Have you ever been stuck for a good nursery rhyme to tell your kids? Or needed a cure for a headache that just will not go away? Or perhaps you’ve found yourself wondering – what is the best way to protect my butter from being cursed by witches? If the answer to any of these questions is yes (or possibly “why would a witch curse my butter?”) then let me introduce you to the collection recently digitised by our Cultural Heritage Digitisation Service team that can answer all these questions and more – the Maclagan Manuscripts.

About the Collection

As part of the School of Scottish Studies Archives’ special collections, the Maclagan Manuscripts are believed to be one of the most significant written collections of 19th century Scottish folklore.

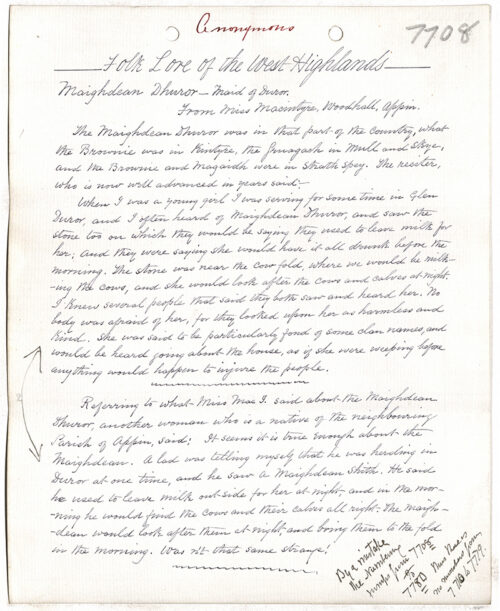

In 1889 during the annual meeting of the Folklore Society in London, a call was made to its members to collect items of folkloric interest from across the United Kingdom (University of Edinburgh, 2021). Among these members was Doctor Robert Craig Maclagan (1838 – 1919), an Edinburgh-based doctor with a passionate interest in folklore. Inspired by this call, Dr Maclagan would go on to spearhead what became an almost ten-year long project to collect first-hand accounts of folklore from across Scotland – some of which became the foundation for much of his own later published work.

From 1893 – 1902 Maclagan, along with a dedicated team of Gaelic-speakers, were able to collect an incredible amount of diverse material in both English and Gaelic (which was still the main language spoken in many places across the West Highlands during the 19th century) (MacKinnon, K, 1988).

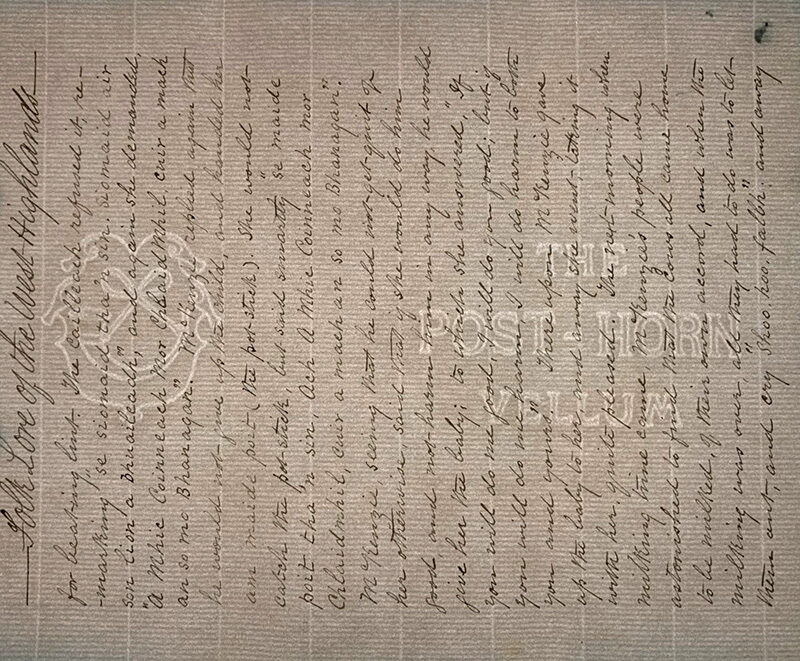

The impressive variety of topics covered by the Maclagan Manuscripts is what makes this collection one of the most valuable and unique resources for the study of 19th century folklore in Scotland. There are over 9000 individual pages of handwritten notes covering all sorts of things from everyday practices like material culture, songs, dyeing recipes for fabric and children’s games and puzzles, through to folk medicine, ghost stories and even ways to protect against witchcraft. Unfortunately, up till now its sheer size has also made it difficult for people to explore and use this collection to its fullest potential.

Digitising the Manuscripts

To help improve accessibility to this collection, myself and Charlotte Swindell, the other Digitisation Operator from the Cultural Heritage Digitisation Service team have been working since March to digitise these manuscripts and upload them online for open access. With thousands of pages to digitise though, this is one of the largest projects I have been involved in since starting here!

Thankfully despite the huge volume of material, this collection is mostly made up of single sheets of paper that are all in pretty good condition. As a result, we’ve been able to digitise this whole collection just using our Bookeye 4 overhead scanner (if you want to learn more about how we use our overhead scanners, why not go check out our post on digitising the LHSA’s HIV & AIDS collection here). This has been allowing us to digitise the collection efficiently as we can quickly produce good quality images of the manuscripts with this type of scanning equipment, without putting unnecessary stress on the originals that could risk damaging them.

