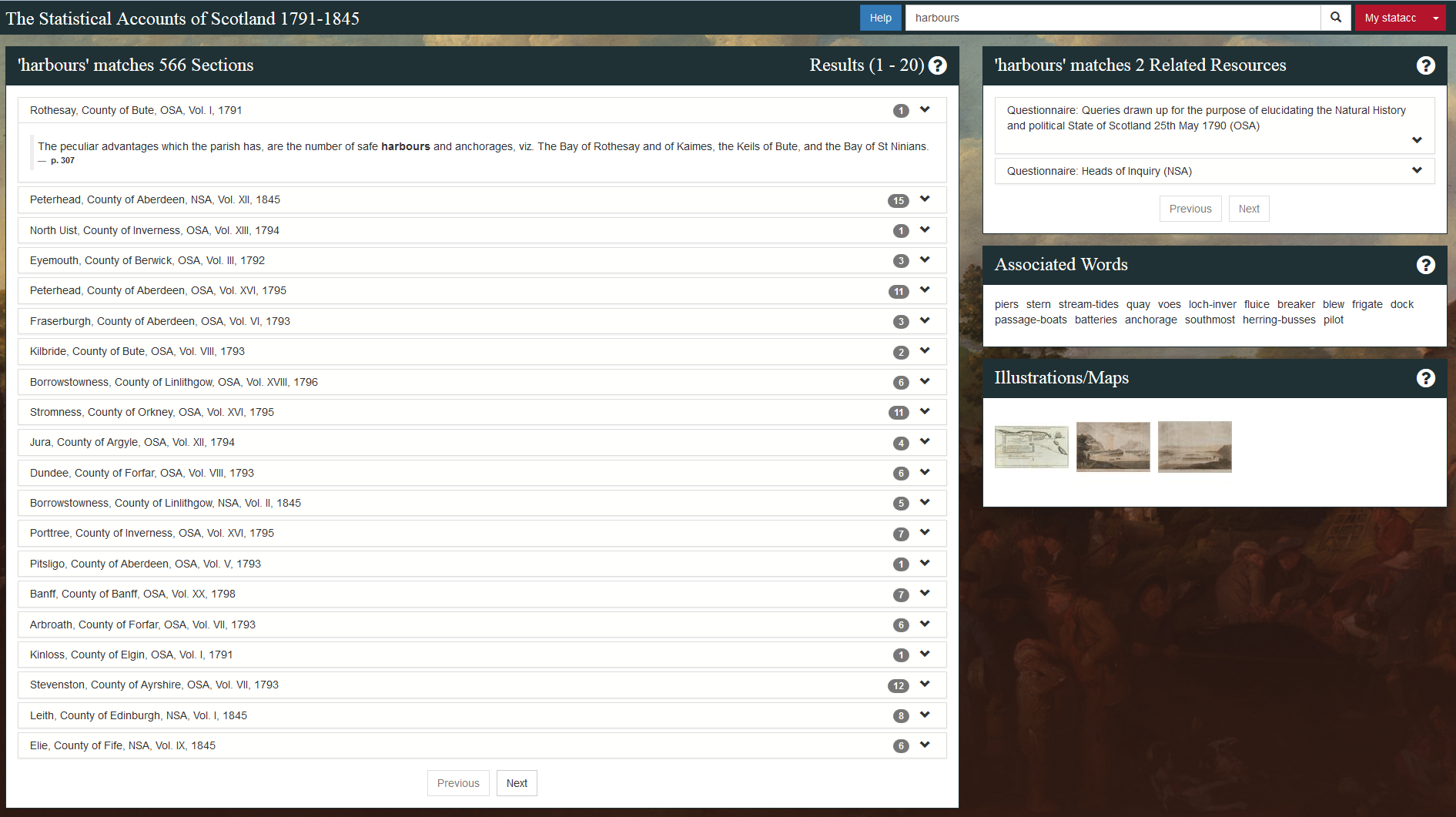

This is the third, and last, post on Scotland’s music and dance. This time we look at musical education, music in religious contexts and changes in the attitudes to music.

