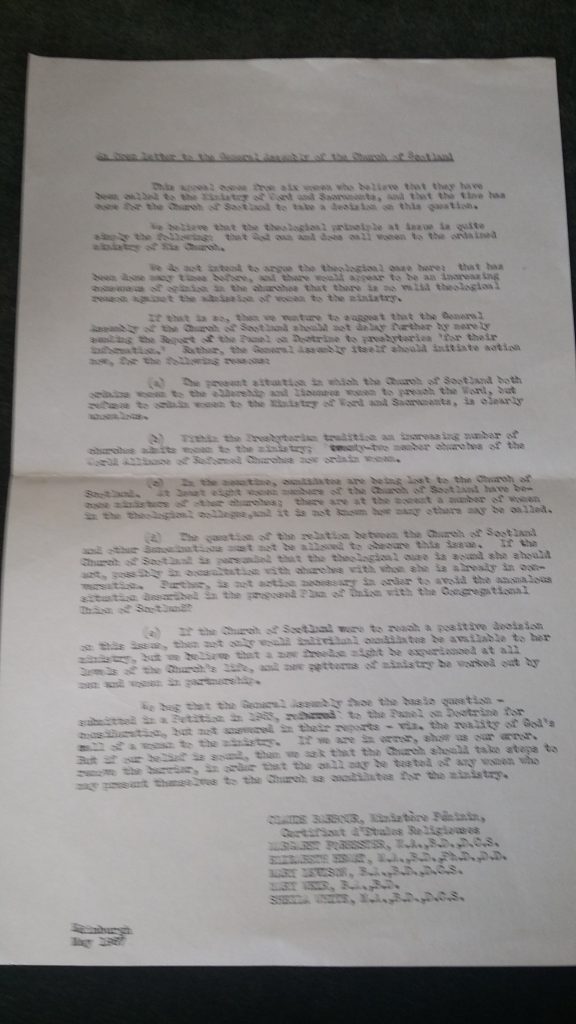

Open letter to the General Assembly from New College Alumnae

In 1967, the Panel on Doctrine produced yet another cautious report which simply laid out opposing theological positions and failed to recommend any action. An impressive group of six New College alumnae, including Dr Elizabeth Hewat, Mary Lusk (by now Levison) and Margaret Forrester, wrote an open letter to the Assembly, stating their belief that there was no valid theological reason to oppose admission of women, and urging a decision: ‘If we are in error, show us our error, but if our belief is sound, we ask that the Church should take immediate steps to remove the barrier, in order that the call may be tested of any women who present themselves as candidate.’

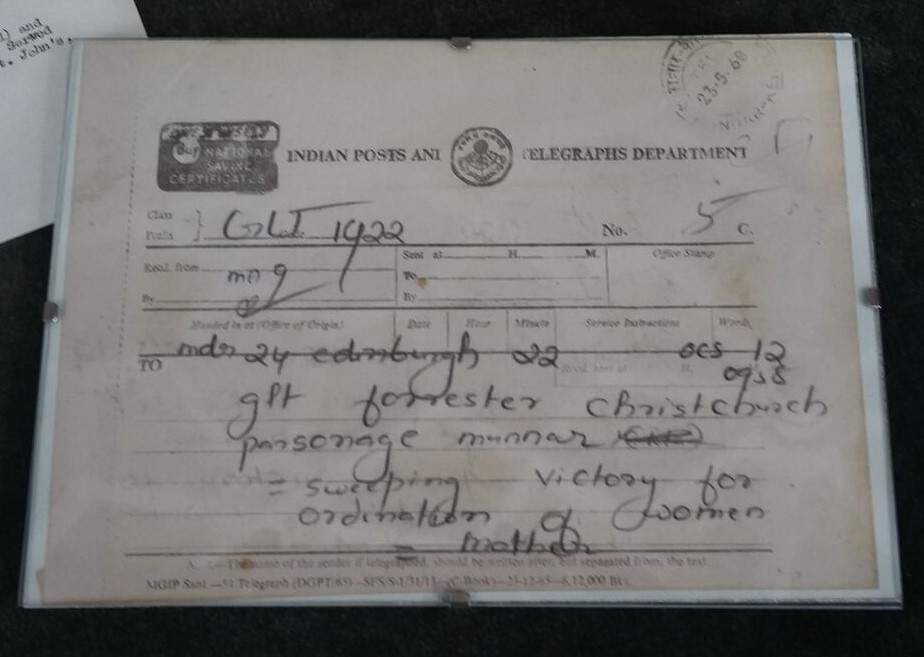

Finally, one year later, the historic decision was made that women could be called as ministers on the same terms as men. Isobel Forrester sent a cable to her son Duncan and his wife Margaret, working in India. It declared a ‘sweeping victory for women’s ordination’.

“A sweeping victory for the ordination of women” [1968]

Follow the link to watch this BBC Scotland programme which focuses on the 50th anniversary, including an extended interview with Rev Dr Margaret Forrester, and clips from the recent conference held here at New College. https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b0b4dvpv/general-assembly-2018-20052018

Dr Lesley Orr, Project Coordinator, School of Divinity