In this week’s blog post we take a closer look at the Dunfermline College of Physical Education Archives and attempt to join up the dots between the humble spider and the history of physical education in Scotland. Starting with the spider…

There are more than 45,000 species of spider found world-wide. An arachnid, they belong to a class of arthropods that include scorpions, mites and ticks. They can range in size from 0.11 inches (the tiny Samoan) to almost a foot (the Goliath birdeater tarantula). Metric, that’s around 2.5 mm up to 30.5 cm, or from a pin-head up to the length of your average class-room ruler. While a handful are dangerous to humans, the vast majority of spiders are harmless. They are critical to controlling insect populations.

The Jumping Spider – which can jump up to 50 times its own length

Take a closer look at the humble spider and you’ll discover some surprising athletic prowess. The jumping spider can jump up to an impressive 50 times their body length. That’s the equivalent of a human jumping higher than a 25 storey building. The male Peacock spider lifts its legs and shakes its body in synchronised movements in order to attract mates. And every spider produces silk, the strong, flexible protein fibre which they use to build webs, to travel, to anchor themselves for jumping, and to float serenely along in the wind. Allegedly, the silk is so strong that it can absorb three times as much energy as Kevlar, the material used to make bulletproof vests.

Since ancient times, throughout the world, the spider has featured in folklore and cultural tradition. This nifty creature has been assigned a variety of moral attributes and character traits. In some cultural traditions, the spider is seen as an evil arch-intriguer, weaving webs of duplicity, designed to entrap the innocent. In others, it is cast as a model of industry, wisdom and foresight. From Persia to Poland, spiders and caves have featured in the folklore of Kings and Prophets. A Jewish story tells of a spider protecting King David, who was hiding from King Saul, by weaving a protective web across the mouth of a cave. The Story of Hijrah from the Islamic faith tells the story of a spider spinning a web in a cave to protect the Prophet Muhammad.

Here in Scotland, many will be familiar with the fabled encounter of King Robert the Bruce (1274-1329) with a spider, first popularised by Sir Walter Scott in his series ‘Tales of a Grandfather’ (1828-1830). The story goes that after defeat by Edward I at the Battle of Methven (1306), a dispirited and demoralised Bruce fled into hiding. Holed up in a cave, Bruce observed a spider stoically attempt time and again to spin its web. Every time the spider fell, it began again, until at last, the web was spun. Inspired by the tenacious spider, Bruce is alleged to have told his troops, prior to defeating the English at the Battle of Bannockburn (1314), “if at first you don’t succeed, try, try and try again”. Bruce reigned King of Scots from 1306 until his death in 1329, and is somewhat revered as a national hero in Scotland.

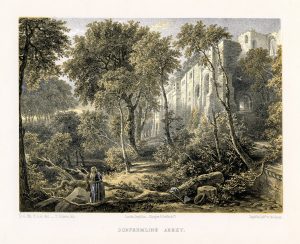

Lithograph of Dunfermline Abbey by T. Picken after D.O. Hill, 1847-1854 (Corson P.4114)

Dunfermline, the former capital of Scotland, has a long standing connection with Scottish kings. On his death in 1329, Robert the Bruce was the last of seven Scottish kings to be buried at Dunfermline Abbey. Sensationally, his remains were uncovered in 1818 and then re-interred at the Abbey in 1819. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, in 1891, the pulpit at Dunfermline Abbey was moved back and a monumental brass inserted to indicate the position of the royal vault.

Andrew Carnegie, the wealthy Scottish-born American industrialist and philanthropist, was born in Dunfermline in 1835. Carnegie was born just over fifteen years after the re-interment of Robert the Bruce at Dunfermline Abbey and only five years after Scott published his ‘Tales of a Grandfather’ featuring the legend of Robert the Bruce and the spider. The works of Scott were prominent in Carnegie’s education, enthusiastically relayed to him by his uncle, George Lauder, Snr. Carnegie’s ancestors had also been tenants on Broomhall Estate, the family home of Robert the Bruce’s descendants.

