According to researchers at the Centre for Research Collections, The Indian Primer is a tiny book containing Christian instruction, mainly in the native American Algonquian language. Printing began in America in 1640 and was used by missionary John Eliot, who translated the Bible and many other works into the native language for the first time. This unique 1669 copy was gifted to the University Library in 1675 by James Kirkton. Amazingly, this copy is still in its original American binding, of decorated white animal skin over thin wooden boards.

Stories beget stories – it’s one of my favourite things about them – and archives are built on precisely this strength. Archival collections, like those at the University of Edinburgh, do not simply store and preserve artefacts, but actually become a medium through which stories, both existing and those yet to be told, can find a voice. As these musings might already indicate, I’ve been recently reminded of the centrality of stories to archives through my time as a volunteer in the Digital Imaging Unit working on various papers related to Rachel Erskine, née Chiesley (bap.1679-1745), or, as she is more infamously known, Lady Grange.

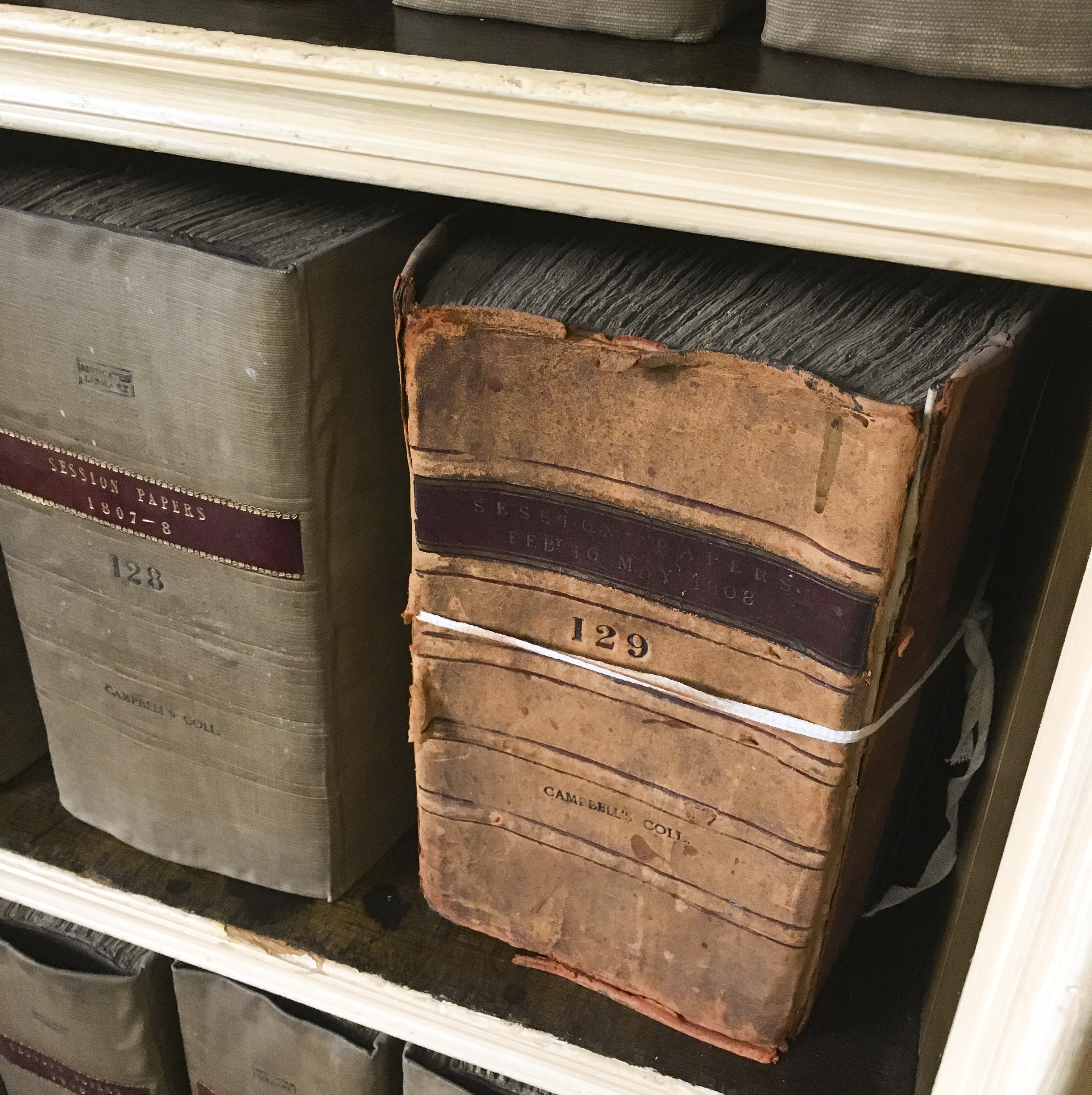

Stories beget stories – it’s one of my favourite things about them – and archives are built on precisely this strength. Archival collections, like those at the University of Edinburgh, do not simply store and preserve artefacts, but actually become a medium through which stories, both existing and those yet to be told, can find a voice. As these musings might already indicate, I’ve been recently reminded of the centrality of stories to archives through my time as a volunteer in the Digital Imaging Unit working on various papers related to Rachel Erskine, née Chiesley (bap.1679-1745), or, as she is more infamously known, Lady Grange. At present I am working on a pilot project, digitising the Scottish Court of Session Papers. The collection is held across three institutions; The Advocate’s Library, The Signet Library and the University of Edinburgh’s Library and University Collections. The collection itself consists of circa 6500 volumes, comprising court cases which span the 18th and 19th century.

At present I am working on a pilot project, digitising the Scottish Court of Session Papers. The collection is held across three institutions; The Advocate’s Library, The Signet Library and the University of Edinburgh’s Library and University Collections. The collection itself consists of circa 6500 volumes, comprising court cases which span the 18th and 19th century.