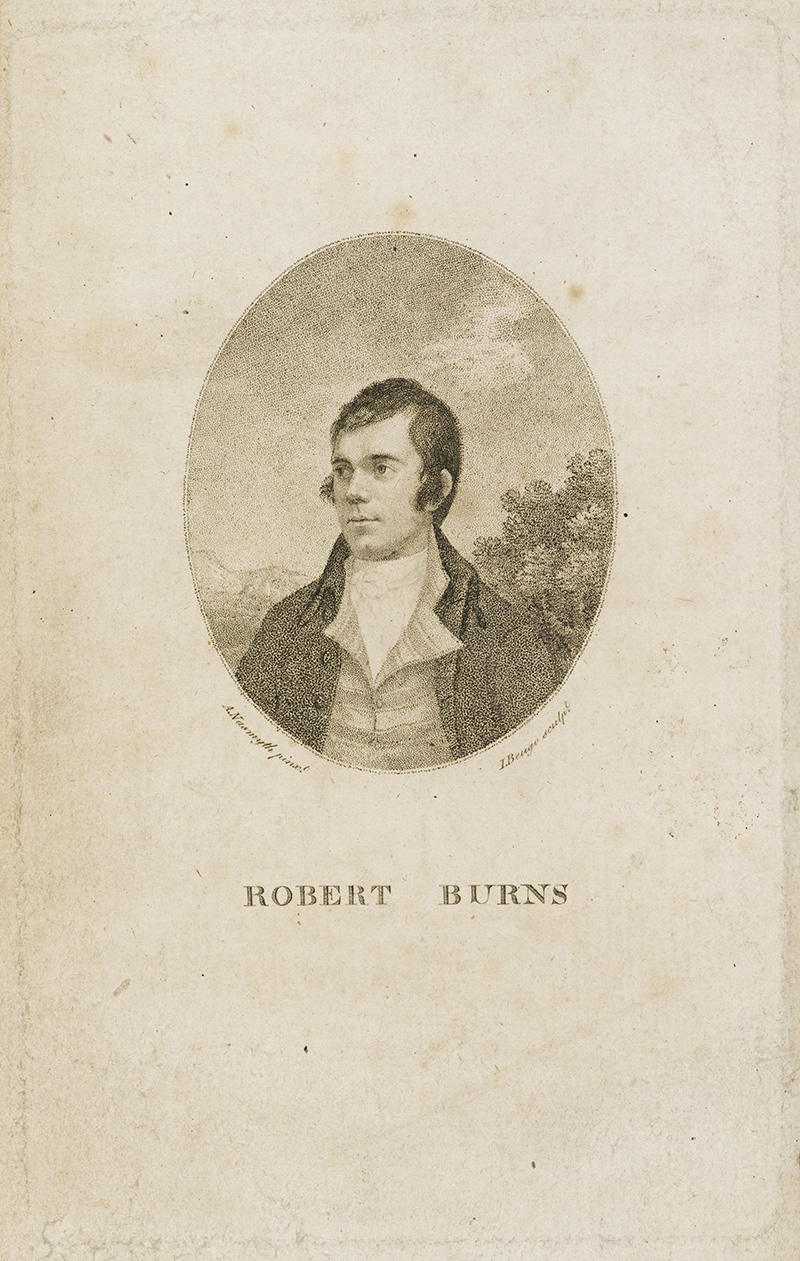

It’s the time of year for all things Robert Burns. Here in the DIU I have recently finished digitising a collection of Robert Burns Manuscripts. These are highly treasured manuscripts which make up part of our Iconics Collection. A fitting status for the bard himself. So, time raise a glass! The manuscripts comprise of letters of correspondence and poems such as Holy Willie’s Prayer, Love and Liberty: A Cantata and Address to Edinburgh.

