Our Wellcome Trust funded project*, ‘Documenting the Understanding of Human Intelligence: cataloguing and preserving the papers of Professor Sir Godfrey Thomson’, is on course to deliver on all its objectives in the next few months. Continuing on from the cataloguing project, we aim to digitise Thomson’s papers, and catalogue related papers through the Moray House and University of Edinburgh collections. We will also be curating an exhibition regarding Thomson’s life and work in 2016.

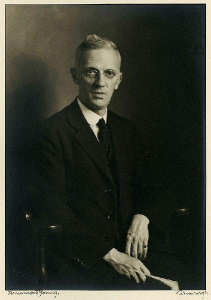

Professor Sir Godfrey Thomson (1881-1955)

To mark this exciting and continuing collaboration between the academic and archival communities, we are holding a free seminar for researchers, students, and archivists at Edinburgh University Library, 16th May 2014.

Professor Sir Godfrey Thomson (1881-1955) was a psychologist, statistician, and educator. The seminar programme reflects this, and is a varied one exploring Thomson’s work in Psychology (especially cognitive testing), Statistics, Education, and Eugenics, with academic speakers from each field. Chaired by Professor Dorothy Meill, Vice Principal and Head of the College of Humanities and Social Science, It will also discuss current scientific research facilitated through data sets left from Thomson’s work, as well as the complexities involved in interpreting and cataloguing the collection itself.

Professor Ian Deary’s British Academy Lecture on Thomson

Programme

Gathering Intelligence: the life and work of Professor Sir Godfrey Thomson

Chaired by Professor Dorothy Meill, Vice Principal and Head of the College of Humanities and Social Science

9. 15: Coffee and introduction

10.00: Martin Lawn, Senior Research Fellow, Department of Education, University of Oxford: ‘’His Great Institution’’: Thomson’s advanced school of education in Edinburgh’

10.30: Professor Ian Deary, Director, Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology: ‘Use of Thomson’s data today in studies of cognitive ageing and cognitive epidemiology’.

11.00: Tea and coffee

11.30: Professor Lindsay Paterson, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh: ‘Use of Thomson’s survey work in current research on social mobility and life-long education’

12.00: Dr Edmund Ramsden, ‘Thomson’s research and opinions on the differential birth rate and eugenics’.

12.30: Lunch (lunch is provided), and viewing of the collection

2.00: David Bartholomew, Professor Emeritus of Statistics at the London School of Economics: Thomson’s original statistical contributions

2.30: Emma Anthony, Project Archivist, Godfrey Thomson Project: ‘Interpreting and Cataloguing Thomson’s papers’

3.00: Panel discussion

4.00: Moray House tour

4.30: Finish

The seminar is free, but please note places must be booked through eventbrite.

Wellcome Trust bursaries for accommodation and travel are available.

For further information, contact Emma.Anthony@ed.ac.uk.

*Funded by the Trust’s Research Resources grant scheme under the call ‘Understanding the Human Brain’. Continuing on from the current cataloguing project, we aim to digitise Thomson’s papers, and catalogue related papers through the Moray House and University of Edinburgh collections. We will also be curating an exhibition regarding Thomson’s life and work in 2016.