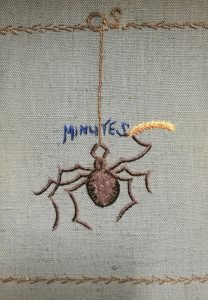

An embroidered spider motif on the front cover of the Dunfermline College of Physical Education Old Students’ Association Minute Book, 1912-1973 (Ref: EUA GD55/1/1/2)

Perhaps it is no surprise then, that the Carnegie funded Dunfermline College of Physical Education (DCPE), founded in 1905, should adopt the humble spider as its emblem. Its motto “Efforts are Successes” a distillation of Robert the Bruce’s alleged message to his troops. By 1905, Robert the Bruce and his spider were embedded in Scottish cultural tradition as a symbol of perseverance in the face of adversity. It is also fitting that this little creature assigned with traits of patience, dedication, resolve and resilience, and seemingly super-power athletic ability should become the lauded symbol of the college graduates.

The DCPE spider pops up in all manner of places throughout the the institution’s archives. The first minute book of the DCPE Old Students’ Association (OSA), which dates from 1912, features the spider motif intricately embroidered on its cloth cover. Open the cover and you will find revealed a controversy around the college brooch and its spider design. The minutes of 29 March 1929 read:

The Dunfermline College of Physical Education Brooch. Image courtesy of Lorna M. Campbell

The question of our badge having been raised. Mrs Manifold [the President of the Association] said it had been brought to her notice that our badge, not being registered, could be sold by Messrs R.W. Forsyth to any one who asked for it. She also said that she knew of a small shop-keeper who was making our pocket badge and had sold at least fifty, not necessarily to our members.

Inquiries were made to the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust (who owned the badge) to permit the spider design to be registered. Forsyth’s (a department store with premises in Edinburgh and Glasgow) offered to pay for the registration and were ‘prepared to protect their registration even to the point of a law-suit’ so strong were their feelings about the matter. Forsyth’s also committed to only sell badges to proven DCPE OSA members.

DCPE was founded as an instrument for improving the general health of the child but the story of the spider tells us it was about more than physical health. DCPE students and graduates were encouraged to align themselves to values of respectability, refinement, poise, deportment, and decorum. The moral standing and character of DCPE students was central to their teaching and their distinct identity in this area the source of some pride and cause for protection.

With growing secularisation, questions around how we shape the moral character and civic duty of society are as important now as ever before. Social and moral concepts such as loyalty, dedication, sacrifice, team-work, good citizenship, fairness, justice and responsibility are all tied up in the ethos of sports. But has the development of specialist sub-disciplines such as bio-mechanics, exercise physiology, sport psychology and motor learning led to a marginalisation of the social dimension of physical education? Has the renaming of physical education to ‘schools of exercise’ and ‘sports studies’ diluted its moral character? Does it matter? Asking these questions might lead us not just to a better understanding of the history of physical education, but of the human experience as a whole.

There are many ‘spider’ like stories to be found in the archives. This is one of thousands just waiting to be discovered. It is by uncovering and examining these stories that archives can help us to understand our past and our present, and subsequently, shape our future.

The records Dunfermline College of Physical Education and its’ Old Students Association are held at the University of Edinburgh Archives. You can search the catalogues of the Old Students’ Association online:

Dunfermline College of Physical Education Old Students’ Association

The catalogue of the college records will be made available online soon as part of our Wellcome Research Resource-funded ‘Body Language’ archive cataloguing project.

Sources and further reading:

- The National Geographic – Spiders

- On Walter Scott’s ‘Tales of a Grandfather’

- Isabella C. MacLean, The History of Dunfermline College of Physical Education, (1976).

- Phillips, M.G., Roper, A.P., History of Physical Education in ‘Handbook of Physical Education’ (2006).

- On Andrew Carnegie

With thanks to Clare Button for her background research of the minutes of the DCPE OSA (Ref: EUA GD55/1/1/2).

In 2018, a

In 2018, a  In 2020, we can now add the stresses and strains of coronavirus (COVID-19) into the mental health mix. There is little doubt that current measures around social distancing and restrictions on movement – in place to protect ourselves and others from coronavirus – are exacerbating the collective strain on mental and physical well-being. Mental health organisation websites (such as the

In 2020, we can now add the stresses and strains of coronavirus (COVID-19) into the mental health mix. There is little doubt that current measures around social distancing and restrictions on movement – in place to protect ourselves and others from coronavirus – are exacerbating the collective strain on mental and physical well-being. Mental health organisation websites (such as the