Musical education

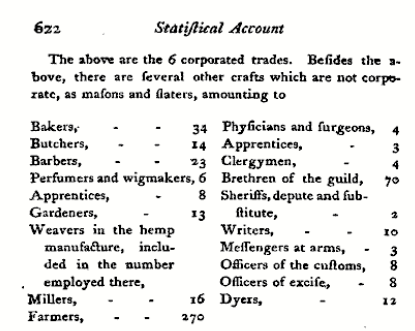

There are many mentions of music, more specifically church music, being taught in Scottish schools, along with the core subjects of English, writing and arithmetic. These include the parishes of Monkton and Prestwick, County of Ayrshire (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 401), Calder Mid, County of Edinburgh (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 378) and the Merchant Maiden Hospital in particular in Edinburgh (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 724). There is a particularly interesting breakdown of what was taught, for how many lessons and the fees to be paid in a lady’s school in Arbroath, County of Forfar. (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 103)

In Ancrum, County of Roxburgh, “the parish schoolmaster has the maximum salary, the legal quantity of garden ground, and a good house, consisting of four apartments. He also receives the annual interest arising from a sum of L. 50, which was left by a former resident in Ancrum, for behoof of the parish teacher, on the condition that he gives instruction in church music to some of the poorer children in the village.” (NSA, Vol. III, 1845, p. 250) In Edinburgh, there was a school attached to a workhouse, “in which nearly 200 pauper children, inmates of the work-house, are taught reading, writing, arithmetic, grammar, geography, sacred music, and religious and general knowledge, and attend a Sabbath evening school.” (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 748) Both these examples show how important it was believed for all classes to have some level of instruction in church music. A music education was believed to increase spirits, as well as intellectual character. “Instead of the noisy, and not unfrequently demoralizing gymnastic exercises in which they used to excel, music has of late years been successfully cultivated by the operatives, as their instrumental band sufficiently testifies…” (NSA, Vol. V, 1845, p. 710)

However, in some quarters, there was felt to be a lack of music education, which was considered of real detriment to parishioners. In the parish report for Ellon, County of Aberdeen, the following remark was made:

“It is easy to see, also, how poetry, and its sister art of music, for the employment of which in the work of education we have the authoritative example of God himself, might be brought to blend in entire harmony with the elements above-mentioned, in moulding, according to the Scriptural pattern, the dispositions and principles of the rising generation. These departments have heretofore been all but neglected; and hence are we supplied with another cause of the inadequate moral and religious tendencies of the system of education now in use.” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 937)

In some areas, however, music schools were established, such as the singing school at Blackfriars or the College Church in Glasgow. “Indeed, considerable exertions were used by the session and town-council to obtain a properly qualified man. The Principal of the University’s name appears on the list of the committee appointed to find a music-master; and a desire is expressed to encourage not merely vocal but instrumental music.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 931) In St Andrews, “a music-master and dancing-masters, of approved character, [taught] during the winter months.” Dancing schools were also set up in Scotland. In Stromness, County of Orkney, “in 1793, a dancing-master opened a school, obtained 40 or 50 scholars, and drew L. 50 in four months.” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 468)

Music in religious settings

It is clear that church music was considered a very important part of people’s education. This is underscored by the fact that many complaints were made in the parish reports about congregations not being able to sing in tune! At the presbytery of Inchinnan, County of Renfrew, the doxology, which was ordered to be sung every Sunday, was omitted. “It was argued in defence, that none of the people would join in such music, and that the minister and preceptor being the only performers, and sometimes both of them alike destitute of a musical ear, the effect was bad, and the discord intolerable.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 131)

As a result, in several parishes there was a concerted attempt to improve church music. In Monymusk, County of Aberdeen, Sir Archibald Grant, as well as introducing turnip husbandry in Aberdeenshire, “procured a qualified teacher for the congregation, and [took] an active and leading part among the singers himself; whence this, like his improvements in agriculture, gradually overcoming the prejudices of the people, soon made its way through the surrounding country.” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 461)

