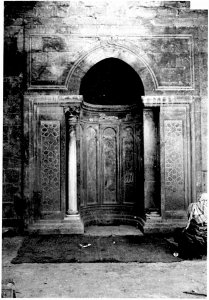

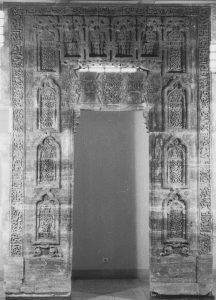

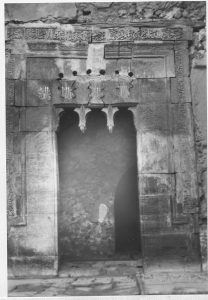

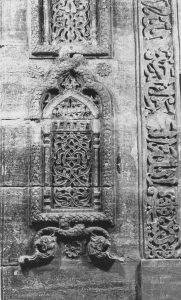

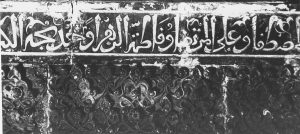

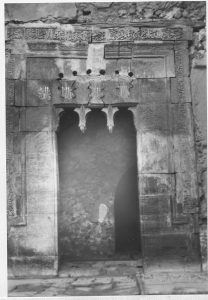

Aleppo. Madrasa al Zahariyeh

The aim of our PhD thesis digitisation project is to make available the unique research of the University of Edinburgh. This research has a greater significance when, within the pages of the theses, we uncover photos of places and buildings that no longer exist; our collection becomes important for the future preservation of world cultural heritage.

In the past year a great deal of research has been undertaken on collecting images of Palmyra that date to a period before it was damaged (in 2015), as well as of other Syrian archaeological sites.[1] Much of this work depends upon using archival images of the areas in question, often from personal collections. Such images can aid with digital, and perhaps eventually physical, reconstructions. Some of the items that we have scanned as part of our thesis digitisation project, and that are now available on ERA (Edinburgh Research Archive, by ‘Abbū ,1973 and Al-Janābī 1975), also include images of buildings destroyed or damaged in past few years, not just in Syria but also in Iraq.

In the last year much media attention was given to those buildings and archaeological sites which date to the pre-Islamic era, such as Palmyra. However, many early Islamic structures and sites have also been subject to destruction, although these are often less well publicised. Furthermore due to the turbulent situation in the areas in question it can be rather difficult to ascertain if a building has been destroyed or when damage took place.

Although there may be little that can be done to prevent this destruction, we can ensure to properly look after and maintain documents relating to the artefacts in question and make them publicly available so that these can be used for digital reconstructions. This blog will focus, in particular, on those early-Islamic buildings destroyed in 2013/14 in Aleppo (Syria), Samarra (Iraq), and in Mosul (Iraq).

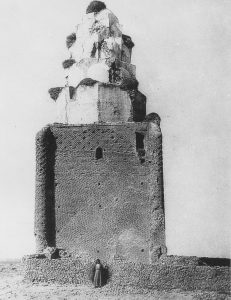

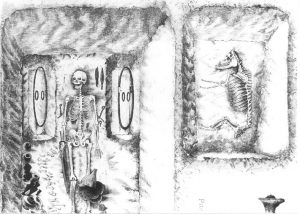

Mosul. Mausoleum of al-Imam Yayha ibn al-Qasim.

The two theses mentioned above and dating from the 1970’s, contain images of buildings in these areas: The Ayyubid domed buildings of Syria by ‘Ᾱdil N. ‘Abbū (1973) and Studies in Mediaeval Iraqi Architecture by Ṭāriq Jawād Al-Janābī (1975). Both theses present a catalogue of monuments. In the first the Ayyubid dynasty is examined over the period from AD 541-1260, focusing on the areas of Damascus and Aleppo. The second thesis covers the time period between the 6th and the 8th centuries AD and areas ranging from Baghdad, Wasit, Mosul, Al-Kifil, Kufa, Basra and Amadiya. The contents of the first chapter are wide ranging, reading: the Saljuq period, the Abbasid Caliphate during the 6th to 7th centuries A.H., the Atabikids of Iraq, the Mongol invasion and the Ilkhanid Period, the Jalairids.

