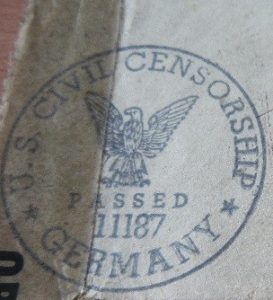

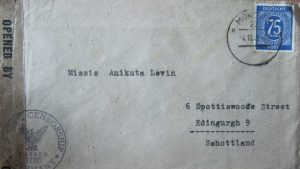

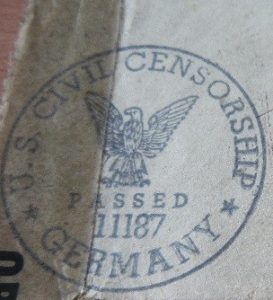

At the end of the Second World War, with the Nazi’s defeat, the three major allied powers entered Germany from different fronts. German civilians, especially women, were brutalised by the victorious allied forces: horrifying stories of the rapes which occurred across Berlin abound. The Russians liberated Berlin from the East, whilst the British moved through France. Munich, the Levins’ home prior to emigration, was a US occupied zone, as evidenced by the censorship stamps on the letters Anicuta received from an old friend Grete Vester. Grete was a photographer, and like Max Unold was part of the New Objectivity movement in German art (we have a photograph of Anicuta in the collection taken by Grete, referenced in correspondence). Germany entered a period of extreme economic devastation and hardship and the people suffered under the extreme war reparations which were claimed in compensation for the horror of the Holocaust. Trials were held across the country to punish ex-Nazi officials and purge Nazism from society: this process, as Grete writes, was called ‘Entnazifierung’ [de-nazification].

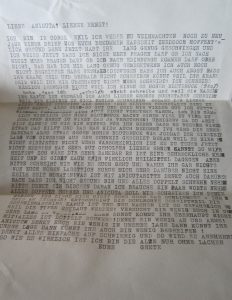

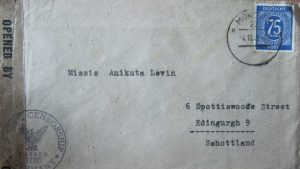

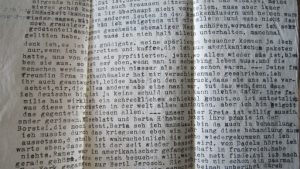

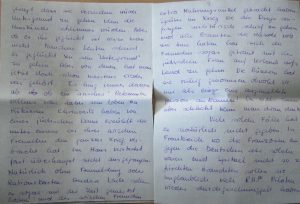

A series of letters from Grete Vester in Munich, with envelopes marked ‘American Zone’, and stamped with ‘U.S. Civil Censorship’ were sent to Anicuta Levin in Edinburgh between summer 1946 and 1947. These embittered letters from the Levins’ old friend show the extent of damage to war-torn Munich and the suffering of Germans in the extreme economic hardship of 1946 and 1947. Grete Vester, identified as one of the ‘old group’ of Munich friends in which Anicuta and Ernst socialised, is described by her sister Marla as having had three strokes throughout the course of the war.

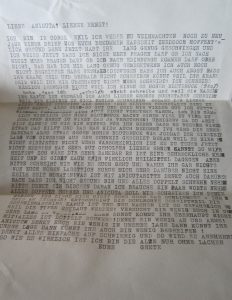

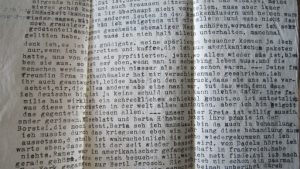

This series of letters touches on the major theme of German post-war identity – Grete expresses extreme anxieties around being deemed a Nazi by ex-neighbours and friends who had fled Germany due to persecution. She ardently claims that she was not a collaborator and in an angst-ridden tone bemoans the fate of German ‘innocents’. She describes post-war Germany as a ‘living hell’: the embittered people are murdering each other like savages. On several occasions, Grete expresses suicidal thoughts, reflecting the unbearably desolate circumstances in the ruins of central Europe circa. 1946/7.

