We continue our series on women in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland, with a particular focus on employment. The existence of women servants is not a surprise, but women miners may well be! We also look at some of the other jobs women undertook which have not already be mentioned.

Servants

In our previous post on women in Scotland, we mentioned the fact that it was hard to employ people as servants during the summer months because they earned more working on the land. However, there were still those who were not willing or able to work in agriculture. In Cross and Burness, County of Orkney, “women-servants receive from L. 2, 1Os. to L. 3 per annum ; but as they are much engaged at home in the plaiting of rye-straw for bonnets, they are unwilling to work in the field, and are generally employed, only in the care of cattle or as house-servants.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 100)

Conversely, farmers in Kinnell, County of Forfar, found it hard to employ women who were working in the weaving industry. “For the farmers, finding it difficult to induce women to leave the loom for the working of the green crop, have been constrained to bring workers from the northern counties. The engagement of these workers is generally for a certain period, at about 8d. or 9d. a day till harvest, when higher wages are necessarily given.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 404)

Many women had to move away from their parishes to work as servants, such as those in Kirkinner, County of Wigton. “Many of the young women go out as servants to Edinburgh, but particularly to Glasgow and Paisley.” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 17) In Walls and Sandness, County of Shetland, “many of the young women, in the character of servants, go to London, Edinburgh, Etc. in the Greenland ships.” (OSA, Vol. XX, 1798, p. 106)

As an aside, in Stornoway, County of Ross and Cromarty, there was a very interesting custom involving women servants! “The people of the town seldom have menservants engaged for the year; and it is a curious circumstance that, time out of remembrance, their maidservants were in the habit of drinking, every morning, a wine glass full of whisky, which their mistress gave them; this barbarous custom became so well established by length of time, that if the practice of it should happen to be neglected or forgotten in a family, even once, discontent and idleness throughout the day, on the part of the maid or maids, would be the sure consequence. However, since the stoppage of the distilleries took place, the people of the town found it necessary to unite in the resolution of abolishing the practice, by withholding the dear cordial from their female domestics, but not without the precaution of making a compensation to them in money for their grievous loss; and it is said, that even this is not satisfactory, and that, in some families, the dram is still given privately, to preserve peace and good order.” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 258)

