Last week I had the pleasure of visiting the Lothian Family History Society, who meet just outside Edinburgh in the Lasswade Centre. It was a lovely opportunity to meet some of the people who have interests in the Statistical Accounts, and another chance for me to delve into the content of the Statistical Accounts and explore the kind of interesting descriptive details they contain. A great deal can be gleaned about our ancestors in the late 18th and early 19th century through these reports. I thought it would be fun to focus on the parish in which we were present, so had a look at the two Lasswade accounts.

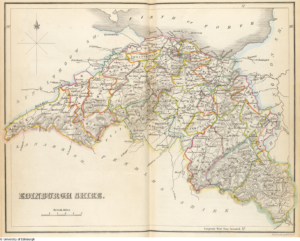

Lizars Map of the County of Edinburgh, published with the Second Account (vol 1)

The name Lasswade “signifies a well-watered pasture of common use”,* according to the Rev. M. Campbell MacKenzie, who complied the parish report for the second account. And well it might, given the position of Lasswade directly on the river Esk, in what is now the green belt around Edinburgh.

In the first account, we learn that the population in 1791 was more than 3000 inhabitants, so the village was a good size. There is plenty of work: agriculture is thriving and bleachfields, coal mining and paper making are the main (non-agricultural) industries with 260 people employed in the latter two. Around 150 women are employed as coal bearers underground. Only 50 people were claiming poor relief: the income from the church collection and fees (for weddings etc.), we learn, was supplemented by the heritors of the village: “This mode they prefer widely to an assessment, a measure which ought always to be avoided, if possible, as it never fails to increase the number of claimants. There is a laudable spirit in the common people of this country, which keeps them from applying for aid out of the poor funds, so long as they can do anything from themselves. This arises from the apprehension that these funds depend for their supply solely on the voluntary contributions at the church door.” One of the common pastimes, the minister notes, is gardening: “the attention of the gardener is chiefly directed to the cultivation of strawberries, than which he has not a surer or more profitable crop […] It may be observed that it was in this parish that strawberries were first raised in any quantities for the public market.” So one of Lasswade’s claims to fame might be as the home of the commercially grown strawberry!

Half a century later, in 1841, Lasswade had a population of 5022: it had not quite doubled in size, but it had certainly increased. The growing parish had also been divided into two by this point, at least quoad sacra (in a spiritual sense) but ‘temporal matters’, quoad civilia, were still common to both. Manufacturing in the area is now dominated by paper (c. 300 people) and carpets (c. 100 people). But despite the growing populace, and the 75 on the roll, and a considerable number of people who receive occasional assistance. There is an assessment, so the Heritors have evidently given up on their custom of supplementing the Church collections, which is perhaps unsurprising given the 50% increase in claimants. Gardening continues: “vegetation is both early and luxuriant” and by this time, we learn, the green charms of the area have rendered “the village of Lasswade a place of considerable resort to the inhabitants of Edinburgh and Leith numbers of whom annually spend the summer months in this delightful locality.” Perhaps in keeping with its growing reputation as a notable locale in the area, the Lasswade report in the second account devotes a significant proportion of its pages to discussion of the lives of ’eminent characters’ and fascinating antiquities. The former include the poet William Drummond of Hawthornden, Mr Clerk of Eldin, author of an important essay on naval tactics, and the late Lord Melville. The latter feature notable sights such as the caves below Hawthornden which could hold upwards of 60 men and were used to conceal troops during “the contest between Bruce and Baliol” and “the famous sycamore tree which is called the fours sisters and is about 24 feet in circumference at the base. It was under this tree that Drummond the poet was sitting when his friend Ben Jonson arrived from London, and hence it is also called Ben Jonson’s tree.” Such points of historical interest might appeal to the kind of metropolitan visitor that Lasswade was now attracting, and – like the second account report for neighbouring Roslin, which is given over almost entirely to a description of the ornamental chapel – it reads more like a tourist guide than a survey of the people and the land!

*All quotations in this post are taken from the Lasswade parish reports, which appear in the OSA, Volume 10 p. 227 – 288 and the NSA Vol 1, p. 323 – 337