****************************

4th April 1946:

“After six years of never-ending bad luck and abandonment, I am now writing to you full of hope and joy … in 1939 I had the bad luck to have a stroke and have been paralysed in my left side since then, although I can move again now, though with difficulty. In this state I spent the war, although I was evacuated to [Bad] Aibling. Now I am back in war-torn Munich, which you would barely recognise. Through the wretchedness, everywhere you look the people have become mean and embittered. The only thing I now long for is death. Kluger of course left me a long time ago, married a woman and had a child with her, though they are divorced already now. Obviously he already has someone else, because men always fare better in this matter”

“Oh, Anicuta, what did we live through! … I actually barely know what I should write, it cannot be expressed in words! … I would love to come and stay with you, and help with the housework”

(undated) April 1946:

“For God’s sake stay where you are! Don’t even consider trying to alleviate your homesickness for Germany! … I, a nazi-hater, as you know, should actually have a say in their [the Nazis] punishment! But the so-called ‘entnazifizierung’ [‘de-nazification’] is in someone else’s hands completely. Even us, the blameless, are suffering! I truly marvel at the fact that I didn’t end up in a concentration camp because of my big mouth [anti-Nazi discourse]. I guess that’s luck, or bad luck, however you might see it now”

16th August 1946:

“The letters which I so undeservedly receive from abroad are like balsam on my wounds … I was evacuated to Bad Aibling after a heavy attack on Munich … in the bomb shelter, everybody was drinking and flirting … they wanted to live their last hours with courage, or at least in the spirit of gallows humour … the basement doors flew open and the sounds of the bombs exploded in my ears and I waited for the end to come at any moment. But it passed, as you can see … When the Americans came, we were glad”

19th August 1946:

“I am constantly completely alone, at best Marla stops by with a cold face and the oft-used words “I don’t have much time, will need to leave in a few minutes””

[Writes that Marla tends to her out of a sense of duty, but there is no compassion or kindness behind it. Sadly she is reliant on her sister for vital supplies. Grete pleads with Anicuta not to mention her complaints in her reply as Marla reads through her letters.]

5th October 1946:

“I am living with complete strangers, not good or bad, just very uninteresting and also uninterested in me, we were just stuffed in here by the housing department, regardless of what you want. Otherwise you have to sleep in the street. The room is tiny, 2.5 – 4.5 metres, so I can’t put my few possessions anywhere … You cannot imagine what the city looks like now … I only get visitors when I have cigarettes and coffee from my American parcels”

[speaking of an old friend she has corresponded with] “Sadly I get the feeling that she holds us all in contempt, even me, who was anything but a Nazi. This hurts me as I cannot be to blame for being German, and cannot change this”

“The Unolds are somewhere in the countryside. Did you know Grete’s sister, Mrs Keis? She died and recently her son was murdered and robbed on a train. These things happen often these days. This is what desperation does. It doesn’t make people better. No one dares to walk the streets after dark, especially not women”

11th October 1946:

“I have been wanting to write to you about how I live, because I think this isn’t uninteresting to you. I think that all of you who left Germany, have no idea how it is here. Firstly, there is the devastation of the ‘luftkrieg’ [air raids], which is indescribable, although some people say that Munich is gold in comparison to some cities like Frankfurt [hit more intensely] … I need cod-liver oil and vitamin C. Of course you cannot get these in Germany, so I’ve written to New York and Switzerland and have received some already. We’ve had this appalling food for years and Hitler had been giving us low-quality food since 1933.”

“The atmosphere among the people is indescribable. It is as though one were among savages, no it is worse, since savages probably have naïve qualities that make them worthy of being alive … even the so-called ‘qualified’ people leave a lot to be desired. The whole of Germany has been completely ruined by the Nazireich”

[Asks Anicuta repeatedly not to be angry at her for requesting so many times that she join them in Scotland.]

2nd November 1946:

“As you can see, I am already writing on your new paper. Yesterday your package arrived. I tha nk you warmly and am so happy that at least this worry is alleviated. Sadly the package had been broken into and the typewriter ribbon was stolen out of it. But we are used to these things now … the ribbon clearly showed through the wrapping and someone decided to steal it. Here, people take everything. The people are so poor, that even an old cloth isn’t safe, if it can still be used to clean things with. Hitler left us a great country and through desperation, the people have not improved, but the opposite. This is the reason I can hardly bear it here anymore. Do you understand? … Even finding an envelope takes so long, because you have to go into many shops before you finally have the luck to find one or two”

nk you warmly and am so happy that at least this worry is alleviated. Sadly the package had been broken into and the typewriter ribbon was stolen out of it. But we are used to these things now … the ribbon clearly showed through the wrapping and someone decided to steal it. Here, people take everything. The people are so poor, that even an old cloth isn’t safe, if it can still be used to clean things with. Hitler left us a great country and through desperation, the people have not improved, but the opposite. This is the reason I can hardly bear it here anymore. Do you understand? … Even finding an envelope takes so long, because you have to go into many shops before you finally have the luck to find one or two”