Mining

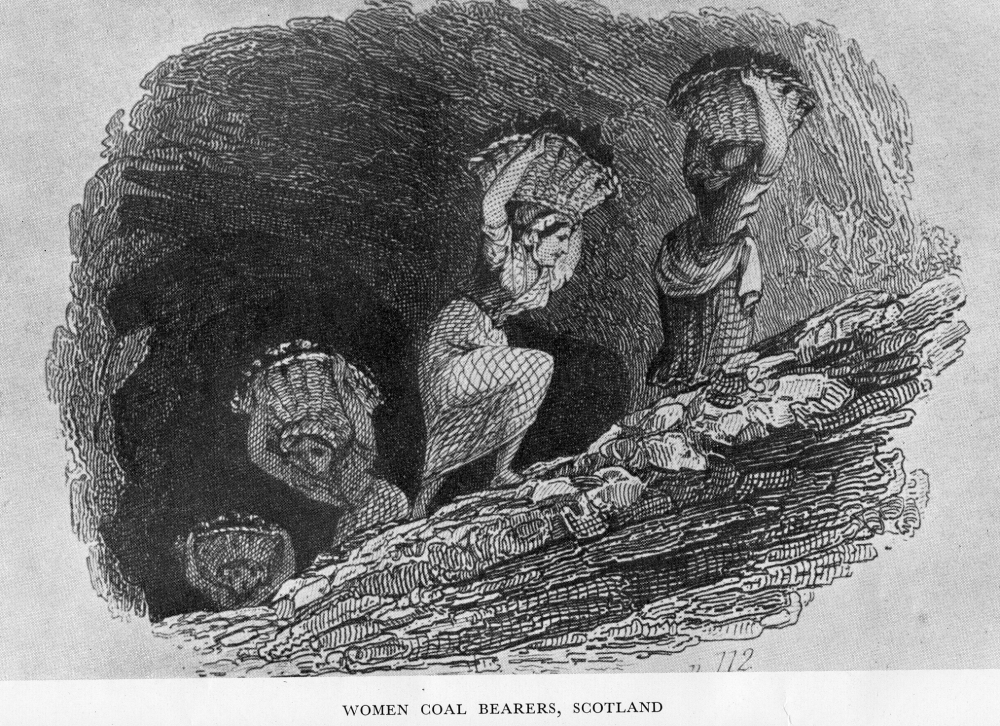

Women of all ages, even during the time of the Old Statistical Accounts of Scotland, worked in the mines, carrying the coal up to the surface on their backs! This was particularly prevalent in Alloa, County of Clackmannan and Tranent, County of Haddington. “The depth of a bearing pit cannot well exceed 18 fathom, or 108 feet. There are traps, or stairs, down to these pits, with a hand rail to assist the women and children, who carry up the coals on their backs.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 615) The women were called “bearers”, who carried about 1 1/2 cwt. on their backs, and ascended the pit by a bad wooden stair. In the deeper pits, the coals were carried to the bottom of the shaft by women, and then raised in wooden tubs by means of a “gin” moved by horses.” (NSA, Vol. II, 1845, p. 287) In Liberton, County of Edinburgh, “the stones from the mine or quarry were formerly carried to the bank-head by women with creels fastened on their backs, and when the works were in full operation, probably fifty women were thus employed.” (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 19) As reported in Hamilton, County of Lanark, “at Quarter, the first bed worth working is the 10 feet or woman’s coal, so called because it was once wrought by females. This is a soft coal, which burns rapidly; and although called the 10 feet coal, is in reality from 7 to 14 feet in thickness.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 258)

For the actual numbers who worked in the colliery of Alloa in 1780 you can take a look here: OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 619. There are also figures given for those working at the coal mines in the parish of Dunfermline, County of Fife. (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 476) In Lasswade, County of Edinburgh, “there are from 90 to 100 colliers, (pickmen). Women are still employed as bearers below ground; their number may be from 130 to 150.” (OSA, Vol. X, 1794, p. 281)

In the later Alloa parish report, found in the New Statistical Accounts of Scotland, mining was equated to slavery. It was reported that the condition of colliers had, in the last thirty years, improved “since the women were relieved from the most disgraceful slavery of bearing the coals, and the workman from all charge of the coals, the instant they are weighed at the pit. From, the circumstance of the wives remaining at home to attend to the domestic economy, the houses are much more comfortable and better furnished than they formerly were, and the whole style of living has been improved.” (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 33) It was felt that not having women working down the pits improved both the character and habits of the people. In the parish report of Tranent, County of Haddington, it was noted that “among a population of colliers, it cannot be expected that the habits of the people should be cleanly; and the injurious practice of women working in the pits as bearers, (now happily on the decline with the married females,) tends to render the houses of colliers most uncomfortable on their return from their labours, and to foster many evils which a neat cleanly home would go far to lessen.” (NSA, Vol. II, 1845, p. 295)

Other jobs!

Here are some other jobs undertaken by women found in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland.

- Boot-binding

Linlithgow, County of Linlithgow – “Thirty women are also employed as women’s boot-binders, whose weekly wages average 4s. 6d.” (NSA, Vol. II, 1845, p. 180)

- Fuel manufacture

Rathven, County of Banff – “It is the province of the women to bait the lines; collect furze, heath, or the gleanings of the mosses, which, in surprising quantity, they carry home in their creels for fuel, to make the scanty stock of peats and turfs prepared in summer, last till the returning season.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 424)

Kirkinner, County of Wigton – “The day-light, during the winter, is spent by many of the women and children in gathering elding, as they call it, that is, sticks, furze, or broom, for fuel, and the evening in warming their shivering limbs before the scanty fire which this produces.” (OSA, Vol. IV, 1792, p. 147)

