In our last post we looked at women working in manufacturing. In fact, in many parishes it was the women who predominantly worked in this sector, spinning. However, there were also women still working on the land. In Morebattle and Mow, County of Roxburgh, “little more yarn is spun than what is necessary for private use. The women in this part of the country being accustomed to work much in the agricultural operations of the field, are little disposed for sedentary employments, and therefore, in general, sit down to the spinning wheel with great reluctance. From the present disposition and habits, both of males and females in this place, the introduction of manufactures among them would not, it is probable, meet with great success.” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 510)

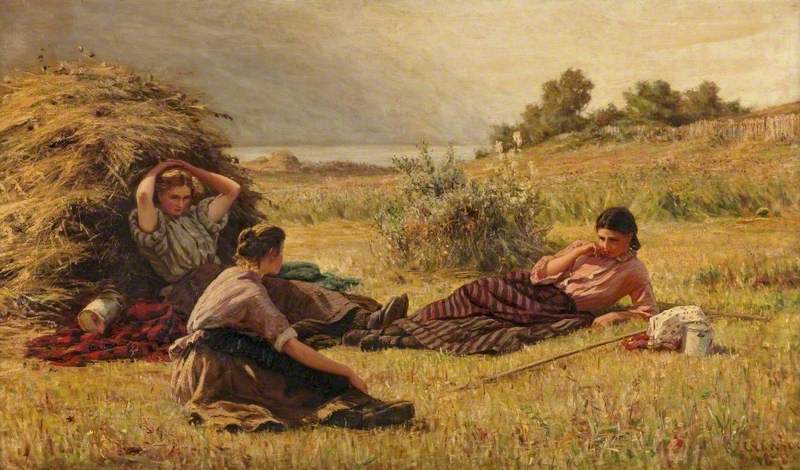

Working in the fields

As reported in the parish of Watten, County of Caithness, “our women, perhaps, are more employed in the field, for at least 8 months in the year, than in most other places of the kingdom.” (OSA, Vol. XI, 1794, p. 271) The simple reason for this was that women earned more working in the fields. This actually lead to a lack of servant posts being filled, especially during the summer months, such as was the case in Torphichen, County of Linlithgow. “Servant women are difficult to be had too in summer, as they make nearly as much in harvest as their half year’s wages would be, and can do very well the rest of the time by spinning flax; indeed there are many women who do very well the year round, by spinning flax, with their harvest wages.” (OSA, Vol. IV, 1792, p. 471) This was also reported by the parish of Alford, County of Aberdeen, where “work is never done by the piece or day, but an agreed-upon-sum, together with the reapers victuals, (frequently accompanied by very ridiculous stipulations)… These harvest fees have been rising for some years, and are now 1 L. 15 s. or 2 L. for a man, and 1 L. for a woman, besides victuals”. (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 469) We will look a little more closely at servants in our next post.

Agricultural work was very hard and labourious, just as it was for men, and this was duly noted in the parish reports. It included clearing weeds, hoeing, carrying creels of manure or produce, sowing, reaping, dressing corn. Here are some examples of the work women actually undertook on the land:

Stornoway, County of Ross and Cromarty – “The ground being prepared, as soon as the season permits, the seed is sprinkled from the hand in small quantities; the plots of ground being so small, narrow, and crooked, should the seed be cast as in large long fields, much of it would be lost. After sowing the seed, a harrow with a heather brush at the tail of it is used, which men and women drag after them, by means of a rope across their breast and shoulders. The women are miserable slaves; they do the work of brutes, carry the manure in creels on their backs from the byre to the field, and use their fingers as a five-pronged grape to fill them.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 131)

Prestonpans, County of Haddington – “The land is cleared of weeds, by sowing in drills, and horse-hoeing the interstices; and women are often employed to pick them out with the hand. The land designed for wheat is ploughed as soon as it is cleared of the preceding crop.” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 62)