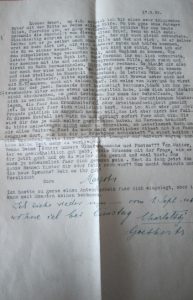

17th November 1946:

“today I have a big favour to ask you. In Edinburgh there is surely a phonebook for London, where you can find an address which I don’t have here. It’s the address of Dr Philip Hochschild, who emigrated there. He is a very wealthy man, and could I please ask you to write to him explaining my situation and asking him to help me a bit. I was often with him in the time of the Hitlerreich and so he knows, that I wasn’t a Nazi, which means he might be prepared to help me, considering my illness. From abroad, you can send a care-package through the Red Cross … [pleads Anicuta not to think worse of her because of this request] … we are starving and freezing. We don’t have access to the most basic amenities. Often we don’t have any light because the electricity goes. Then we also can’t cook anything, because we don’t have enough gas or fuel. We don’t even have any candles and not enough matches!”

26th December 1946:

“I received your long-awaited letter yesterday. It was truly the most wonderful Christmas gift. Hopefully it won’t just be a seasonal occurrence … letters are my only joy, and I receive them so rarely. So please don’t be so sparing! Remember than I am alone and lonely. Maybe then it will be easier for you to write more often”

“I am interested to see what we still have to live through, before life is over for us. Sometimes I think, I must have been a real piece of work in a past life, to have deserved such a punishment … no one laughs here anymore, at best cynically, which isn’t so nice”

“There are still Jew-haters here, Hitler really created long-lasting effects. It is awful. Us Germans are really suffering from this, even if one wasn’t a Nazi. And I think that won’t ever change, at least in my lifetime”

13th January 1947:

“My dear Anicuta, I thank you warmly for your last letter from the 18th December. I think I have already answered it, but am not completely sure, as I think of you almost all day long and therefore no longer know, whether I wrote to you or just meant to and thought of you intensely. I am alone for days on end. Marla often doesn’t come for a week, because as she says she has no time. And I sit here in my lonely room with hardly any wood to burn and a great sense of fear … Life is nightmarishly hard. I never dreamed that things would turn out this way. Maybe you can tell, that I don’t want to be alive anymore. But I am scared of death too. Do you understand this? There are also other things which I can’t write about. It would be such a joy if I could see you again … don’t be angry that I’m starting with all this again, because I really do think this would be the only thing that could save me now”

27th February 1947:

“You can hardly imagine what wretched lives we must lead now, even us, who were never Nazis! … You know, of course, what I thought [of the Nazi regime] and how I often opened my mouth to speak against them, even though I was spared the concentration camps. Even in Bad Aibling, where my hatred of the Nazis was well known! It seems disgraceful to have to re-iterate this to you, who knows all of this so well! But when one reads and hears how so many Nazis are trying to wash themselves clean [of their crimes], one thinks, perhaps even friends like you might believe this of me”

15th September 1947:

“I hardly dare to ask, if I couldn’t come to you [in Scotland], you seem to stall which makes me very unsure. Please don’t be offended, but just say yes or no. It is awful in Germany. You can only get medicine in very extreme cases, and life is horrible”

***********************************

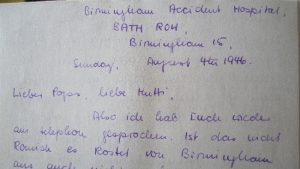

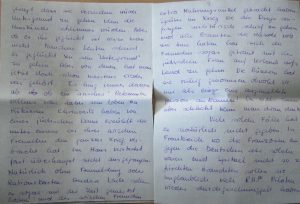

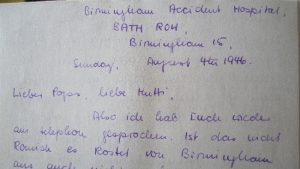

Letter from Annekathrin to her parents describing the fate of German loved ones

Annekathrin discusses the fate of those ‘missing persons’ who have not been heard from since the end of the war, including her Aunt Margot, who may have been sent to a German concentration camp in Riga, Latvia.

