A guest post from Chloe Elder – New College Library Special Collections Digitisation Intern

Considering the ease with which most of us have access to information, it can be easy to forget the long way society has come in its efforts to provide resources for the public. For example, I’ve written this post on my very portable laptop in my Wi-Fi enabled flat and with my iPhone in constant peripheral vision. As we all know, before the days of the internet, our search for information required a trip to the library, but public libraries as we know them today did not exist before the middle of the nineteenth century. In the centuries preceding, the library has evolved from storehouses for records and archives, to ecclesiastical and academic cloisters, and the private collections of the elite and learned. And beginning in the late seventeenth century history, history saw a shift from the relative seclusion of these repositories toward a trend that supported the public dissemination of knowledge. One pioneer in this effort in Scotland was James Kirkwood, who is best known for his determination to provide Bibles to the parishes of the Scottish Highlands and for advocating for the establishment of parish libraries throughout Scotland in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

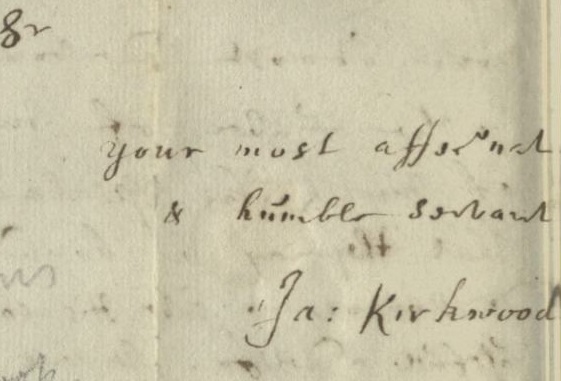

James Kirkwood’s signature. MSS KIR 3.1, New College Library

A graduate of the University of Edinburgh, James Kirkwood (c.1640-1708 or 1709) developed an interest for the Scottish Highlands and their parochial libraries during his early chaplaincy. Judging by the lack of printed editions of the Bible in Gaelic, Kirkwood noticed the need for appropriate translations to be distributed in the Highland areas. To pursue this goal, Kirkwood sought the assistance of Robert Boyle (1627-1691). Though better known as one of the fathers of modern chemistry, Boyle was also deeply invested in theology. Like Kirkwood, he thought that the Bible should be made available in the vernacular language of the people. Boyle personally sponsored the printing of the Old and New Testament in Gaelic, and in the 1680s Kirkwood pressed upon Boyle to allow more than 200 copies to be diverted to parishes in the Highlands.

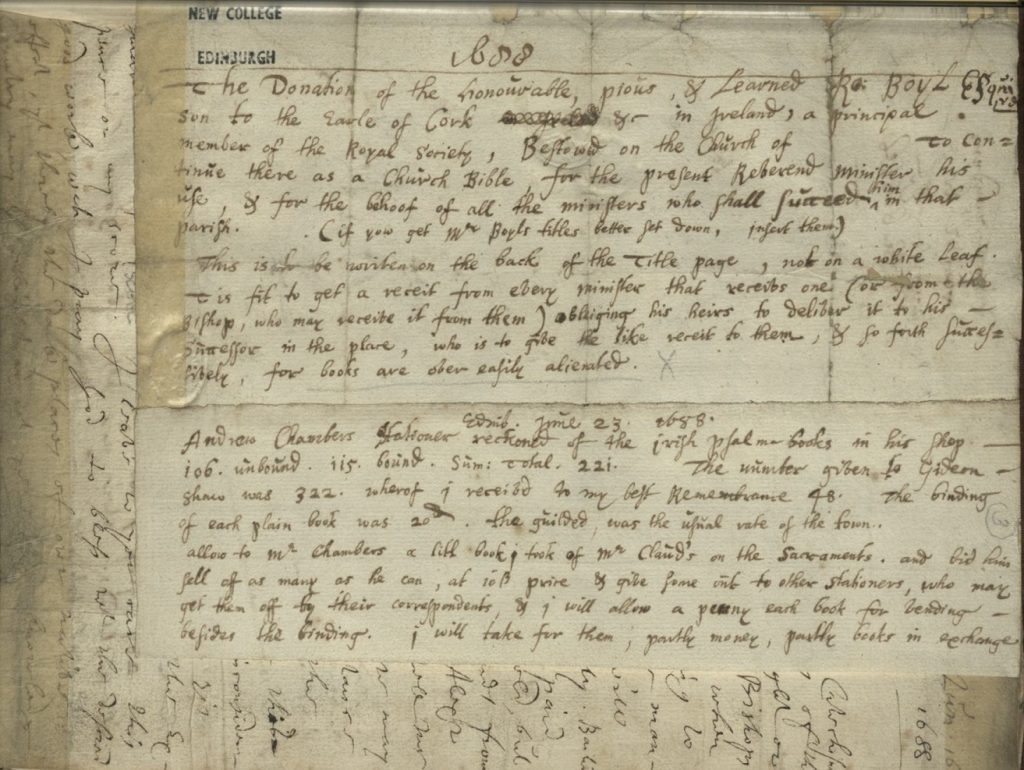

Letter from James Kirkwood referring to Robert Boyle’s support and saying : “It is fit to get a receipt from every minister that receives one … obliging his heirs to deliver it to his successor … for books are easily alienated.”

