This is the last post in our series on crime and punishment in late 18th-early 19th century Scotland, this time focusing on prisons. In the Statistical Accounts there is a lot of fascinating, detailed information on prisons and bridewells (prisons for petty offenders). In some cases, there was simply a lock-up in a town-house, rather than a purpose-built building. Below, we will look at some specific prisons found throughout Scotland, first looking at the cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh and then towns. It is particularly interesting when we compare between the Old and New Statistical Accounts and see what changes there have been.

Prisons in Cities

Glasgow

By the 1780s, the population of Glasgow had greatly increased due to the expansion of manufacturing. It became clear that there was a “necessity of a bridewell, or workhouse, for the punishment and correction of lesser offences.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 513) So, in 1789, existing buildings were converted from granaries into a bridewell. “These have been gradually increased to the number of 64, where the prisoners are kept separate from one another, and employed in such labour as they can perform, under the management of a keeper, and under the inspection of a committee of council, who enquire into the keeper’s management, etc.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 514)

Even at this time it was felt very important that the prison was of an adequate standard. Town Councillors inspected the prison and reported their findings, including anything to be rectified or altered. The keeper also kept records of each prisoner, noting down the details of their sentence, the wages they received for their labour, and after expenses were subtracted, the surplus paid to the prisoner when they left the prison. For some, this amounted to L. 5 to L. 7. (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 514)

However, by the time of this parish report written in 1793, it was noted that “the growing manufactures and population of the city requiring more extensive accommodations, than the present bridewell can afford, the Magistrates and Council propose to erect a new one, more properly calculated for the ends proposed, and on such a plan, that additions can be made to 1, from time to time, as the circumstances of the city may require.”(OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 514) Yet again, by the time of the New Statistical Accounts of Scotland, “the gaol at the cross had become deficient in almost every requisite.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 214) At that point, it was serving not just the city, but also occasionally the counties of Lanark, Renfrew, and Dumbarton. On the 13th February 1807, “the magistrates and council resolved to erect a new gaol and public offices in a healthy situation adjoining the river, at the bottom of the public green. This building, which cost L. 34,800, contains, exclusively of the public offices, 122 apartments for prisoners.” To discover more about the prison’s facilities (which may surprise you!) take a look at the parish report for Glasgow. (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 214)

On the 8th May 1798, a new bridewell was opened in Duke Street, Glasgow, which again quickly became ill-equipped for such a fast-expanding city. (Can you see a pattern emerging?!) It was, therefore, extended further and was opened on Christmas Day 1824. “It combines all the advantages of modern improvement, security. seclusion, complete classification, and healthful accommodation.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 215)

In the Statistical Accounts, there are several examples of tables giving the number of prisoners and associated costs. Below is an example for the Glasgow bridewell, covering the commitments in 1834.

| Males above 17 years of age, | 313 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Males below 17 years of age, | 222 | ||||||||||||||||||

| =1035 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Females above 17 years of age, | 864 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Females below 17 years of age, | 68 | ||||||||||||||||||

| = 932 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Total commitments, | 1967 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Remained on 2d of August 1833, | 356 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Prisoners in all, | 2323 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Liberated during the year, | 2030 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Remaining on 2d of August 1834, | 293 | ||||||||||||||||||

| The average number daily in the prison was 320; viz. males, 162; females, 158. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Abstract accounts for the year ended 2d of August 1834. | |||||||||||||||||||