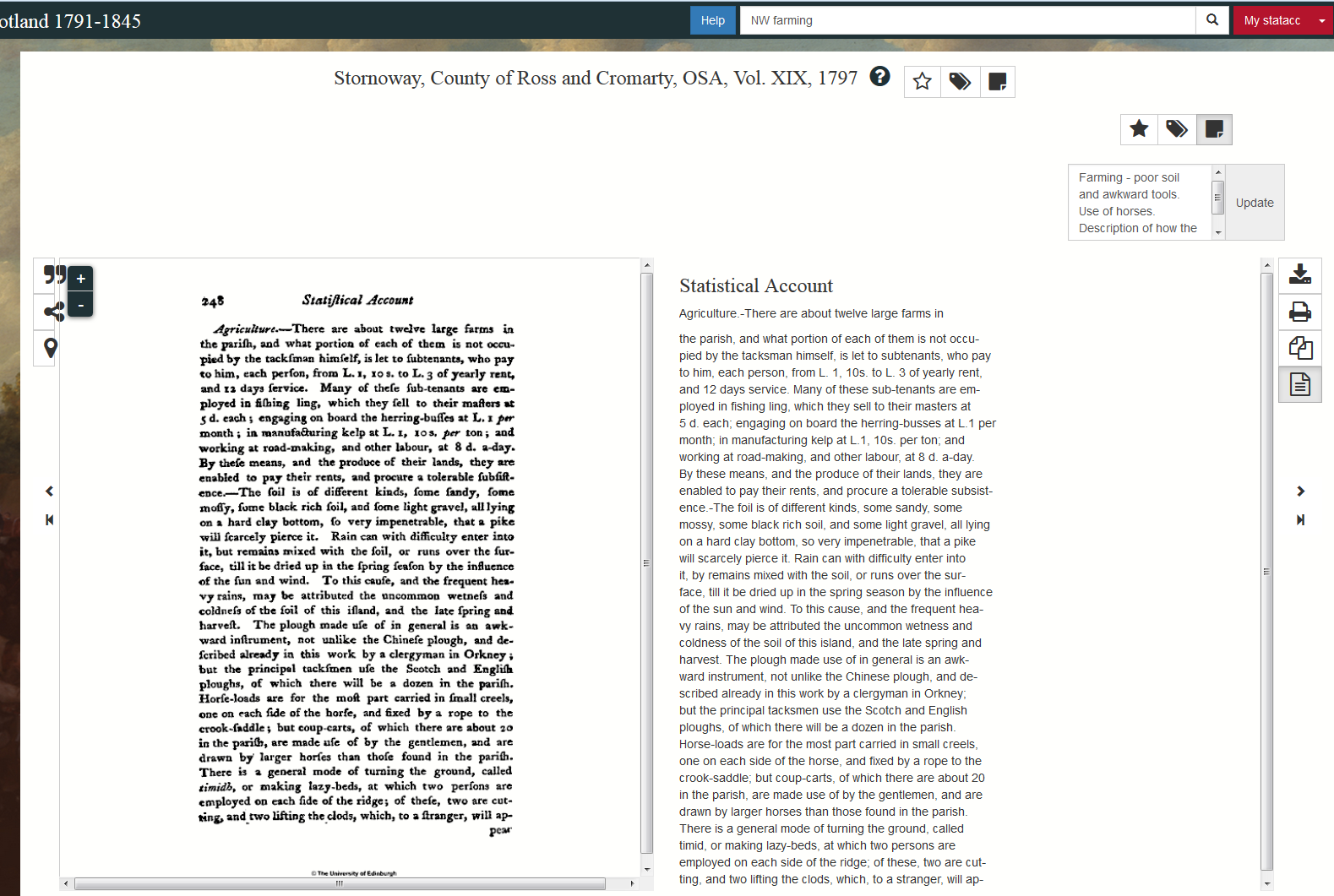

Angel playing bagpipes in the Thistle Chapel, St. Giles, Edinburgh. By Kim Traynor (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