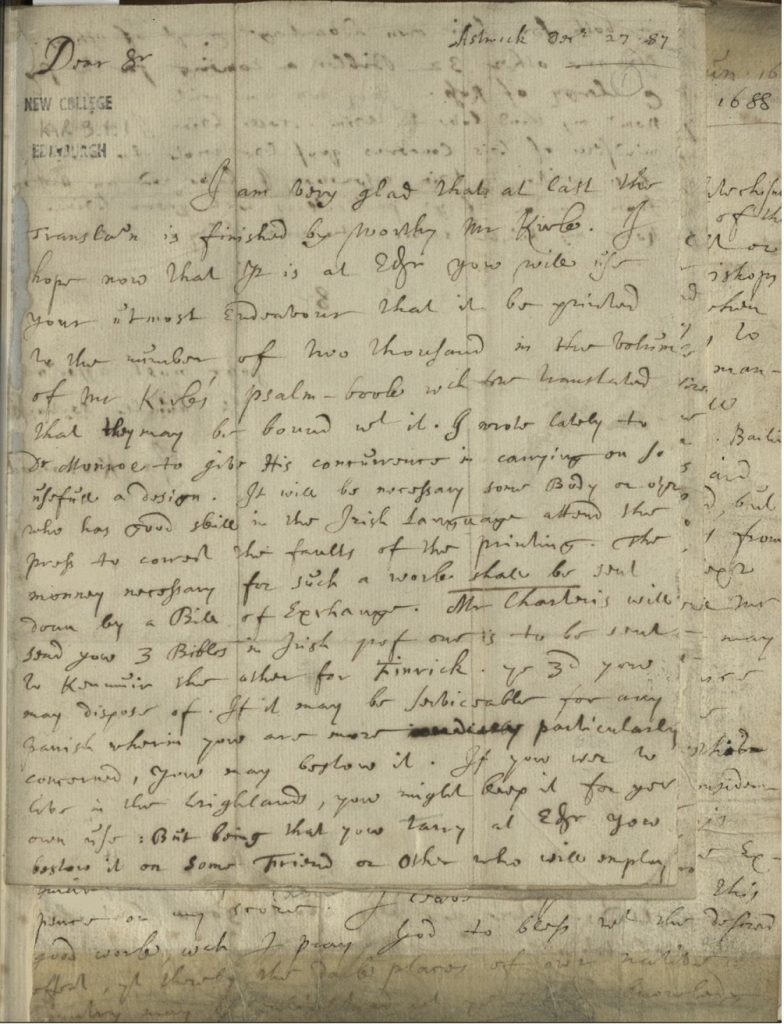

The newly-digitised Kirkwood Papers, a slim bound volume of manuscript letters, offers its readers a glimpse into the mind and business of James Kirkwood during this time. His correspondence details the project to colleagues and notes the receipt and distribution of copies to the parishes, listed across the sheets in sprawling handwriting. One can easily see, however, that it was a long and complicated process. For one, Boyle’s classical Gaelic translation differed from the spoken Scottish Gaelic. So, we can assume it is with relief that Kirkwood wrote in 1687 that he was “very glad that at last the translation is finished by worthy Mr Kirke.” Robert Kirke (1644-92) had provided Kirkwood with a new edition of the Bible (a venture again financed by Boyle), which conformed to Scottish usage and included a glossary of Scottish Gaelic terms. By the end of the decade, 1000 Bibles were distributed to Argyll alone, and hundreds more made their way to other parts of the highlands.

“I am very glad that at last the translation is finished by worthy Mr Kirke” – James Kirkwood

Kirkwood’s labours represent one of the challenges libraries and library supporters have faced throughout history. He wrote in 1688 that “books are often easily alienated,” and it is a fact that institutions are still grappling with today. Whether by distance, by language or by means, too often readers are separated from the resources they require. Digitisation technologies, however, are one way in which a library can remove these barriers and open up its stacks to both scholars and the general public alike. And as I scan the pages of Kirkwood’s letters into their new digital format, I can’t help but hope that my efforts, in some small way honour Kirkwood. After all, the underlying motivation behind both Kirkwood’s schemes and New College Library’s current project to digitize its Special Collections is to offer more accessible information to the public.

Chloe Elder – New College Library Special Collections Digitisation Intern