|

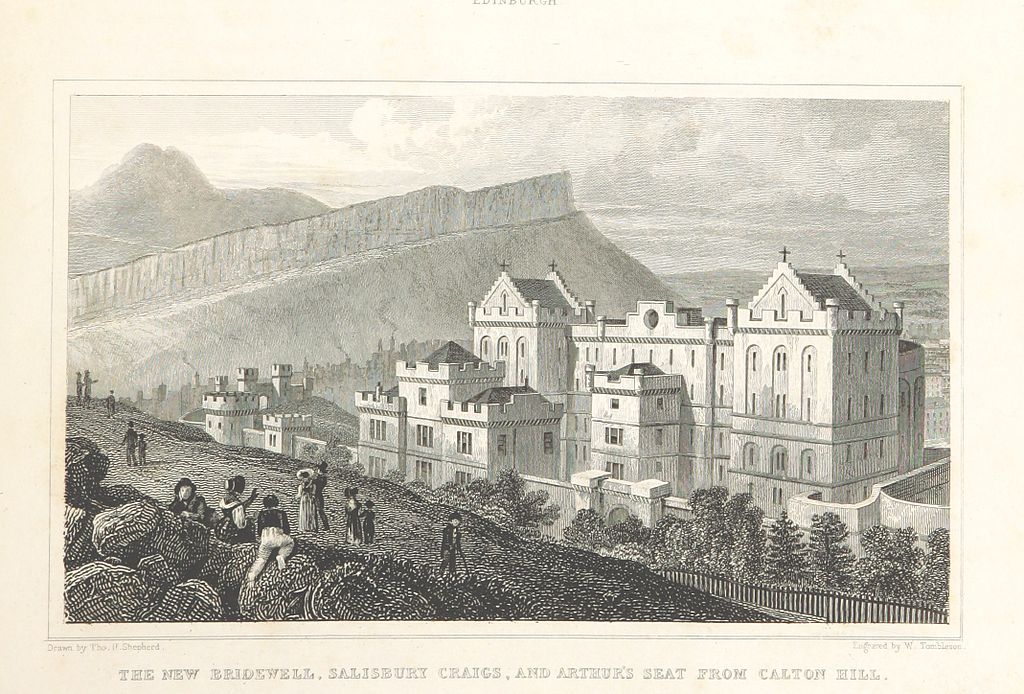

Edinburgh

All the way back in 1560 the old prison or Tolbooth was founded and stood immediately west of St Giles’ church. However, this was pulled down in 1817, the same year a new prison was opened on Calton Hill. There is a very detailed description of the Calton Hill prison in the parish report of Edinburgh, written in 1842:

“It is a very ornamental castellated structure in the Saxon style; and is 194 feet long by 40 feet in width. The interior is divided into six classes of cells; four for males, and two for females; with an airing ground attached to each. There are two stories of cells, one above the other. To each of these divisions of cells on the ground floor there is a day room with a fire-place; and an airing ground common to fill the cells of the division. Each cell is for the reception of one prisoner; and is 8 feet by 6. A wooden bed is fixed into the wall, and there is a grated window and air holes in the wall for full and free ventilation. There are in all fifty-eight cells.” (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 719)

The new Bridewell, Salisbury Crags, and Arthur’s Seat from Calton Hill, Edinburgh, 1829. Thomas H. Shepherd [Public domain].

In the Appendix for Edinburgh, County of Edinburgh, a few key dates have been given. “In 1748-The first correction house for disorderly FEMALES was built, and it cost L. 198: 0: 4 1/2. N. B. This is the only one Edinburgh yet has. In 1791-Manners had been for some years so loose, and crimes so frequent, that the foundation of a large new house of Correction, or Bridewell, was laid on the 30th of November, which, on the lowest calculation, will cost L. 12,000; and this plan is on a reduced scale of what was at first thought absolutely necessary. In 1763-That is from June 1763 to June 1764, the expence of the Correction house amounted to L. 27: 16: 1 1/2. In 1791, and some years previous to it. The expence of the Correction house had risen to near L. 300,-ten times what it had been in the former period; and there is not room for containing the half of those that ought to be confined to hard labour.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 612)

Prisons in Towns

We have looked at the prison situation in the large cities. But, how about the situation in smaller towns? Below, we look at some examples throughout Scotland.

Kirkcaldy

As claimed in the parish report for Kirkcaldy, its jail is the best in Fife! “Under the New Prison Act, its management has been much improved. The prisoners are constantly employed, and great care is taken that proper attention be paid to their health, their diet, their education, and religious instruction. It is now a place more for the reformation than the punishment of prisoners.” (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 770)

Hawick

“The Jail, which forms a part of the town-house, and consists of a very small apartment, is neither properly secured, nor capable of being used without endangering the health of its inmates. For these reasons criminals are generally conveyed to the county town, a mode of procedure which is not only attended with considerable expense, but which, when taken in connection with a glaring deficiency of police, presents serious obstacles to the authorities in arresting the progress of crime and enforcing the authority of the laws. The number of convictions, inclusive of cases, brought not only before the magistrates and justices of peace, but before the Sheriff, and the circuit court at Jedburgh, amounted in 1838 to 58.” (NSA, Vol. III, 1845, p. 417)

Dumfries

“The Court-house is an elegant and commodious structure, wherein the circuit and sheriff-courts, the quarter session and the county meetings are held. Opposite to this stands a heavy-looking building, which was at first intended for a court-house, but is now converted into a Bridewell, the interior of which is arranged on the same plan with that of Edinburgh, but on so small a scale, that it is thought, from the facility with which the prisoners can hold intercourse with one another, to be very ill adapted for a place of confinement. Behind this, in a low damp yard, and surrounded by a high wall, is situated the county Jail, which, along with the Bridewell, was built in 1807. Previously to that period, the jail was in the centre of the town. A vaulted passage under the street, forms a communication between the prison-yard and the court-house. The debtors have the liberty of exercising themselves within the enclosed yard.” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 14)

Inverness Steeple and Tolbooth, 2008. [Photo credit: Dave Conner from Inverness, Scotland [CC BY 2.0]].

As noted in the parish report for Aberdeen written in 1835, “the ancient jail of Inverness consisted only of a single damp dingy vault, in one of the arches of the stone bridge, and which (subsequently used as a mad-house) was only closed up about fifteen years ago. It was succeeded by another prison in Bridge Street, which, from the notices of it in the burgh’s records, must also have been a most unhealthy and disagreeable place of confinement. The present jail was erected in 1791, and cost L. 1800, the spire having cost about L.1600 more. ” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 34) (In fact, the spire is the only part of the building left standing, as can be seen in the picture on the right.)

