Behind every great man is that truly awful platitude reserved for the woman in his shadow! Researchers and archivists often despair about the absence of women – and not only women, but that’s several other blogs! – found in the margins of the papers of great men. What was their part in the story, other than that of a dutiful wife neglected in the pursuit of greatness?

Comparatively little is known about Thomson’s wife, Jennie (or to give her full title, Lady Thomson!). She is admittedly rather absent from his autobiography, The Education of an Englishman. This may be pardonable in some respects as it is largely about his education and career, though indeed one might say what is marriage if not an education?! Thomson tells us that he married his ‘younger colleague’ and settled down to ‘happiness and careful budgeting’. We know they met at Armstrong College, where Jenny was also teaching, and that they had one child, Hector. We know that Thomson’s many influential friends, including Carlos Paton Blacker, thought very highly of Jennie and enjoyed her company – but why? Was she witty? Good humoured? Or did she simply bake a mean scone as the annotations to Thomson’s recipe book would attest?!

Thomson credited Jennie for winning the Urban Prize with him, saying that she carried out the mathematical calculations, but Jennie’s story is somewhat different:

One night, sitting as usual in his study with Crelle’s Rechaud Tafel on my knee I said to him ‘You know Godfrey, although I can do these calculations, I haven’t the faintest idea of what it is really all about.

He said ’Never mind, dear, I didn’t want a competitor, only a wife!’

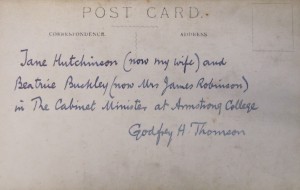

However, from Thomson’s papers it is entirely clear just how much his Jennie meant to him, and how much her Godfrey meant to her. Its telling, for instance, that Thomson kept so many photographs of Jennie, that on one of the photographs of her in full costume for an amateur production at Durham University, Thomson has written ‘Jane Hutchinson, (now my wife), in what I like to imagine was a proud and steady hand!

We can see Jennie in the papers of James Fitzjames Duff, in a letter from Thomson’s friend, G R Goldsborough, who recalls how Thomson informed him of his marriage:

I wrote back a congratulatory letter saying how fortunate she was to have a man of such fine qualities; which I was sure would lead to a happy union and future prosperity. He immediately replied saying that it would please him very much if I would write and say the same to Jennie! I felt it a pecuiliar request, but I did as he asked and got what I deserved for my pains – a cool reply with a plain hint that such an unsolicited testimonial was not required.

Jennie clearly knew that Thomson, for all his ‘fine qualities’, was jolly lucky to have her!

Nowhere is the love between Thomson and Jennie more apparent than her biographical notes. Thomson died 14 years before Lady Thomson. Sadly, Jennie never finished the biography, perhaps because she suffered from poor health following Thomson’s death until her own. However, the notes she left behind give an insight into the man she knew better than anyone. She describes Thomson’s characteristics – his humour, his kindness, his egalitarian nature:

He possessed a strong sense of humour, a ready wit and considerate personal charm which made him a perfect host at his own table. His tasks were simple, he loved his fellow men…He had what all great people had – humility.

Lady Thomson’s notes regarding Thomson’s death are particularly poignant:

I have said earlier that Godfrey sought truth and was not afraid of it when he met it. He was not afraid when he met it at the last.

He asked me two days before he died if the doctors had told me he was going to die. He said “I am not afraid to die, but I am afraid of the pain and anguish to you”.

Through my barely hidden tears, I said “Yes dear, I know you are very ill, but I am your old sweetheart you know – and I am coming to you soon”. He said “Some things are certainties”

Thomson died in the afternoon of the following day. Jennie, or Lady Thomson as she was by then, was flooded with letters of sympathy telling her how much the sender admired and loved Thomson, from many of the world’s leading statisticians and psychometricians including Charles Paton Blacker and David Glass, as well as several letters from past students. Almost every letter states Jennie should not answer, she should rest, etc., and almost every letter is marked ‘answered’, with the date Jennie replied.

We will likely never know terribly much about Jennie other than the traces dotted around Thomson’s papers – the photographs of her, the book about Durham she gave him for Christmas 1914 – but Thomson treasured these traces. He referred to them throughout his life, often annotating them in hindsight. Jennie wasn’t ‘just’ a wife to Thomson, and she wasn’t ‘just’ a figure in the background of his achievements. She was his partner, his friend, and the person he trusted the most, and he was all those things to her.