Category: <span>School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures</span>

According to researchers at the Centre for Research Collections, The Indian Primer is a tiny book containing Christian instruction, mainly in the native American Algonquian language. Printing began in America in 1640 and was used by missionary John Eliot, who translated the Bible and many other works into the native language for the first time. This unique 1669 copy was gifted to the University Library in 1675 by James Kirkton. Amazingly, this copy is still in its original American binding, of decorated white animal skin over thin wooden boards.

In this weeks’ blog post we are pleased to welcome our newest member of staff, Juliette Lichman. When not working on new orders, she has been preparing old ones to go into our Open Books Repository https://openbooks.is.ed.ac.uk/ Juliette has been discovering how easy it is to get drawn in to the complex and fascinating histories of the books…

In this weeks’ blog post we are pleased to welcome our newest member of staff, Juliette Lichman. When not working on new orders, she has been preparing old ones to go into our Open Books Repository https://openbooks.is.ed.ac.uk/ Juliette has been discovering how easy it is to get drawn in to the complex and fascinating histories of the books…

The university’s cherished Laing collection is an invaluable resource of important historical documents, and is a frequent subject on this blog. The fact that there are still so many unknown works and exciting discoveries to be made within the collection is astounding. I was lucky enough to experience this first-hand several weeks ago, during an afternoon of working through a deeply buried folder of book scans. I came across a Laing collection document that had incorrect and missing metadata. It appeared to be an unassuming manuscript (date unknown) with handwriting that was ornately scribed but difficult to decipher, though certainly English.

Following on from a visit from the Confucius Institute in September, it was agreed we should digitize our volume of photographs from Lord Elgin’s 1860 military campaign in China. Our…

The most important manuscript collection at the University of Edinburgh has long been acknowledged to be the Laing Collection. This treasure trove was donated to the University of Edinburgh in 1878 by David Laing (1793-1878) and contains a startlingly vast array of texts and artefacts. To gloss this diversity only briefly, the University’s description of the Laing collection attests that one can find more than 100 Western medieval manuscript books, a 9th-century Koran, over 3000 charters, manuscript poems, texts, and letters written by Robert Burns (1759-1796), the lovely illustrated “Album Amicorum” (book of friends) by Michael Van Meer (?-1653), and poetry by Elizabeth Melville (1582-1640). Even the handlist for the collection is itself an archival artefact of sorts, having been drawn up in 1878 at the time of the bequest and bearing traces of additions and corrections made over the years since.

As important as the Laing collection is though, I’ll admit that until a couple of months ago, I didn’t know much about it and I certainly hadn’t spent any time delving into what it has to offer. I’m an English literature PhD here at the University of Edinburgh and my research focuses on archives, digital humanities, and, in particular, the study of idiosyncratic texts, like concrete poetry and scrapbooks. I like that these works challenge traditional literary classifications and give some pause when users must decide how to read them, digitise them, or otherwise interpret them. These interests led me to volunteer with the DIU, where I have been working to enrich the descriptive metadata of digitised items from the University’s Special Collections and Library holdings. This is also what finally led me to the Laing collection.

Recently Art Collections Curator, Neil Lebeter, and I made a short video interview with Professor Bob Fisher and Phd student Alex Davies of the Informatics Department. Bob and Alex have been working with the images I produced of the Eduardo Paolozzi mosaics within the DIU (for an introduction to the project click here). This cross departmental work seems particularly fitting as Paolozzi had close ties to the Informatics department. This relationship is visible in the form of several Paolozzi sculptures dotted about the Informatics building.

Using their combined expertise, Bob and Alex have been employing a number of image processing techniques on the images of the individual mosaic fragments in line with images of the original mural design, in situ at Tottenham Court Road Tube Station, London. This is to assess what percentage of the original mural we possess and how accurately it could potentially be pieced back together. The interview provides an insight into their work processes, the challenges, and uniqueness, of this particular project and the results they have found to date. It is an interesting watch!

