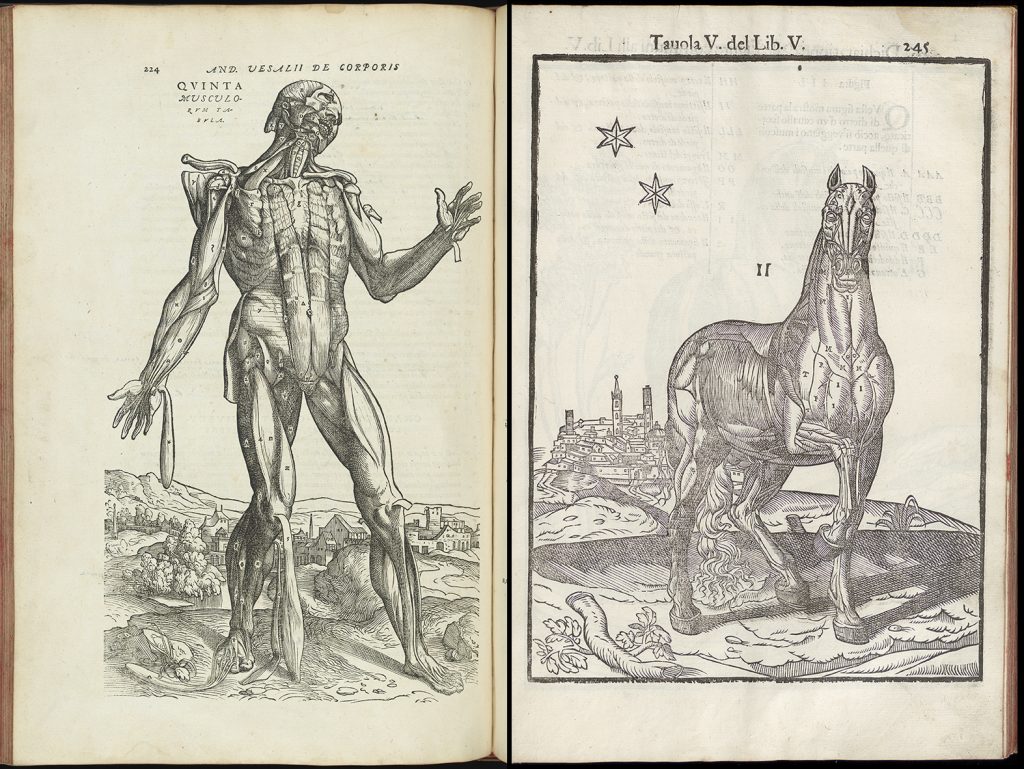

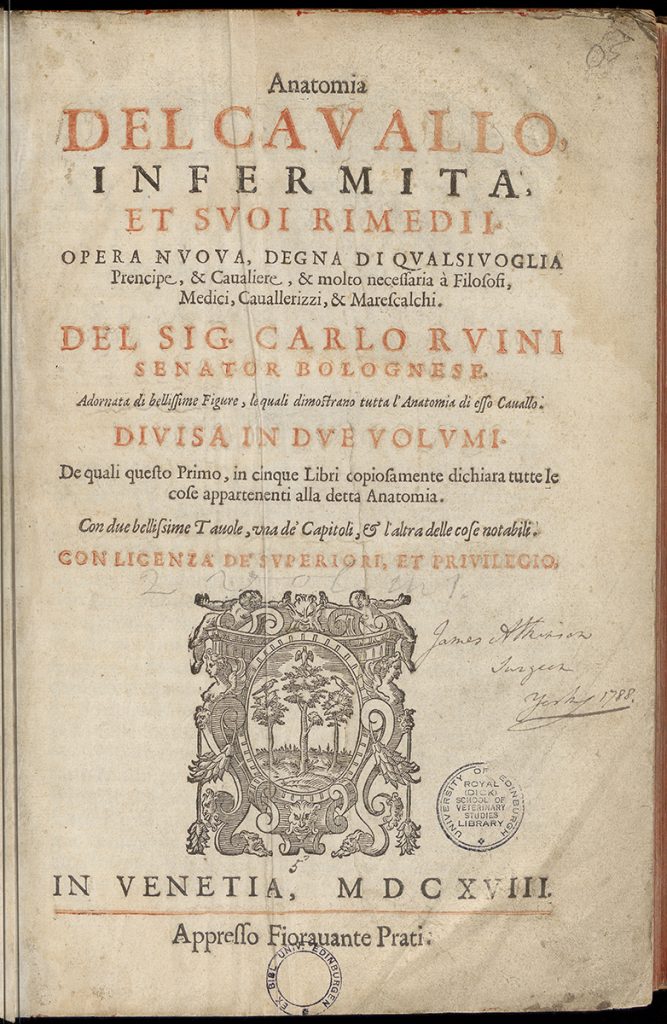

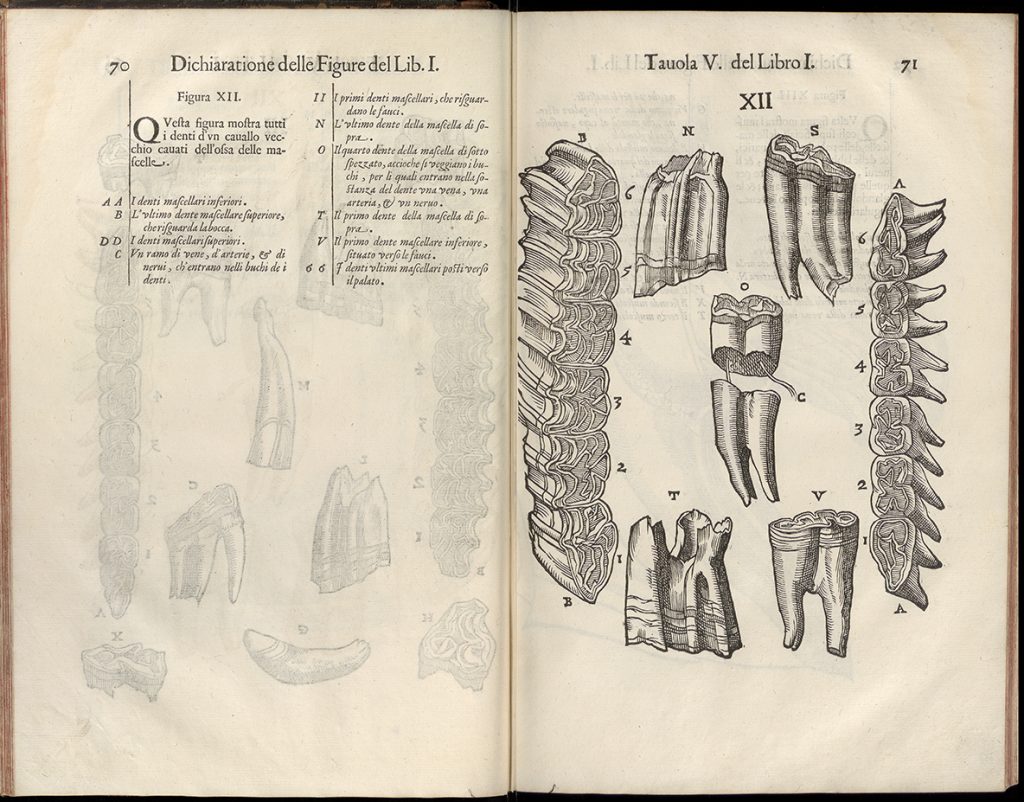

Recently I digitised Carlo Ruini’s ‘Anatomia Del Cavallo’ (The Anatomy of the Horse, Diseases and Treatments) as part of our Iconic’s collection on our i2S V-shape cradle scanner. It is a lavishly illustrated anatomic manual on the study of horses and was the first book to focus exclusively on the structure of a species other than man. In Ruini’s estimation, the horse combines ‘great love of man’ with natural docility and is celebrated for its many ways to bring pleasure and assistance to man that it is commemorated everywhere in monuments, tombs, poetry, and painting.