Appendix for Kincardine, County of Perth – “The women declare they can make more by working at the moss than at their wheel and such is their general attachment to that employment, that they have frequently been discovered working by moon-light.” (OSA, Vol. XXI, 1799, p. 175)

Snizort, County of Inverness – “The fuel is peats, which the women carry home in creels on their backs, from a very great distance.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 295)

Lismore and Appin, County of Argyle – “Peats are the only fuel in both parishes. The process of making them in Lismore is difficult beyond conception, as they are first tramped and wrought with men’s feet, and then formed by the women’s hands. There is a necessity for this; because the substance of which they are made contains no fibres to enable them to cohere or stick together. This tedious operation consumes much of the farmer’s time, which, in a grain country, might be employed to much better advantage; and affords serious cause of regret that the coal-duty is not taken off, or lessened, which would remove the everlasting bar to the success of the fishing villages, and to improvements in general over all the coasts of Scotland.” (OSA, Vol. I, 1791, p. 490)

- Varnishing wooden boxes

Old Cumnock, County of Ayrshire – “One set of artists make the boxes, another paint those beautiful designs that embellish the lids, while women and children are employed in varnishing and polishing them. The process of varnishing a single box takes from three to six weeks. Spirit varnish takes three weeks, and requires about thirty coats; while copal varnish, which is now mostly used, takes six weeks, and requires about fifteen coats to complete the process. When the process of varnishing is finished, the surface is polished with ground flint; and then the box is ready for the market.” (NSA, Vol. V, 1845, p. 486)

- Plaiting straw

Orphir, County of Orkney – “Almost all the young women have, for many years, been employed in winter in plaiting straw for bonnets.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 20)

Stromness, County of Orkney – “There are a few straw plait manufacturers, who employ a number of women in the town as well as in the country. This manufacture has been, for some time past, upon the decline; and, being at all times dependent upon the caprice of fashion, has lately afforded a scanty subsistence to the many young females who totally depend on it for their support. They are now allowed to plait in their own homes, which has been found more conducive to their health and morals, than doing so collectively, in the houses of the, manufacturers, which was the original custom. -There is a small rope manufactory, where ropes of various kinds are made, both for the shipping and for country, use. From the former Account, it appears there was a considerable quantity of linen and woolen cloth manufactured. This business has now wholly ceased here, being superseded by the perfect machinery now in use.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 32)

- Salt sellers

Duddingston, County of Edinburgh – “Their labours afforded employment to above 40 carriers, all women, who retailed the salt in Edinburgh, and through the neighbouring districts.” (OSA, Vol. XVIII, 1796, p. 368)

- Lace makers

Hamilton, County of Lanark – “The lace trade, established here about eight years ago by a house at Nottingham, which sent down a number of English women, who took up schools and taught the tambourers here the art, is now in a thriving state, and is contributing greatly to the happiness and comfort of the community.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 294) “From a census taken some months ago, and which seems to be accurate, there has been an increase [in population] of 309, which may be attributed to the introduction and flourishing condition of a lace-manufactory, which now employs a great many females.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 276)

- Potato-starch makers

Spott, County of Haddington – “The only thing of this sort [manufactures] carried on in the parish, is a manufactory of potato-starch, or flour, on the farm of Easter Broomhouse. It employs six women for six months in the year. The flour is principally used by manufacturers of cloth; and sometimes by bakers and confections in large towns.” (NSA, Vol. II, 1845, p. 230)

For a fascinating insight into the industries found in Scotland in the nineteenth century take a look at the book ‘The industries of Scotland; their rise, progress, and present condition‘ by David Bremner, published in 1869.

Conclusion

The last three blog posts illustrates just how important the role was for women in society. They worked in all sorts of sectors, including manufacturing, agriculture, fishing, and even mining at one point. They supported themselves and helped support their families, showing resourcefulness, adaptability, and willingness to work hard.

We will continue this series on women in Scotland by looking more generally at the impact women’s work had on society, as well as the impact society had on women.