Kingsbarns, County of Fife – “Much of the wheat and beans on the low lands are sown in drills, which, along with the potato and turnip, give a vast deal of employment to young women in hoeing. About 113 are so occupied. In fact, from the time of planting potatoes, which usually begins at the end of April, until harvest be completed, they are seldom off the fields. Their payment when so employed is 8d. per day, without meat; and when lifting potatoes, 1s. with their dinner. A good labourer with the spade obtains from 1s. 4d. to 1s. 6d. per day in summer, and from 1s. to 1s. 2d. in winter. The harvest wages are, for men, L. 2, with some potato and lint ground, and supper meal, and for women, L. 1, 13s. with the above bounties.” (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 97)

Stornoway, County of Ross and Cromarty – “In this, and all the other parishes of the island, the women carry on as much at least of the labours of agriculture as the men; they carry the manure in baskets on their backs; they pulverize the ground after it is sown, with heavy hand-rakes, (harrows being seldom used), and labour hard at digging the ground, both with crooked and straight spades.” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 258)

Snizort, County of Inverness – “The soil is broken up by the caschrom, and when sown is harrowed by women, who are also employed in carrying out the manure in creels to the field, and other drudgeries of the same nature. It cannot but give pain to every benevolent mind to see not only young women whose delicate frame should exempt them from such hard labours, but even mothers employed as beasts of burden.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 293)

Kilmuir, County of Inverness – “When the ground is thus turned over and sown, the harrowing department generally falls to the lot of the women. Owing to the lightness of the narrow, which they are able to drag after them, the ground cannot be made, sufficiently smooth, and to remedy this they commence anew with the “racan,” which is a block of wood having a few teeth in it, with a handle about three feet in length. As they have few or no carts, they are under the necessity of carrying manure, peats, potatoes, and all such commodities in creels upon their backs. So little do the women care for the weight of the creel, though full of peat or potatoes on their backs, that, while walking with it, they are engaged either at spinning on the distaff, or knitting stockings. Sacks, or canvas bags, are seldom used; instead of which they have bags which they call “plats,” made of beautifully plaited bulrushes. Of the same useful material they likewise make their ropes, and sometimes cables for their boats. Although the agricultural processes of the small tenants are in this manner conducted, the tacksmen are possessed of ploughs and carts, and other implements of husbandry, of the best and most approved modern construction.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 279)

Kilmuir, County of Inverness – “The women, for the most part, thrash the corn by a light flail of peculiar but simple construction. The quantity of barley raised is but very small, which the natives seldom reap with a sickle, but when ripe they pull it from the roots, then equalize it, and tie it up in small bunches. When it becomes seasoned, they cut off the ears with a knife, and preserve the straw for thatching their dwellings.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 285)

Bedrule, County of Roxburgh – A number of women were “chiefly employed in what is called out-work, as hoeing the turnip, making the hay, reaping the harvest, removing the corn from the stack to the barns etc.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 558)

Strath, County of Inverness – “The mode of dressing the corn to be ground by what is called gradan, is here still in use. By this operation they save the trouble of threshing and kiln-drying the grain. Fire is set to the straw, and the flame and heat parches the grain; it is then made into meal on the quern. This meal looks very black, but tastes well enough, and is esteemed very wholesome. The whole of the work is performed by the women. The only apology given by themselves, for this mode of preparing the grain, is, that the quantity of grain which the generality have is very small, and many of them are at a great distance from a mill.” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 228)

Transportation of goods

As well as working on the land, women transported produce to the markets to be sold. In Inveresk, County of Edinburgh, “the whole produce of the gardens, together with salt, and sand for washing floors, and other articles, till of late that carts have been introduced, were carried in baskets or creels on the backs of women, to be sold in Edinburgh, where, after they had made their market, it was usual for them to return loaded with goods, or parcels of various sorts, for the inhabitants here, or with dirty linens to be washed in the pure water of the Esk.”(OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 15) Yes, women even carried sand to Edinburgh, which was the hardest labour of all and least paid! “For they carry their burden, which is not less than 200 lb. weight, every morning to Edinburgh, return at noon, and pass the afternoon and evening in the quarry, digging the stones, and beating them into sand. By this labour, which is incessant for six days in the week, they gain only about 5 d. a day.” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 17)

The fishing industry

Women also worked in the fishing industry, undertaking a variety of tasks, including making the fishing nets, gathering bait, baiting hooks, gutting the fish and taking the fish to market (often involving heavy loads and miles of trekking). In the parish of Avoch, County of Ross and Cromarty, women even carried the men to the boats on their backs! While in Burntisland, County of Fife, women drunk undiluted spirits to help them get through the disagreeable work of curing herrings.