4th August, 1946

“There is no news about Aunt Margot. [Uncle] Kurt is still trying hard to receive any news of her through all manner of committees. Recently Kurt received a letter that Aunt Margot left with German friends before her deportation. The letter indicates that she knew exactly what was coming for her … she didn’t know what camp she would be sent to but assumed it would be Riga”

“Frieda Nauseu is also missing. She was in touch with Mrs Mitslaff, who told her that she would try to go underground if the circumstances worsened. But we don’t know if it worked. Apparently some people got lucky by going underground. But these people have usually come out of hiding by now. It always depended on whether or not an Aryan friend was ready to risk their life for you. I heard about a Jewish woman who was hidden by her Aryan friend for the whole war. She hid in the house and barely went outside. Of course without being registered, and with no ration card. Other people even noticed and brought extra food rations to the friend’s house. Later in the war when things started going wrong and all the officials had their hands full, the friend even risked going on holiday with the Jewish woman to the countryside! … one feels sick when one thinks about it”

“Of course, there weren’t many of these cases. In France, where many people were against the Germans … apparently they smuggled R.A.F. pilots out of the country. Uncle Kurt met one who was a friend of Lutz’s. He was shot down and the French farmers made sure he was treated quickly by a doctor and then they carried him through the village in a potato sack, and in a similar fashion took him to unoccupied territory, where he was quickly picked up by a plane and brought home”

“The letter from Grete is very moving. One really feels sorry for her. Hopefully her speech hasn’t also been affected by her paralysis. It seems as though it hasn’t been. Of course I understand that Pops is doing everything he can to bring her over here. This would probably be a very long process. But I also think it’s important to try. Her situation must be very hopeless. And she always ends up on the worst side. But it made me really happy to hear from her again”

*******************************

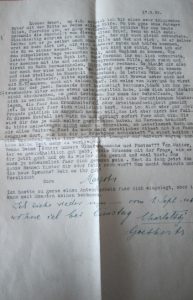

Letter from Margot Levin [later deported] to Ernst

In Annekathrin’s letter to her parents reflecting on the war, she mentions that Kurt Levin has still not found any trace of his and Ernst’s younger sister Margot. She had left a letter with German friends before being ‘deported’, but Annekathrin implies in an ominous tone that she was being sent to a camp in Riga, Latvia. This theory would be supported by the following letter, desperate in tone, sent to Ernst by Margot in the summer of 1939. Seven years later, with Annekathrin’s letter in 1946, the family still had not had any news from her. This could have been the last correspondence between Margot and her brothers, although there may be more letters in the collection yet to be discovered. Margot appears distressed at the progressively more dangerous situation for the Jewish community in Berlin, claiming that ‘most her circle has left’. She pleads with Ernst to find her any kind of work in the UK: coming over on a ‘domestic service visa’ was a common way to emigrate.

4th August 1939:

“I am currently writing to Kurt about all of my problems and urging him to help quickly. That is why I’m writing to you and ask you also to contact Kurt on my behalf. Hermann, who promised me help last year, has now left Ruth and I in the lurch and hardly ever replies to urgent letter, and if so then with a very late and short letter. This is hard to understand and very depressing for Ruth and I. So – I will have to help myself. I want to get out and ask you and Kurt to help me. I want to get a job there [in the UK], preferably in a family with children. So, I would be a nanny or companion … Please I urge you to look around for any work for me … maybe someone could take me into their household … I can write on a typewriter and do the unpleasant housework … It is very urgent to get a permit for [Britain]. Because the whole processing of the permit takes another 2 to 3 whole months. I’ve seen loads of our acquaintances go through the process. I’m one of the last of my circle to still be here [in Germany], and sadly lost a lot of time because of Hermann’s false promises. I am completely depressed … How is your wife [in the UK] and is she getting used to the new language? … What are the job prospects like there?”

17th August 1939:

“You have not answered my urgent letter and I fear it has gone missing so I am writing to you again … Kurt has only been in Britain for a short while and is therefore less able to help me than you surely are … Ruth told me that Hermann can no longer bring me out to her [in Israel] … So I have only one more option open to me: to come over to you and take a household position … Please talk to your colleagues and boss. I know (and you can check this at the Jewish association) that I am over the required house-help age [45] but don’t worry, it still works, just means that my employer will need insurance for injury at work or sudden inability to perform my duties”.

***********************************

Letter from Marla Vester in Munich to Anicuta in Edinburgh

A later letter from Grete Vester’s sister, Marla Vester, creates flaws in Grete’s bitter narrative, causing us to reconsider Grete’s psychological state in her painfully emotional desciptions of suffering. Marla explains that Grete is somewhat delusional, denying the occurrence of her second stroke. This is the last correspondence regarding Grete that I have uncovered in the collection.

