This is the second post on Scotland’s languages. This time we look more closely at the languages spoken throughout the parishes. As can be gleaned in the last blog post, at one point the majority of Scots spoke Gaelic, or Erse as this was called in some of the parish reports. According to the authors of the Statistical Accounts, Gaelic was more widely spoken in many parishes. But there were also areas of Scotch or Scots speakers, with English beginning to make strong inroads.

Predominantly Gaelic-speaking parishes

There were many parishes where most inhabitants spoke Gaelic, including:

- Barvas, County of Ross and Cromarty (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 147);

- Moy and Dalarossie, County of Inverness (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 499);

- Applecross, County of Ross and Cromarty (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 102)

- Gairloch, County of Ross and Cromarty – “The Gaelic is the prevailing language in this, as well as in several other corners on the West coast” (OSA, Vol. III, 1792, p. 93);

- Inverary, County of Argyle – “The language generally spoken is the Gaelic. Among the agricultural labourers, it is almost exclusively used; and as many of them, for various reasons, remove from the country into the burgh, they naturally continue to speak their mother tongue, and to teach it to their children.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 27).

Brown, William Beattie; Coire-na-Faireamh, in Applecross Deer Forest, Ross-shire; 1883-84. Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/coire-na-faireamh-in-applecross-deer-forest-ross-shire-186783

However, this situation was beginning to change. If you look at the parish reports for Gigha and Cara, County of Argyle, you can see the differences in language use even between the Old and New Statistical Accounts of Scotland.

“The language of the common people is Gaelic, but not reckoned the purest, on account of their vicinity, to Ireland, and intercourse with the low country, by which many corruptions have been introduced into their phraseology. They understand English, and several speak it well enough to transact business; but very few of them can understand a connected discourse in that language.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 65)

“English, however, is much better understood by young and old than it was forty years ago, but there are not above ten persons in the parish who do not understand and speak Gaelic.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 401)

By the time of the New Statistical Accounts, in practically all of the parishes English was increasingly understood and spoken. It is always interesting when figures, even approximations, are provided. In Southend, County of Argyle, “the language generally spoken by two thirds of the people is Gaelic; but, from the establishment of schools and the intercourse with Campbelton, and the Lowland districts of Scotland, the English language is beginning to be universally understood. Families who understand Gaelic best, 210; English best, 145.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 431)

We will be looking at the rise of the English language in the next post.

Predominantly Scotch/Scots-speaking parishes

Scots is a Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and some areas of Ulster. It is itself “a dialect of the Dano-Saxon, which was brought from the other side of the German Ocean, by the Danish invaders of the ninth and eleventh centuries”. (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 226) Here are some examples of parishes which were predominantly Scots-speaking. Again, we can see that in many cases other languages have also left their mark.

- New Spynie, County of Elgin (OSA, Vol. X, 1794, p. 637)

- Cromarty, County of Ross and Cromarty – “The language of all born and bred in this parish, approaches to the broad Scotch, differing, however, from the dialects spoken in Aberdeen and Murrayshire; this being one of the three parishes in the counties of Ross and Cromarty, in which, till of late years, the Gaelic language, which is the universal language in the adjacent parishes, was scarce ever spoken. There has been a considerable change, of late years, in this respect, among the inhabitants here; the Gaelic having become rather more prevalent than usual.” (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 254) This was attributed to Gaelic-speaking people coming to work in the parish.

- Kirkmichael, County of Ayrshire – “The language is a mixture of Scotch and English, without any particular accent. In this district, as in every other, there are certain provincial words and phrases peculiar to itself.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 111)

- Drainie, County of Elgin – “The only language here is Scotch; but the pronunciation is gradually approaching nearer to the English. Gaelic is not spoken nearer than 20 miles; and very few

of the names of places here seem derived from it.” (OSA, Vol. IV, 1792, p. 87) - Boharm, County of Banff – “The Scotch is the only language spoken in the parish; but, with a few exceptions, the names of the places belong to the Erse tongue.” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 362)

- Tannadice, County of Forfar – “The broad Scotch is the only language spoken here. Some of the names of places are Gaelic, and others of Gothic origin; although the former seems to abound most.” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 380)

- Kinfauns, County of Perth – “The language of this parish and corner is Saxon, intermixed with Scottish words and expressions; attended, however, by little or no provincial accent or dialect. Though this part of the country is not at a great distance from the Highlands, yet neither Gaelic words nor accent are known amongst the natives below Perth. Very few names of places are Erse; but great number are Scotch or Saxon.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 223)

- Canisbay, County of Caithness – “The Scotch, with an intermixture of some Norwegian vocables, is the only language spoken in the parish… There is scarcely a place in the whole parish, whose name is not of Norwegian derivation.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 162)

- New Machar, County of Aberdeen – “The common people speak the Scotch language, and in what is commonly called, and well known by the name of, the Aberdonian Dialect.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 470)