Fisher Jessie Statue, Peterhead. Iain Macaulay available through license CC BY-SA 2.0. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/) via Wikimedia Commons.

In Dundee, County of Forfar, “women from Achmithie carry crabs, lobsters, and dried fish to Dundee, a distance of twenty-four miles, and return with the price in the evening. These women are

particularly strong and active.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 40)

In Rathven, County of Banff, men “marry at an early age, and the object of their choice is always a fisherman’s daughter, who is generally from eighteen to twenty-two years of age. These women lead a most laborious life, and frequently go from ten to twenty-five miles into the country, with a heavy load of fish. They seldom receive money for this fish, but take in exchange meal, barley, butter, and cheese. They assist in all the labour connected with the boats on shore, and show great dexterity in baiting the hooks and arranging the lines.” (NSA, Vol. XIII, 1845, p. 257)

Slains, County of Aberdeen – “The women are generally employed to gather the bait. About the one half of the fish caught here is carried in boats to Leith, Dundee, or Perth; the other half is carried by the women to Aberdeen…” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 277)

Uig, County of Ross and Cromarty – “All the people dwell in little farm-villages, and they fish in the summer-season. The women do not fish; but almost at all times, when there is occasion to go to sea, they never decline that service, and row powerfully.” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 284)

Avoch, County of Ross and Cromarty – “No less remarkable are the inhabitants of this thriving village in general, for their industry and diligence. They manufacture, of the best materials they can procure, not only all their own fishing apparatus, but also a great quantity of herring and salmon nets yearly, for the use of other stations in the North and West Highlands. From Monday morning to Saturday afternoon, the men seldom loiter at home 24 hours at a time, when the weather is at all favourable for going to sea. And the women and children, besides the care of their houses, and the common operations of gathering and affixing bait, and of vending the fish over all the neighbouring country, do a great deal of those manufactures.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 630) “Their women are, in general, hardy and robust, and can bear immense burdens. Some of them will carry a hundred weight of wet fish a good many miles up the country. As the bay is flat, and no pier has yet been build, so that the boats must often take ground a good way off from the shore, these poissardes [fish wives] have a peculiar custom of carrying out and in their husbands on their backs, “to keep their men’s feet dry,” as they say. They bring out, in like manner, all the fish and fishing tackles, and at these operations, they never repine to wade, in all weathers, a considerable distance into the water. Hard as this usage must appear, yet there are few other women so cleanly, healthy, or so long livers in the country.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 637)

Boindie, County of Banff – “One cooper and three women wait on shore for each herring-boat. Coopers’ wages are 12s. per week; in the fishing season, 14s. and 15s. Women receive for gutting and packing a full barrel, 7s. At this rate, with a sufficient supply of work, they might earn 5s. by a day’s work. The expense of curing a barrel of herrings is about 8s. besides the price of the fish.” (NSA, Vol. XIII, 1845, p. 236)

In the parish report for Banff, County of Banff, “the following table exhibits the state of the herring fishery, as regards the port of Banff alone, for the last five years.” (NSA, Vol. XIII, 1845, p. 41)

| 1831. | 1832. | 1833. | 1834. | 1835. | |

| No. of barrels cured, | 1759 | 1959 | 1265 | 938 | 631 |

| No. of boats employed, | 14 | 16 | 18 | 22 | 8 |

| No. of fishermen, | 56 | 64 | 12 | 88 | 32 |

| No. of women in curing and packing, | 41 | 46 | 48 | 60 | 21 |

| No. of coopers, | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 4 |

| No. of curers | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

It would be interesting to discover why figures dropped considerably in 1835!