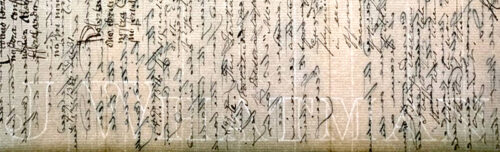

While working on this project I’ve been coming across lots of interesting things, including some fascinating watermarks and evidence of paper-making techniques from this period. So far, within this collection we’ve found two very distinct watermarks indicating that two different brands of paper were used by Maclagan’s team over the course of this ten-year project. We can see these watermarks more clearly by shining a light through the paper (also known as viewing with transmitted light).

In this case we achieved this by using a light sheet. Light sheets work in pretty much the same way as a light box for creating transmitted light but are a lot thinner (only a bit thicker than a sheet of paper) so that they can also be slipped in between pages, particularly in bound volumes.

This makes it much easier for us to look for things like watermarks, especially when dealing with more complex or fragile objects, while reducing the amount of potentially damaging handling that could be involved otherwise to get similar results.

Finding watermarks like these are a common occurrence when digitising older paper-based collections like the Maclagan Manuscripts as they were regularly used by paper makers as early forms of trademarks or logos for their products (Murphy, 2021). And, because they would continuously evolve and change over years, watermarks not only have historical, artistic, and cultural significance, but can also provide interesting contextual evidence about the paper-making industry at the time certain batches of paper were made (Müller, 2021).

Alongside the watermarks, looking at the Maclagan Manuscripts using transmitted light can also tell us how the paper itself was actually made. Both types of paper found in this collection are examples of ’laid’ paper –identifiable by those lines you can see running through the structure of the sheets. These lines, known as chain lines, are formed during the manufacturing process by dipping a wire sieve attached to a rectangular mould into a vat of diluted cellulose fibre pulp (Müller, 2021). Once the water was drained out between the wires of the sieve, the moulds were shaken to lock the paper fibres together to make the sheets (Müller, 2021). As a result, the pattern of wires from the sieve are then imprinted into the newly formed sheets of paper, causing those characteristic lines and if you want to see what this looks like, you can watch a video demonstrating the process of hand-making paper here.

Laid paper was the sole paper manufacturing technique for all paper up until the invention of higher quality woven paper in the 1750’s by the J. Whatman paper mills in Kent (Vintage Paper Co., 2019; Hunter, 1943). However, at the time this was still extremely expensive to produce. As a result, laid paper remained the dominant type of paper commercially available right up until the development of industrialised paper-making techniques in the 19th century, which then made wove paper much more affordable (Hunter, 1943).

The high quality of the paper that Maclagan used to document the culture and traditions of the West Highlands was potentially chosen as a means of recognising the importance and value of the cultural material that was being collected. We’ve seen evidence of this with other similar collections created at the same as the Maclagan Manuscripts, including Alexander Carmichael’s Carmina Gadelica, a six-volume compendium of 19th century Scottish Gaelic customs, beliefs, traditions and folklore. It is thought that Alexander Carmichael had this compendium published intentionally as a beautifully illustrated luxury volume to better reflect the significant cultural value of its contents (Stiùbhart, 2019).

It is possible that Dr Maclagan and his team similarly believed that such valuable information should be recorded using high quality materials. It’s fascinating that alongside the rich depth of knowledge about Scottish folklore and culture contained within the Maclagan Manuscripts, the materials used by Maclagan and his team to record these accounts can themselves provide insights that we can use to view this unique collection within a much wider historical and social context.

Digitising such a unique and interesting body of material has been a great experience and I am looking forward to seeing what else people will be able to learn from this collection in the future now that it is more widely accessible online!

Our Progress So Far

So far, we have digitised the entire Maclagan Manuscripts collection, the majority of which you can find and download for free on the University of Edinburgh’s Open Books online repository here!

This project is still on-going though as there are still some manuscripts left to go up online, but we will keep you updated on its progress here on this blog – so stay tuned for more updates!

By Gaby Cortés, Digitisation Operator

Sources

How It’s Made, ‘Handmade Paper – How It’s Made’, Discovery UK, (2019) Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cyU5Bb8jd1s

Hunter, D., Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, Dover Publications, (1943).

MacKinnon, K., ‘A Century on the Census: Gaelic in Twentieth Century Focus’, Gaelic and Scots in Harmony, Thomson, D.S (ed.), (1988). Source: https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/critical/aboutus/resources/stella/projects/starn/language/gaelic-and-scots-in-harmony/a-century-on-the-census/

Müller, L., ‘Understanding Paper: Structures, Watermarks, and a Conservator’s Passion’, Harvard Art Museums, (2021) Source: https://harvardartmuseums.org/article/understanding-paper-structures-watermarks-and-a-conservator-s-passion

Murphy, H., ‘The Imagery of Early Watermarks’, Qatar Digital Library, (2021) Source: https://www.qdl.qa/en/imagery-early-watermarks

Stiùbhart, D.U., ‘The Theology of Carmina Gadelica’, The History of Scottish Theology Volume III: The Long Twentieth Century, Fergusson, D., Elliott, M. (Eds.), Oxford University Press, Oxford, (2019), pp.1-17

The University of Edinburgh Information Services, ‘The Maclagan Manuscripts’, University of Edinburgh, (2021). Source: https://www.ed.ac.uk/information-services/library-museum-gallery/cultural-heritage-collections/school-scottish-studies-archives/manuscripts-collections/maclagan

Vintage Paper Company, ‘J. Whatman – The Master of Western Papermaking’, Vintage Paper Company, (2019) Source: https://vintagepaper.co/blogs/news/drying-paper-at-whatmans-springfield-mill

Be First to Comment