4th May 1948:

“[Grete] has been in a bed in the psychiatric clinic’s neurological department for two months now, and the doctors recently told me that she cannot be healed and her situation is hopeless. It will only get worse. She can’t move anymore, the top half of her body looks very healthy and when you just see her top half lying in bed – if she isn’t crying which she does almost constantly now – she doesn’t look ill at all. But her legs are weak like a child’s and have no strength in them … it is awful, Anicuta, to see someone deteriorate like this and be unable to do anything … she suffers particularly acutely because she has lost her faith, and religion gives her absolutely no comfort anymore. She feels as though fate has been cruel to her, without believing that there is any fate beyond this earthly existence. The one good thing is that she is not in pain. / I visit her every Wednesday, but it’s very depressing because she always wants to go outside, which is impossible for her … two nurses have to carry her if she wants to lie outside / … Grete’s situation arose from a series of three strokes. The first one was on the 4th February 1939. She was in hospital for three months and then in a sanatorium for a further 2-3 months. She was left with her left arm and leg paralysed. But she could still walk with a walking stick … then she had a second,  less extreme stroke in the autumn of 1941 or 42. I don’t remember exactly anymore. [She has completely forgotten that this stroke ever happened and gets very angry if you mention it]. The paralysis became worse, and her nerves worsened, but then in May 1946 she had her last, heavy stroke which has left her in the present condition. The exact cause is not known. The doctor at the neurological station told me that she suffered at 40 years of age from the kind of stroke which usually hits people at 70. Sometimes I think, maybe some of the blame lies with her frequent sun-bathing. You might remember that for years, every time it was hot, she would lie out in the sun all day and would come home all dazed in the evenings”

less extreme stroke in the autumn of 1941 or 42. I don’t remember exactly anymore. [She has completely forgotten that this stroke ever happened and gets very angry if you mention it]. The paralysis became worse, and her nerves worsened, but then in May 1946 she had her last, heavy stroke which has left her in the present condition. The exact cause is not known. The doctor at the neurological station told me that she suffered at 40 years of age from the kind of stroke which usually hits people at 70. Sometimes I think, maybe some of the blame lies with her frequent sun-bathing. You might remember that for years, every time it was hot, she would lie out in the sun all day and would come home all dazed in the evenings”

If you know more about Grete or what happened to Margot Levin, we would love you to contact us. If you believe any content of this page infringes your rights, please see the Centre for Research Collections’ takedown policy.

nk you warmly and am so happy that at least this worry is alleviated. Sadly the package had been broken into and the typewriter ribbon was stolen out of it. But we are used to these things now … the ribbon clearly showed through the wrapping and someone decided to steal it. Here, people take everything. The people are so poor, that even an old cloth isn’t safe, if it can still be used to clean things with. Hitler left us a great country and through desperation, the people have not improved, but the opposite. This is the reason I can hardly bear it here anymore. Do you understand? … Even finding an envelope takes so long, because you have to go into many shops before you finally have the luck to find one or two”

nk you warmly and am so happy that at least this worry is alleviated. Sadly the package had been broken into and the typewriter ribbon was stolen out of it. But we are used to these things now … the ribbon clearly showed through the wrapping and someone decided to steal it. Here, people take everything. The people are so poor, that even an old cloth isn’t safe, if it can still be used to clean things with. Hitler left us a great country and through desperation, the people have not improved, but the opposite. This is the reason I can hardly bear it here anymore. Do you understand? … Even finding an envelope takes so long, because you have to go into many shops before you finally have the luck to find one or two”

less extreme stroke in the autumn of 1941 or 42. I don’t remember exactly anymore. [She has completely forgotten that this stroke ever happened and gets very angry if you mention it]. The paralysis became worse, and her nerves worsened, but then in May 1946 she had her last, heavy stroke which has left her in the present condition. The exact cause is not known. The doctor at the neurological station told me that she suffered at 40 years of age from the kind of stroke which usually hits people at 70. Sometimes I think, maybe some of the blame lies with her frequent sun-bathing. You might remember that for years, every time it was hot, she would lie out in the sun all day and would come home all dazed in the evenings”

less extreme stroke in the autumn of 1941 or 42. I don’t remember exactly anymore. [She has completely forgotten that this stroke ever happened and gets very angry if you mention it]. The paralysis became worse, and her nerves worsened, but then in May 1946 she had her last, heavy stroke which has left her in the present condition. The exact cause is not known. The doctor at the neurological station told me that she suffered at 40 years of age from the kind of stroke which usually hits people at 70. Sometimes I think, maybe some of the blame lies with her frequent sun-bathing. You might remember that for years, every time it was hot, she would lie out in the sun all day and would come home all dazed in the evenings”