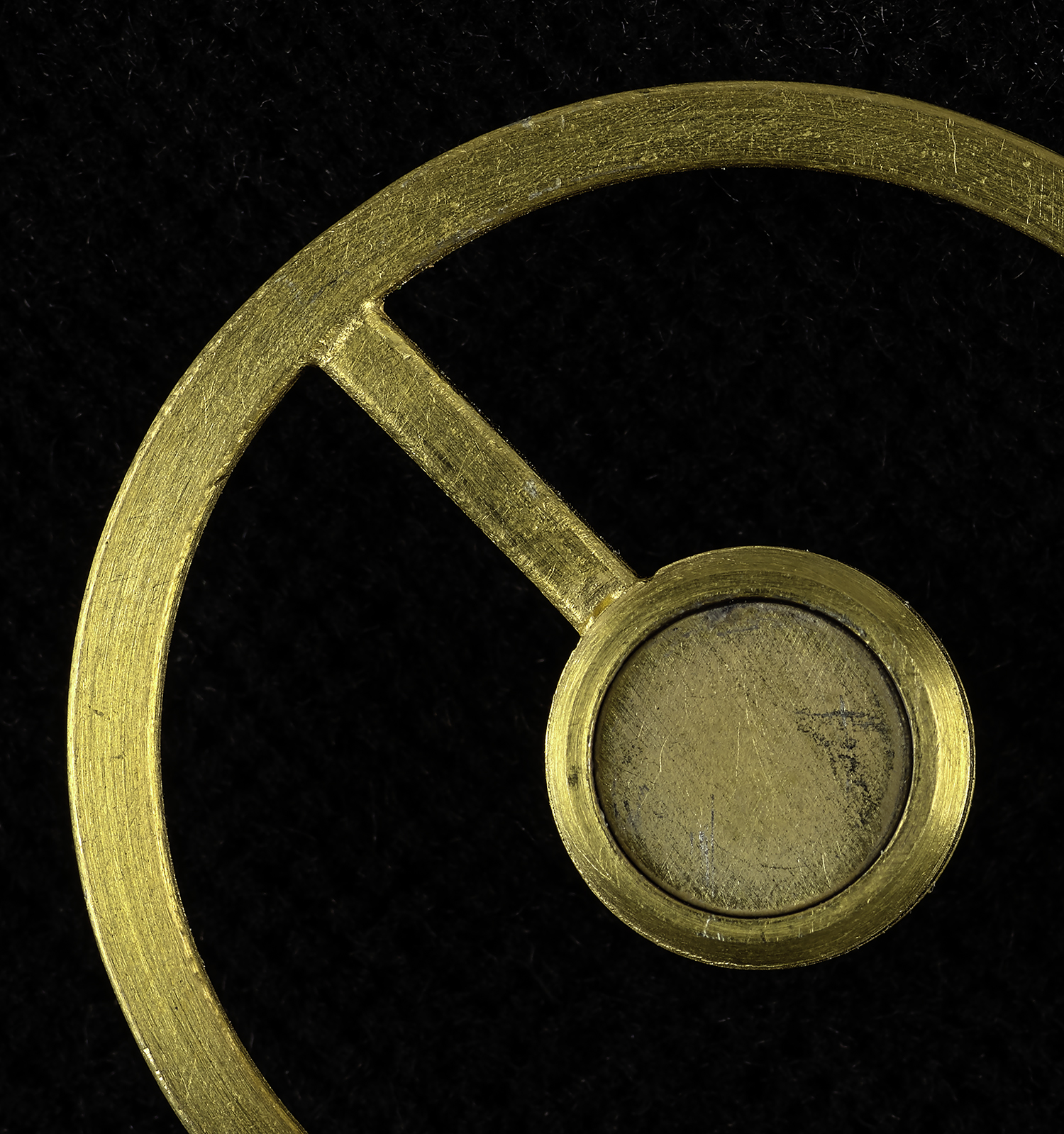

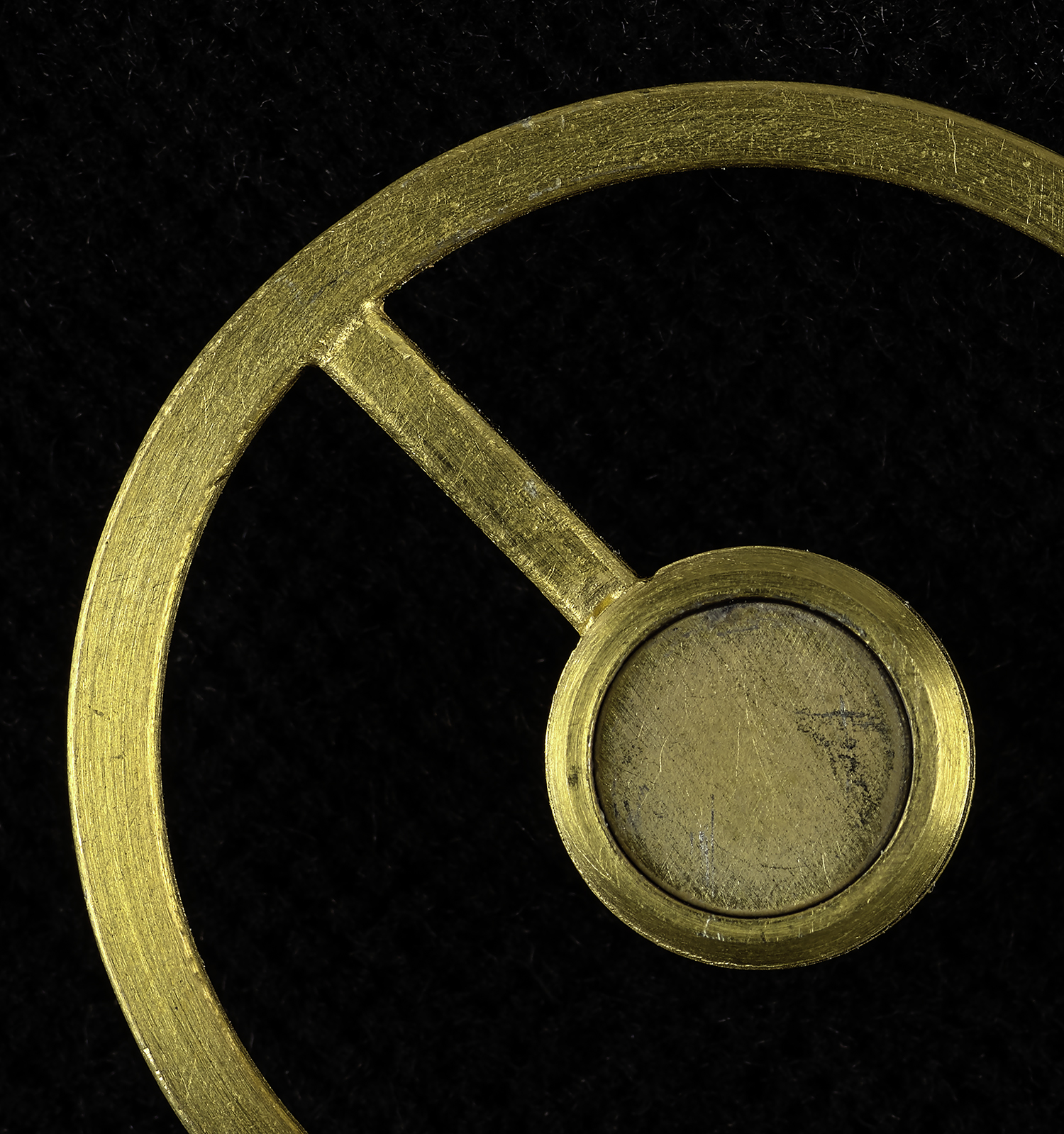

The Art Collection acquired one piece from Dong Ding’s sculptural jewellery collection Boundary of Balance; a series of works which explores the relationship and tension between balance and imbalance. Each of the carefully crafted kinetic pieces can be worn in multiple ways – disassembled and re-assembled by the wearer – with interchangeable and detachable details such as rings, tie pins and earrings integrated into the overall composition.

The movement of each piece is influenced by these counterbalanced components, as well as by the body and actions of the wearer. Sharing a passing resemblance to historical navigational tools, the works come accompanied with bespoke laser cut instructions identifying the multiple permutations for the wearer. Julie-Ann Delaney Art Collections Curator University of Edinburgh.

“A piece may contain hidden details and contrasting elements of weight and material. The work is kinetic with moveable parts that invite play. Movement is influenced by counterbalanced components, interchangeable parts and the wearer’s body movement. Through interaction with the work, the wearer is invited to play with the tension between balance and imbalance.” Dong Ding.

Museum Collections Manager Anna Hawkins outlined the photography and handling of the complex object. Multiple images were required to accurately record the condition of the piece at point of entry into the Museum Collections. This included two views of the whole object back and front and in addition back and front views of each individual part of the object in isolation.

To achieve a detailed representation I employed focus stacking to achieve the consistent detail. This involves taking multiple images at different focal lengths and aligning these images to create one image with overall focus. Below is a selection of some of the images captured. I have included partial details to demonstrate the capabilities of our medium format cameras. The resulting Tiff files are delivered to the Museum Collections team in excess of 100Mb which can be used for condition checking and allowing detailed object examination. These images are also suitable for publication, broadcast and social media.