In Dalziel, County of Lanark, the improvement in church singing was also judged a success. “Understanding music himself, and delighting in having that part of the church service properly conducted, he [the writer’s father] got masters to teach the young connected with the church, and then drilled them himself, by meeting with them in the church once a week. The consequence of this training was, that, from being one of the worst singing congregations in the district, they became the very best,–the admiration of all strangers, and a model for the imitation of their neighbours. The taste for church manse in the parish from that date, has never died out, is still lively.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 465)

However, it was a harder task in the parish of Peterhead, County of Aberdeen. “Attempts have been made to improve the church-music both in the Established Church and in the Episcopal chapels; but the improvement is very slow, and from what-ever cause it may proceed, a taste for music is much less frequent on the sea-coast in Buchan than in the higher parts of the county.” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 590)

Dancing may not be part of church services, but it is represented in at least one place of worship, though it is the Devil who dances! In Roslin Chapel, County of Edinburgh, on the side of one of the arches there is a series of figures believed to be representing the Dance of Death. “Commencing at the top of the arch, and descending to the right, the figures, which can be recognized, are, a king, a courtier, a cardinal, a bishop, a lady admiring her portrait, an abbess, and an abbot; and each of these is accompanied with a figure of death dancing off with his prey. Again, commencing at the top of the arch, and descending to the left, the following figures are quite distinct: a farmer, a husband and wife, a child, a sportsman, a gardener and spade, a carpenter, and a ploughman. Each of these also is accompanied by a figure of death, carrying off the individual”. (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 345)