Our copy is a fifth edition and was printed in 1618, the original being published in 1598. This book was a milestone in equine veterinary publishing, and it was evident there were direct parallels in early human and horse medicine. Early veterinary science concentrated almost exclusively on the horse because Europe was largely dependent on horses for transport, draught, sport and warfare. The book in our collections was formerly in the Veterinary Library and contains both volumes. Historically, Edinburgh was a centre for veterinary studies from the early 19th century and this has resulted in the brilliant collections of books and manuscripts located here.

Anatomy books were highly prized by scholars and academics in the 1600’s, and these manuals were disseminated in limited print runs across Europe. Although Carlo Ruini was an aristocrat, senator and high-ranking lawyer, it was his pioneering horse anatomy manual that he is remembered for.

“It was at the hands of Ruini that the subject of equine anatomy jumped at a single bound from the blackest ignorance to relative perfection” (Smith, Frederick (1919) Early History of Veterinary Literature: and its British development. Vol 1 London: Bailliere, Tindall and Cox. p209)

Lacking in university membership, he was instead tutored by an expert in natural philosophy – Aristotelian philosopher Claudio Betti. The actual practice of anatomy and the dissection of humans was limited to those in professional training, something a gentleman like Ruini could not attempt. But the chance to contribute to the growing field of anatomical study was very tantalising to the wealthy, well-educated Ruini. His tutoring assisted his scientific learning, and with his large collection of horses, Ruini was able to conduct the studies reflected in his masterpiece.