“Besides prisoners for debt, all those charged with crimes from the northern counties are sent here previous to their trial before the circuit.courts of Jisticiary, which sit at Inverness twice a-year. Although a great improvement at the time of its erection, this prison is now found to be too small and very inconvenient, there being no proper classification of delinquents, while there is no open court or yard for them to walk in, nor can any manual employment be required of them at present.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 34)

Porttree

In the parish of Porttree, County of Inverness, there was only one prison, where, in 1840, 16 offenders resided – “eleven for riotous conduct, four for housebreaking and theft, and one for forgery.” For some time in the past this prison was insecure, with instances of prisoners actually managing to escape! The bad conditions did not help matters. “Into the jail they are thrown without bed, without bedding, without fire, and with but a small allowance for their subsistence. “By the humanity, however, and charity of some benevolent persons in the neighbourhood, these privations have been partly alleviated, if not removed.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 234)

Cupar

In the parish report of Cupar, County of Fife, in 1796, the Reverend George Campbell wrote that “the prison of Cupar, which is the public jail, for the very populous and wealthy county of Fife, yields perhaps to none, in point of the meanness, the filth, and wretchedness of its accommodations… Apartments in one end of a town-house acted as a place to secure and punish those who have fallen foul of the law. “The apartment destined for debtors is tolerably decent, and well lighted. Very different is the state of the prison under it, known by the name of “the Iron-house,” in which persons suspected of theft, etc. are confined. This is a dark, damp, vaulted dungeon, composed entirely of stone, without a fire-place, or any the most wretched accommodation. It is impossible, indeed, by language, to exaggerate the horrors which here present themselves” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 142)

In many parishes there was a concern that when a prison was built in a neighbouring or nearby county that it would cause the displacement of criminals into their area. This was certainly the case in Cupar, with the parish report stating that in such a wealthy county as Fife, there should be better prisons. “It is to be hoped, however, that the period is now happily arrived, when the landholders of Scotland, having more humane sentiments and enlarged views, than those who went before them, will attend to the wretched state of the different county jails” and would contribute to the building of more modern prisons. (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 143) “A measure of this kind will appear every day of more pressing necessity, when the Bridewell now building at Edinburgh shall be finished. If Fife takes no step to defend itself against the influx of pickpockets, swindlers, etc. which may naturally be expected, it will become the general receptacle of sturdy beggars and vagrants; and the rising industry of the county must be exposed to the depredations of the desperate and the profligate, from every quarter*.” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 144)

In 1844, the number of prisoners committed to Cupar Prison was 37. “Of these, 15 were for debt, and 22 for stealing, assault, and such crimes as commonly occur in a populous country.” However, according to the parish report, the prison needed improvements. “The accommodation that it affords is uniformly condemned as most unworthy of the town and county. The lodging is bad, and reckoned unhealthy,-there is no room for the classification of criminals,-there is no chapel or place of worship attached; and consequently, any attempt to reclaim or improve those that are once committed to it, becomes absolutely hopeless.” (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 18)

Dundee

Dundee was another parish which felt the effects of prisons being built elsewhere. “Since Bridewells, or penitentiary houses, have been established in Edinburgh and Glasgow, Dundee has been much more pestered than formerly, with vagrants and persons of doubtful character, and swindling and petty thefts are more frequent. This will probably produce a Bridewell in Dundee. An establishment of this kind is certainly necessary, and the common prisons, and present inflictions of justice, are by no means sufficient to supply its place. With respect to our prisons, though among the best in Scotland, they are destitute of any court or area where the prisoners may enjoy the open air. This, however, is at present, the less necessary, as the laws of the country are supposed inhumanely, to exclude debtors from the privilege of breathing the same air with others; and, it is but very seldom, that felons suffer long confinement, in the prisons of places not visited by the Circuit Courts of Justiciary.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 248)

Other Prisons

Here are some of the other prisons you can read about in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland: Linlithgow, County of Linlithgow; Montrose, County of Forfar; Falkirk, County of Stirling; Perth, County of Perth; Dingwall, County of Ross and Cromarty; Irvine, County of Ayrshire; Blairgowrie, County of Perth; Ayr, County of Ayrshire; Inverary, County of Argyle; Wick, County of Caithness; and Aberdeen, County of Aberdeen. This is by no means a definitive list!

Conclusion

The Statistical Accounts of Scotland provides a wealth of knowledge about prisons throughout Scotland, some very detailed and giving actual figures, for example Aberdeen, County of Aberdeen (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 83), Peebles (NSA, Vol. III, 1845, p. 182), Inverary, County of Argyle (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 42) and Wick, County of Caithness (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 175). You can discover when and where prisons and bridewells were built, descriptions of the buildings, living conditions, numbers of prisoners and crimes committed, work carried out by the prisoners and, for some of the larger prisons, even the costs of running them. Many parish ministers also wrote about the issues faced by the parishes and their prisons, especially the poor prison conditions and lack of cells. It may be a surprise to learn that many parish reports state how abominable prison conditions were, calling for more modern, larger prisons to be built to deal with the increased number of offenders.

Although this is the last post in our crime and punishment series, there are many other areas you could research, including crime statistics, policing, law courts and acts of law. This goes to show how comprehensive and enthralling a resource both the Old and New Statistical Accounts of Scotland are!