With the 400th anniversary this year of the death of one of our greatest and most influential playwrights, William Shakespeare, I found myself cropping images of some of his first printed quartos for the creation of an e-reader as part of the Shakespeare image collection. Now existing as high quality e-readers are the plays Love’s Labours Lost (1st Quarto Edition) and Romeo and Juliet (2nd Quarto Edition), both of which are used as part of the collaborative project concerning Shakespeare’s printed quartos, The Shakespeare Quarto Archive (http://www.quartos.org/index.html). These works themselves have very unique histories and are important in Shakespearean studies for many reasons. Their place in the Special Collections in the University of Edinburgh Library is invaluable.

With the 400th anniversary this year of the death of one of our greatest and most influential playwrights, William Shakespeare, I found myself cropping images of some of his first printed quartos for the creation of an e-reader as part of the Shakespeare image collection. Now existing as high quality e-readers are the plays Love’s Labours Lost (1st Quarto Edition) and Romeo and Juliet (2nd Quarto Edition), both of which are used as part of the collaborative project concerning Shakespeare’s printed quartos, The Shakespeare Quarto Archive (http://www.quartos.org/index.html). These works themselves have very unique histories and are important in Shakespearean studies for many reasons. Their place in the Special Collections in the University of Edinburgh Library is invaluable.

Recently I was asked to scope the digitisation of a beautiful scroll we have in our collection, Or.Ms 510, or better known as the Mahabharata. Gemma Scott, our former Digital Library intern, says that:

‘the Mahabharata tells the tale of a dynastic struggle between two sets of cousins for control of the Bharata kingdom in central India. One of the longest poems ever written, eclipsed only by the Gesar Epic of Tibet, it is said to have been composed between 900 and 400BCE by the sage Vyasa, although, in reality, it is likely to have been created by a number of individuals. To Hindus, it is important in terms of both dharma (moral law) and history (itihasa), as its themes are often didactic.’

Our scroll dates to 1795 and came to Edinburgh University in 1821 when it was donated by Colonel Walker of Bowland. It is 13.5cm wide and a staggering 72m long, housed in a wooden case, wound around rollers and turned by a key in the side. It has 78 miniatures of varying sizes and is elaborately decorated in gold, with floral patterning in the late Mughul or Kangra style. The text itself is dense, tiny, and underpinned with yet more gold leaf decorations.

We are thrilled to announce that we now have online the entire manuscript of Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni, his ‘Chronology of Ancient Nations’. Al- Biruni was a famous astronomer and polymath and he completed this compendium in the year 1000. It records a vast number of calendars and chronological systems from a variety of different cultural and religious groups in the late antique and medieval periods in the Hellenic world, Central Asia and the Near East, even detailing festivals and liturgical practices.

One of the works in the ECA Rare Book Collection that places us firmly in a place and time in history is a book of photographs taken around the time of the notable expedition of Lord Elgin, James Bruce, to China on a diplomatic mission and military campaign. If one does not know much about Chinese history, which I must admit I know little of, you might view this image at first glance as simply another beautiful view of Chinese landscape and architecture. Upon further reading into the life of the 8th Earl of Elgin and the Old Summer Palace, as well as the photographers whose works are featured in the album, it becomes a much different story. One of these photographers was the talented Felice Beato who was known for photography that created images of war as a continuous process. He documented each stage of his subjects, including gruesome scenes of the aftermath of battles and seizes. This method provides great insight into the progression of Lord Elgin’s presence in China as many images fit into his timeline. Although the above photograph taken in 1860 seems to show a sturdy structure overlooking a stunning mountain range, it does depict a cultural landscape that was near the end of its time and one that was extremely vulnerable at the time. The caption for the image tells a snapshot of the gruesome story. The caption reads “View of the Summer Palace, Yuen-Min-Yuen, showing the Pagoda before the burning, Pekin. Octr 1860.” This could easily be one of the last photographs of the site before its infamous looting and burning on October 18, 1860. Many of the items taken from this event are still held today in the UK and other prestigious museums in Europe, although there is an ongoing conversation of where these works of great art and cultural importance belong.