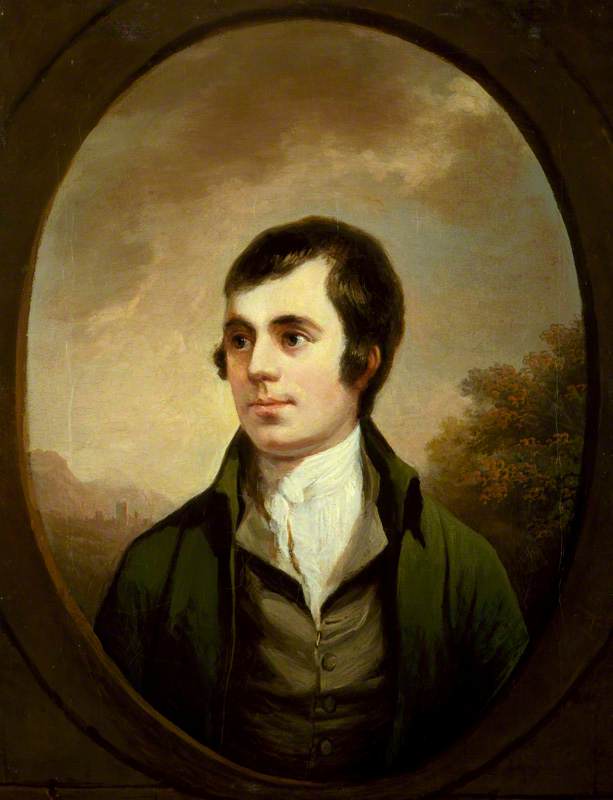

Nasmyth, Alexander; Robert Burns; 1821-22. National Portrait Gallery, London; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/robert-burns-157341

In some parish reports, particular Scots pronunciation was remarked upon. In Gamrie, County of Banff, “the language spoken in this parish is the Scottish, with an accent peculiar to the north country. There is no Erse.” (OSA, Vol. I, 1791, p. 477) In Dron, County of Perth, “the language spoken here is Scotch, with a provincial accent or tone; the pronunciation rather slow and drawling, and apt to strike the ear of a stranger as disagreeable.” (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 478) Scots spoken in the county of Fife also had its own pronunciation. In Carnock, County of Fife, “the language now generally spoken in this district, is the broad Scotch dialect, with the Fifeshire accent, which gives some words so peculiar a turn, as to render the speaker almost unintelligible to the natives of a different county.” (OSA, Vol. XI, 1794, p. 496) In St Andrews and St Leonards, County of Fife, “the language of this parish is the common dialect of the Scotch Lowlands. The Fifans are said, by strangers, to use a drawling pronunciation, but they have very few provincial words.”(OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 215) Specific examples of pronunciation will be given in the next post on Scotland’s languages.

Predominantly English-speaking parishes

What is particularly interesting to note about the predominantly English-speaking parishes is that, for the most part, they do not actually border England! (Read the next post to look at possible reasons why.) Again, there are influences from other languages, such as Gaelic and Scots, and Norse in the Shetland Isles.

- Cushnie, County of Aberdeen – “English is the only language now known in the parish, the Gaelic having ceased to be understood.” (OSA, Vol. IV, 1792, p. 177)

- Ardersier, County of Inverness – “The language generally spoken in the village, which contains three-fourths of the population of the parish, is English. In the interior, Gaelic prevails. But, from recent changes in the lessees of farms, and from the new occupants possessing little of the Celtic character, it may be fairly stated, that the Gaelic has lost, and is losing ground.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 472)

- Newbattle, County of Edinburgh (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 70)

- Broughton, County of Peebles – “The language spoken here is English, with the Scotch accent.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 158)

- Kirkconnell, County of Dumfries – “only the English language is now spoken here, as in the rest of Nithsdale, with considerable purity, excepting chiefly a few old Scotch, or rather obsolete Saxon words, that now and then occur; and in a plain, easy, manly style of pronunciation, without any of those grating peculiarities of provincial accent, that mark the dialect of some of the adjoining counties. With the small exception, of one from England, and another from Ireland, the inhabitants are all natives of Scotland.” (OSA, Vol. X, 1794, p. 447)

- Portpatrick, County of Wigton – “English is spoken in this parish, with less of provincial accent and less mixture of Scotch than in the more central and populous districts of Scotland.” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 145)

- Section on the county of Shetland from volume 15 in account 2 – “The language is English, with the Norse accent, and many of its idioms and words.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 156)

Here, we should mention that there seems to be some confusion between the English language and the Scots dialect. In some quarters, Scots is seen as a dialect of English, or even “English or Saxon, with a peculiar provincial accent” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 193), instead of it being a language in its own right. This makes it a little difficult to identify those parishes speaking English and those speaking Scots. Examples include:

- Bellie, County of Elgin – “The Gaelic tongue, however, has long disappeared in this part of the country; the language, in general, being that dialect of English common to the North of Scotland; though, among all persons who pretend to anything like education, the English language is daily gaining ground.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 264)

- Luss, County of Dumbarton -“The language now universally spoken by the natives of the parish is the English language, or rather the provincial Scotch dialect.” (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 162)