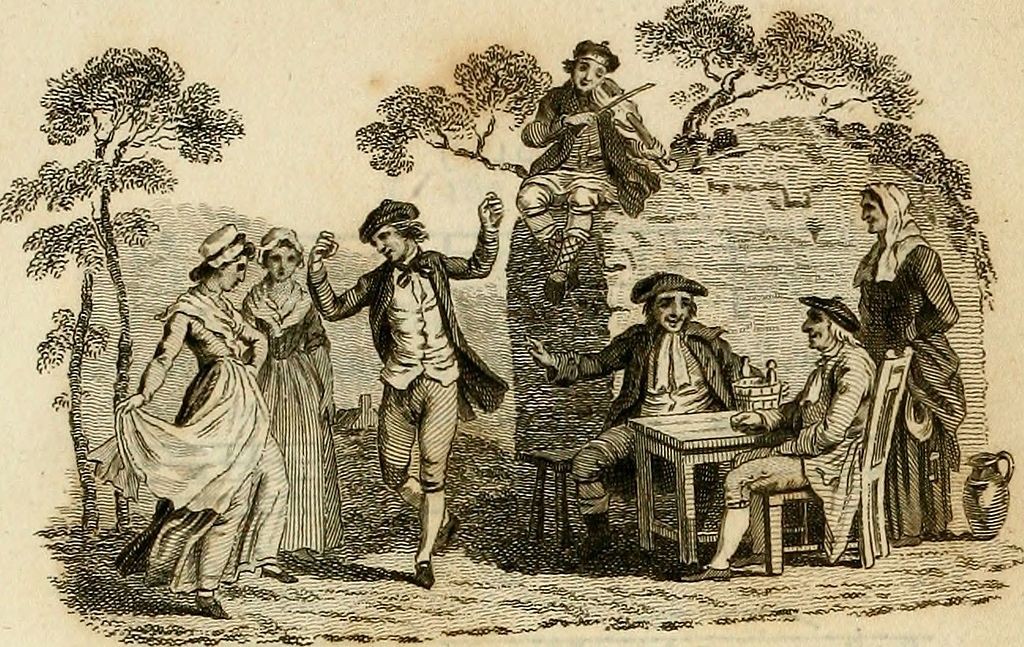

Marriages and funerals

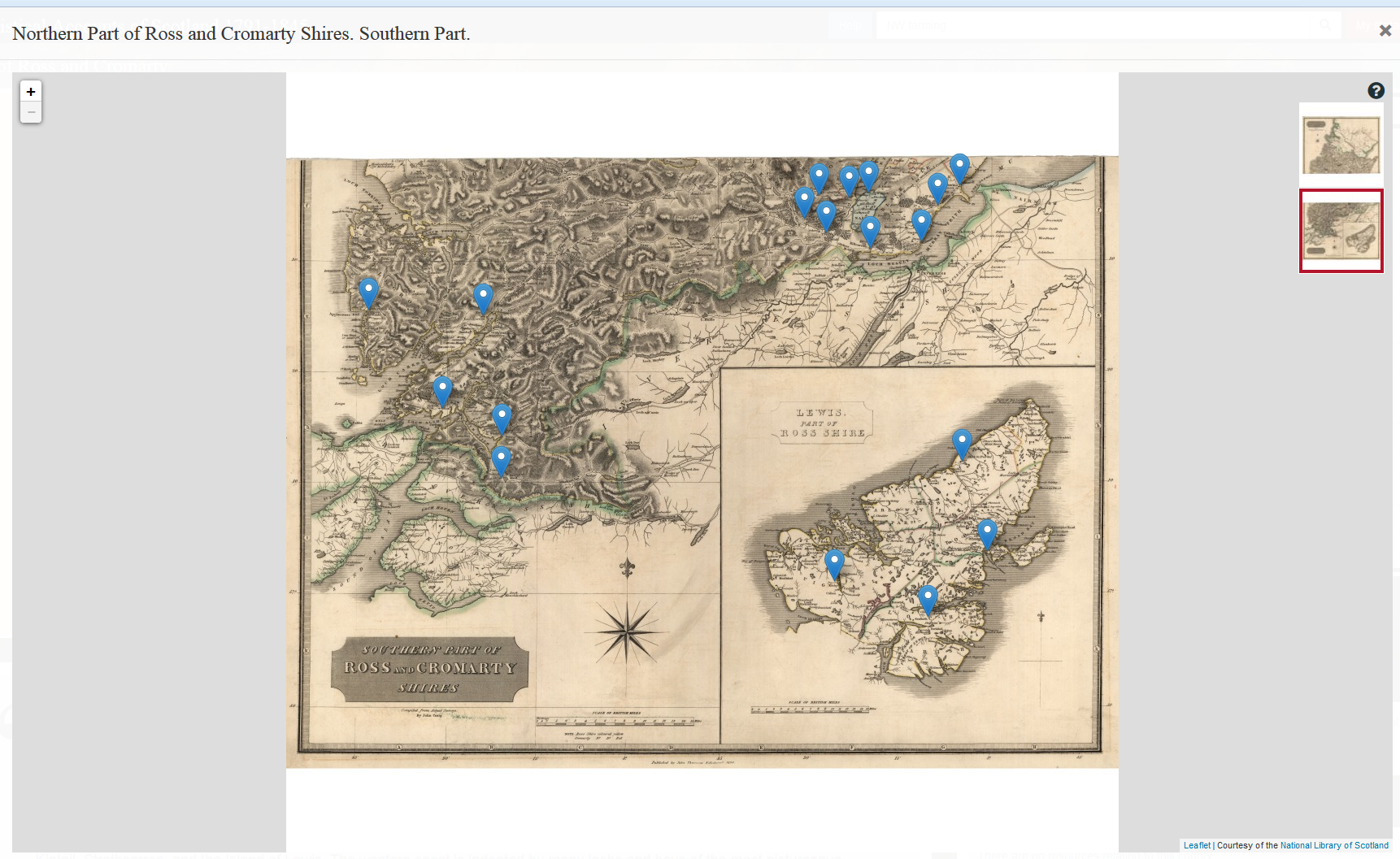

Music has, for a long time, been a part of religious ceremonies, particularly marriages and funerals. In Lismore and Appin, County of Argyle, either the bagpipes or violins were played at weddings, depending on the area. “Marriage ceremonies are always performed in the church, particularly in Lismore; and the only music that is used, either at, weddings or balls, is that of the bagpipe. The violin is used in Appin and Kingerloch on such occasions.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 245) In Moy and Dalarossie, County of Inverness, “on marriage occasions, a bagpipe always precedes the parties on their way to the church, and in the evening there is a dinner given gratis, and drinking afterwards, for which each pays a certain sum. There are always music and dancing. Up on the whole, however, the character of the people is very moral.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 107)

The Highland Wedding, David Allan (Scottish painter 1744-1796), 1780. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:PKM [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Changes in attitudes to music and dance

Having read about the importance of music and dance in Scotland over the last few blog posts, you may be very surprised to hear that many parishes in the Statistical Accounts reported that inhabitants were actually loosing their love of music. This includes the parish of Tongue, County of Sutherland, where “the taste for music, dancing, and public games, is much on the decline, and few or no traces are to be seen of the poetic talent and sprightly wit for which their ancestors, in common with most Highlanders, were distinguished.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 177)

In the county of Peebles it was reported that “song is scarcely ever to be heard; that a ploughman seldom enlivens his horses by whistling a tune; and that, although the scenery is so purely pastoral, the sound of a pipe, or flute, or cow-horn, or stock in horn, or even of a Jew’s harp, is a rare occurrence in traveling through it.” (NSA, Vol. III, 1845, p. 179)

In the parish report for Auchterderran, County of Fife, one reason given for this waning was that people equated song and dance with immoral excess. “Among the infinite advantages of the Reformation, this seems to have been one disadvantage attending it, that, owing to the gloomy rigour of some of the leading actors, mirth, sport, and cheerfulness, were decried among a people already by nature rather phlegmatic. Since that, mirth and vice have, in their apprehension, been confounded together.” (OSA, Vol. I, 1791, p. 458)