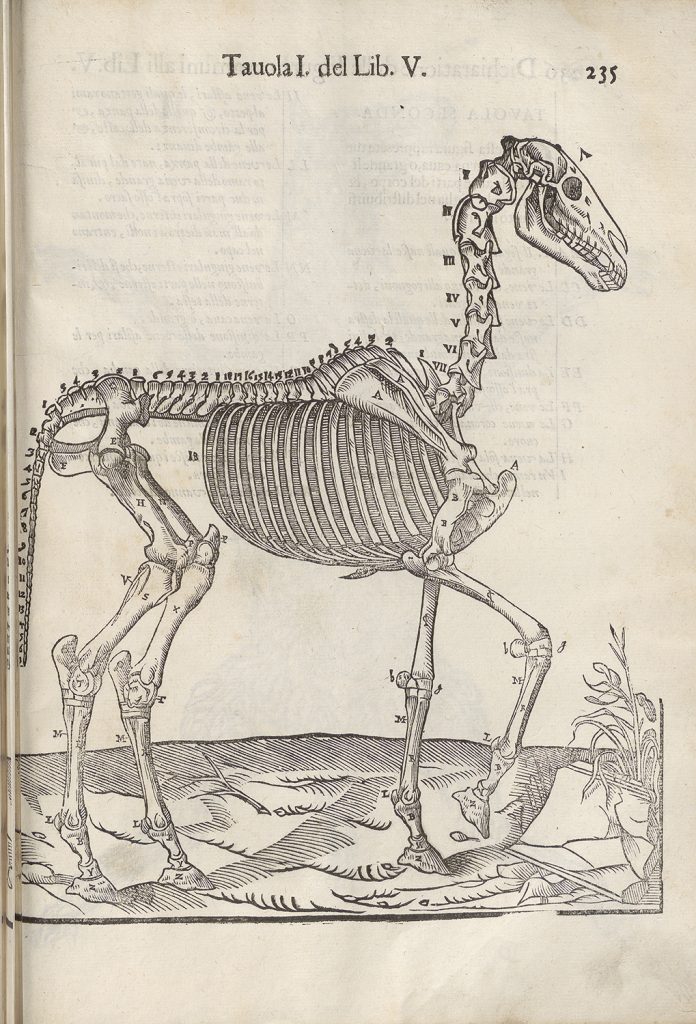

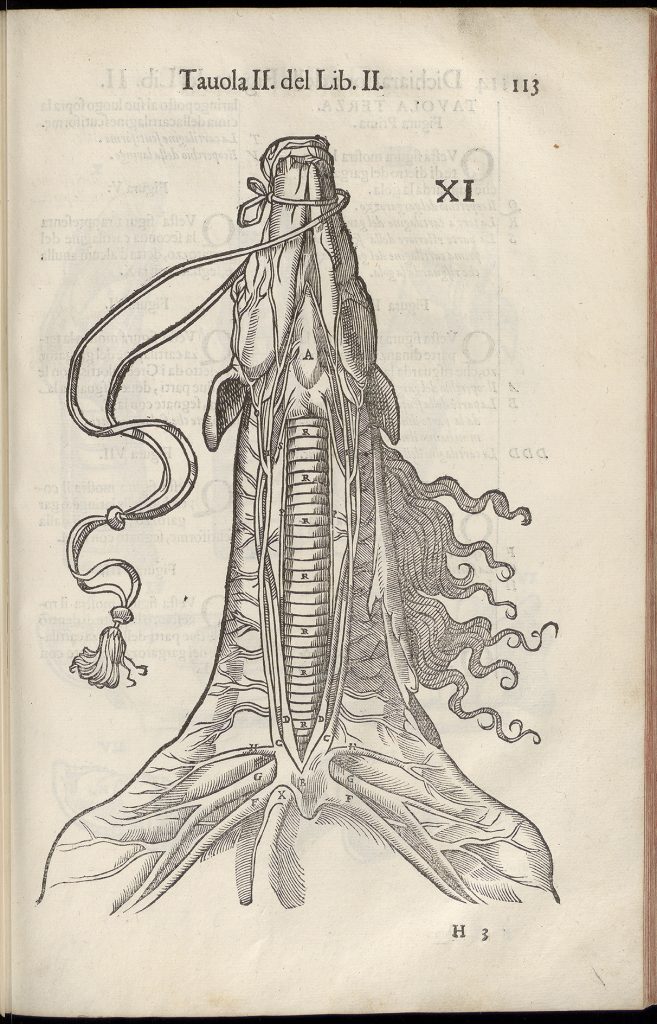

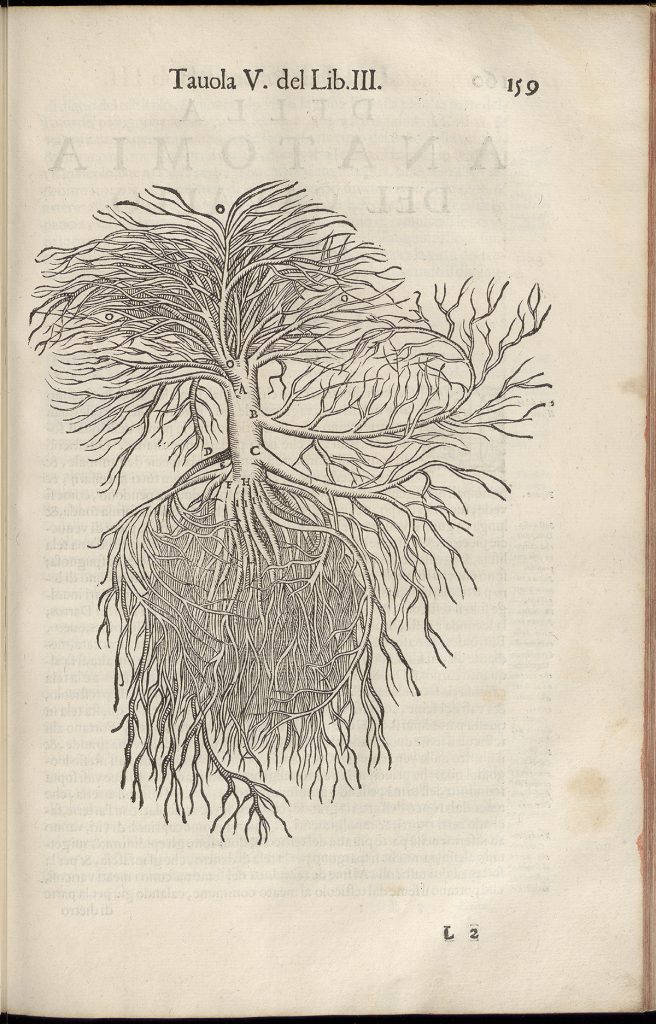

Volume I: Book I begins with an introduction where Ruini stresses the importance of “artful instruction” concerning the body of the horse, which leads to knowledge of its constitution and of the means of prolonging its life. After recounting the horse’s role in both work and recreation, Ruini concludes the introduction by explaining that his aims are to describe each part of the horse’s body, the nature of the ailments that afflict them, and the means of curing this worthy and noble animal. The first book deals mainly with anatomy, with the morphology of the head described in detail. The second book deals with the neck and its organs, the lungs, heart, thoracic muscles, blood vessels and nerves. The third book covers the liver, spleen, kidneys, stomach, intestines, peritoneum, and bladder. The structures of these organs and their positions are described, as are the lumbosacral region and its muscles, blood vessels and nerves. The fourth book describes the genital system and the fifth deals with the extremities.

Volume II deals specifically with equine diseases and their cures. Explaining that he has followed the methods used by Aristotle, Hippocrates and Galen to describe the human body, Ruini reflects on equine pathology, beginning with conditions of a general nature, such as fever, before progressing to descriptions of specific diseases. He considered it necessary to place pathology on a constitutional foundation because he believed that from knowledge of the horse’s physical disposition, one could more easily understand the nature of disease. Additionally, knowing the age of the horse, one could determine the appropriate treatment at any phase of an illness.

At the beginning of the first book, Ruini discusses at length the four Galenic humours (choleric, sanguine, phlegmatic and melancholic) and ways of telling a horse’s age. He then offers a detailed analysis of fever, distinguishing three types, giving general causes and a general cure, and discussing fevers of various origins. The second book considers various types of horse in regards to humoral pathology, using criteria based essentially on the concept of the four qualities (hot, cold, moist, dry). Ruini then examines a series of “affections” of the brain: frenzy, rage or fury, and insanity, leading to convulsions and paralysis. The book concludes with the diseases of the neck. In the third book Ruini describes the diseases of the heart and the lungs; in the fourth, the afflictions of the digestive tract, from diarrhoea to jaundice; and in the fifth, hernia, and problems of obstetrics. The sixth book deals with the diseases of the legs.

Some of the woodblock print illustrations have a very abstract quality about them, especially in the case of internal organs! There is an element of mystery shrouding these illustrations, perhaps because the artist is still unknown to us today. Rumours claim that the images were drafted by an artist from the workshop of Titian, the same workshop that Vesalius used. This perhaps is an indication of the work in the public’s eye, in terms of style, fluidity, artistry, detail, and importance. At the very least there is the same attention to detail, realism and dynamism, and many similarities, from the ribbons or ropes twisted or suspended around the horses (referencing Vesalius’ propped up skeletons), to the subjects in motion within a country landscape. Ruini’s diagrams of nerves and blood vessels hold a resemblance to the human anatomies, some in full abstraction from the body, and others in the context of the horse’s physical form.

On the whole, Ruini’s treatise was closely bound to the Scholastic tradition. It shows the effort made by its author (who certainly would have been familiar with Vesalius’ work), to produce a work that would manifest itself in the new direction being taken by sixteenth-century anatomy. It is with the utmost care and dedication that no detail is amiss, and considering the level of medical knowledge at the time, a great amount of research has gone into the compilation of this work, which would continue to be hugely influential for some 150 years after its first publication.

You can find the work in its entirety on our image repository:

https://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/view/search?search=SUBMIT&q=anatomia+del+cauallo&dateRangeStart=&dateRangeEnd=&QuickSearchA=QuickSearchA

Juliette Lichman

Project Digitisation Assistant

Thank you so much for this!