Latheron, County of Caithness – “The herring being thus separated from the nets, are immediately landed and deposited in the curing box, where a number of women are engaged in gutting and packing them in barrels with salt.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 101)

Burntisland, County of Fife – “About 36 hands, including apprentices, are constantly employed as coopers; and about 60 females are occasionally employed in the curing of the herrings. The occupation is cold and disagreeable; but even this cannot warrant a pernicious practice that has long prevailed, of giving daily to those engaged in it, and some of these are young females, a considerable quantity of undiluted spirits.” (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 417)

Bressay, Burra, and Quarff, County of Shetland – “The curing of herring in Bressay employs about thirty women and children in the season… The manufacture of herring-nets now engages attention, and promises to be a useful employment.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 16)

Women also worked in the whale-fishing industry. In one company set up in Burntisland, County of Fife, from twelve to fifteen women were employed to clean the bone, compared with twelve oilmen and coopers. (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 418)

The Fish-Wives of Fisherrow

The parish report of Inveresk, County of Edinburgh, gives a fascinating insight into the lives of the fish-wives of Fisherrow, describing both their work and their demeanor. “They are the wives and daughters of fishermen, who generally marry in their own cast, or tribe, as great part of their business, to which they must have been bred, is to gather bait for their husbands, and bait their line. Four days in the week, however, they carry fish in creels (osier baskets) to Edinburgh; and when the boats come in late to the harbour in the forenoon, so as to leave them no more than time to reach Edinburgh before dinner, it is not unusual for them to perform their journey of five miles, by relays, three of them being employed in carrying one basket, and shifting it from one to another every hundred yards, by which means they have been known to arrive at the Fishmarket in less than 1/4 ths of an hour.” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 17)

They were very good at expressing themselves through language and gesture, and so were extremely gifted at selling. “Having so great a share in the maintenance of the family, they have no small away in it, as may be inferred from a saying not unusual among them. When speaking of a young woman, reported to be on the point of marriage. “Hout!” say they, “How can the keep a man, “who can hardly maintain herself?” As they do the work of men, their manners are masculine, and their strength and activity is equal to their work. Their amusements are of the masculine kind. On holidays they frequently play at golf; and on Shrove Tuesday there is a standing match at foot-ball, between the married and unmarried women, in which the former are always victors.” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 19)

Gathering kelp

Women also gathered and manufactured kelp. In Shapinshay, County of Orkney, “the summer months are occupied in burning kelp, which is the great manufacture of this country. The men almost of the whole islands, and many of the women, also exert themselves in this species of industry; and their joint efforts some seasons produce upwards of 3000 tons, which, at a moderate rate, brings near 20,000 l. to the inhabitants.” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 240) In Bressay, Burra, and Quarff, County of Shetland, “the manufacture of kelp in Bressay employs twenty or thirty boys and girls, who receive 9s. or more in the month, and have to work at least three hours every tide, by day or night. An overseer is employed, who receives at the rate of L. 2 per ton for his own wages and payment of the workers.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 16)

In Nigg, County of Kincardine, “to help their maintenance, the fisher-women at times, and also some women of the country, from the beginning of summer, go to the rocks at low tide, and gather the fucus palmatus, dulse; fucus esculentus, badderlock and fucus pinnatifidus, pepper dulse, which are relished in this part of the country, and fell them… The sea-ware, or bladder-fucus, grows up in three years on the rocks round the Ness and Bay chiefly, to a condition for being cut, dried, and burned into kelp. In 1791, 11 tons, of a fine quality, were made by 33 women, mostly young women, at 8 d. per day, with the direction of an overseer.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 207) However, in the later parish report for Nigg it was stated that “for many years past it has been discontinued, there being no demand for it. There was also, several years ago, a salt manufactory in the bay of Nigg, but it also has been given up. Lint was formerly sown and manufactured by private families in the parish, now there is no manufacture of the kind.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 209)

Conclusion

Looking through these excerpts on women in the farming and fishing industries, it is clear to see their common traits: strength, resourcefulness, dexterity and determination. They displayed a real fortitude and did not shirk hard work. This is illustrated again and again throughout the parish reports, and, we hope, is reflected in this series of posts on women in Scotland. In our next post, we will continue looking at other kinds of work undertaken by women, some of which may surprise you!