This decline was bemoaned by many report writers, such as the Rev. Mr Alexander Molleson of the parish of Montrose, County of Forfar. “Instrumental music has been, for many years past, much neglected. Public or private concerts are rare. This is the more to be regretted, as music is a very innocent, cheerful, and rational amusement, and if more cultivated, might divert the attention from other objects, which injure the health, or destroy the morals of the people.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 48)

In Duirinish, County of Inverness, “it is rare to hear a song sung, and still rarer to hear the sound of pipe or violin. Each family confines itself to its own dwelling, or, if a visit is paid, the time is spent in retelling the silly gossip of the day. People certainly may be far more beneficially employed than the old Highlanders used to be yet we conceive the change in their habits to be a subject of regret on various grounds…” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 358)

Attitudes to music and dance have also changed in other ways. One interesting letter was written by William Creech who, in the Appendix for the Edinburgh parish report, compared different aspects of life from one time to another, including changes in correction houses, the definition of “a fine fellow” and concerts:

“In 1763-The weekly Concert of music began at six o’clock.

In 1783-The Concert began at seven o’clock; but it was not in general so much attended as such an elegant entertainment should have been, and which was given at the sole expense of the subscribers.

In 1791-2, The fashion changed, and the Concert became the most crowded place of amusement. The barbarous custom of saving the ladies, (as it was called), after St. Cecilia’s Concert, by gentlemen drinking immoderately to save a favourite lady, as his toast, has been for some years given up. Indeed, they got no thanks for their absurdity.”(OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 617)

Importance of music and dance to Scotland

Even though such changes in attitudes were reported, music and dance have stood the test of time in Scotland. From social gatherings to religious settings, the Scots have used song and dance to express themselves, as well as find enjoyment in their lives. It has become an important part of the country’s identity. Exploring this topic in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland gives these musical traditions real meaning and so helps keep them alive.