- Speymouth, County of Elgin – “The language here spoken is the English, if the broad Scotch that is spoken throughout the greatest part of Murray, Banff, and Aberdeenshires, be thought entitled to that name. Erse is not the common language within 20 miles of us.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 406)

- Keith, County of Banff – “In this parish, and in all the neighbourhood, the language spoken is the Scotch dialect of the English language.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 423)

Language differences within parishes

As well as language differences between parishes, there are differences within parishes. In the parish of Luss, County of Dumbarton, “south from Luss, English, and north from it the Gaelic, is the prevailing language.” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 266) Here are some other inter-parish variations:

- Keith, County of Banff – “All the old names of places are evidently derived from the Gaelic, which language is generally spoken in a detached corner of the parish, by a colony from various districts of the Highlands; who being indigent, and supported by begging, or their own alertness, are allured there by the abundance of moss, and the vicinity of a very populous and plentiful country.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 423)

- Little Dunkeld, County of Perth – “In that part of the parish which is below lnvar, the people speak the Scottish dialect of the English, and are not distinguished by any perceptible shade of character from the inhabitants of the low country parishes around them. The rest of the inhabitants (more than three fourths) are Highlanders, who speak a dialect, not perhaps the purest, of the Gaelic. They have all a strong attachment to their native tongue; many speak English with tolerable case, and the youth, by means of the charity schools, can write it with rather more propriety, and copiousness than those of the low country part of this parish, who are very all situated with respect to schools.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 369)

- Dowally, County of Perth – “It is curious fact, that the hills of King’s Seat and Craigy Barns, which form the lower boundary of Dowally, have been for centuries the separating barrier of these languages. In the first house below them, the English is, and has been spoken; and the Gaelic in the first house, (not above a mile distant), above them.” (OSA, Vol. XX, 1798, p. 490)

- Edenkillie, County of Elgin – “In the lower part of the parish, the Scotch dialect of the English language is only spoken; but, in the upper part, the Gaelic is still much in use. About 50 years ago, the minister preached the one half of the day in English, and the other half in Gaelic.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 566)

- Strathdon, County of Aberdeen – “The language spoken is English, or rather broad Scotch, excepting in Curgarff. The people there, especially in the upper part of that district, speak also a kind of Gaelic; but that language among them is much on the decline.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 183)

- Monzie, County of Perth – “This parish being situated on the borders of the Highlands, and having much intercourse and connection with the natives, we need not be surprised to find that the Gaelic is spoken in the back part of it, and the old Scotch dialect in the fore part, pronounced with the Gaelic tone and accent. There are, however very few persons in the whole parish, who do not either speak or understand Gaelic.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 251)

- Dunkeld, County of Perth – “The English language is spoken in Dunkeld. In Dowally, with the exception of 110 persons, English is spoken with fluency, but they prefer Gaelic. Gaelic is still preached, and it is taught, along with English, at school.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 989)

- Crieff, County of Perth – “The people speak the English language in the best Scotch dialect: although the Gaelic be commonly spoken at the distance of three miles north, of four west from Criess, yet no adult natives of the lowland part of the parish can either speak or understand it. They have not even contracted the peculiar tone of that language, by their intercourse with the numerous Highland families now residing in the town. Many indeed of these understand no other language but the Gaelic, and their children born in Crieff speak that alone for a few years as their mother-tongue.” (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 601)

Conclusion

It has been very interesting to discover the language similarities and differences between parishes and even within parishes. It is clear that, even though parishes were predominantly Gaelic, Scots or English speaking, other languages were influencing what was being spoken. In the next post, we will look at the concept of language purity and, conversely, corruption, as well as specific examples of pronunciation found in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland.

Fascinating blog, with some tantalising details, well done. On the choice of predominantly Gaelic parishes you chose ‘predictable’ places in the West – it would have been more enlightening to compare, for example Canisbay in Caithness as a parish with ‘no Gaelic’, to another Caithness parish such as Latheron or Halkirk, both showing just the kind of advance of English by the New SA you discuss, but (no doubt to some people’s surprise today) even by the NSA still recording Gaelic as predominant among the population.

Two minor points – Ulster isn’t in Northern Ireland, the opposite is the case – Northern Ireland is in Ulster. (NI comprises 6 of the 9 counties which make up Ulster).

And it would just look more natural to write Gaelic (or ‘Erse’ as many of the writers for the Statistical Accounts called it). It’s an archaic term, not in use today.

Thank you though.

The online SAs are a very useful resource.

Thanks very much for your comment. I’m glad you enjoyed the post. It is an interesting point you make with regards to the comparison of parishes. We will think about that for a future post. Apologies for the Ulster mistake. We have now corrected this.

It is great to hear that you find the online accounts useful. It would be great to hear how you have used them for research.

[…] mentioned in an earlier post (Scotland’s languages: Gaelic, Scots and English), those parishes where English was gaining ground were not necessarily anywhere near the English […]