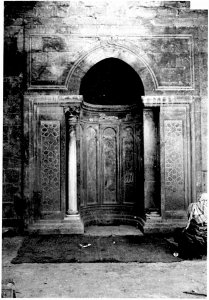

Aleppo. Madrasa al Zahariyeh

The types of monuments discussed in both works include: madrasas (koranic schools; some of these built at the request of the Sunni madhab),[2] turbas, mosques, ribats, minarets, palaces and mausolea.

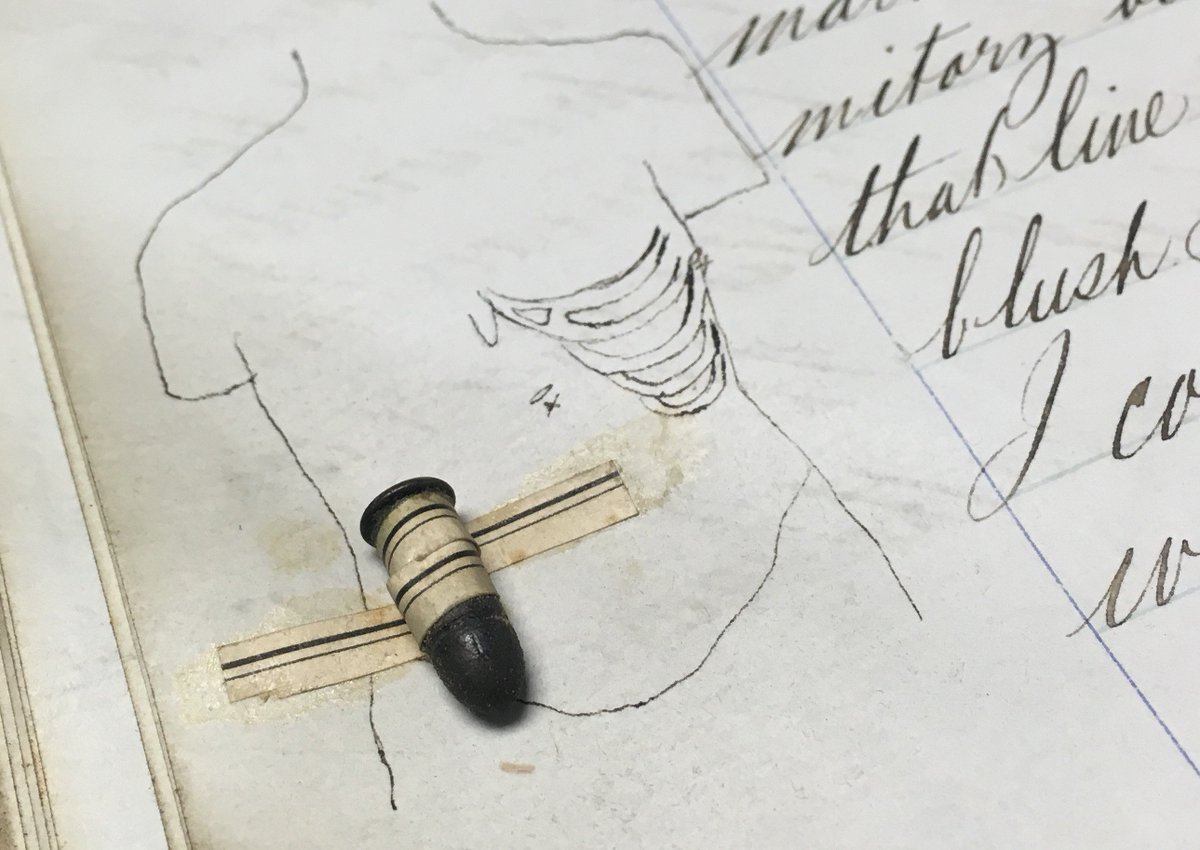

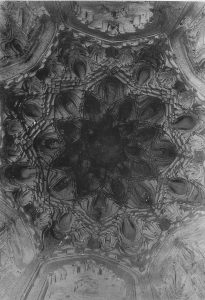

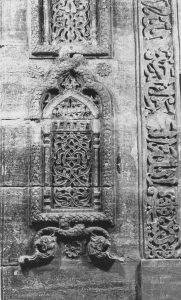

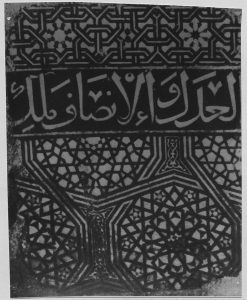

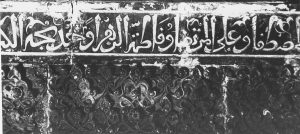

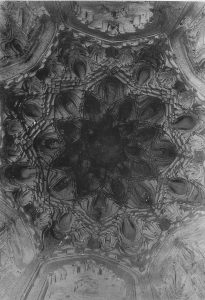

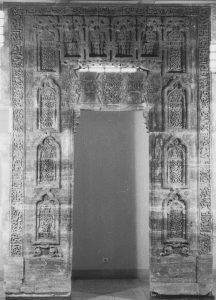

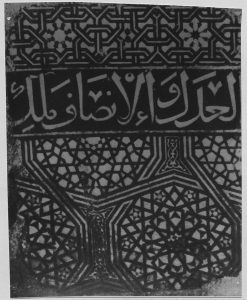

These works are so important for preserving the past because they include many good quality photographs, including of the type of minor decorative details that are difficult to reproduce accurately, such as wood and stucco windows and façades.[3]

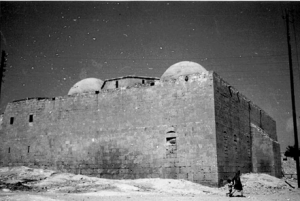

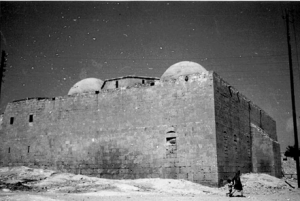

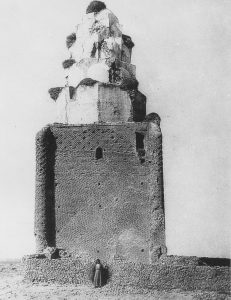

Samarra. Mausoleum of Imam Dur.

Mosul. Mausoleum of Imam Bahir.

Mosul: mausoleum of Imam Bahir.

Mosul. Mausoleum of Imam Bahir.

To highlight the importance of these works a selection of photos from the theses are included, depicting buildings that are now damaged or destroyed. In Aleppo: the Al-Sultaniyeh mosque and the madrasa Al-Halawiyah. The Imam-al-Daur in Samarra. In Mosul: the masjid of al-Imam Ibrahim, the mausoleum of Imam Bahir, that of al-Immam Muhsin, the shrine of al-Imam Yahya ibn al-Qasim, and that of al-Imam ‛Awn al-Din (known as Ibn al-Hasan).

Aleppo: the Al-Sultaniyeh Mosque

Aleppo. Madrasa al Zahariyeh

Also known as the Al-Sultaniyah Madrasa, this 12th century building incorporates several rooms around the courtyard known as the Madrasaa al Zahariyeh. It was destroyed on December 7th 2014.[4]

Aleppo: the Madrasa Al-Halawiya

This Byzantine cathedral became a madrasa (Koranic school) in the 13th century. Attempts were made in 2013 to protect one of the wooden niches dating from this time. However this work had to be abandoned due to the conflict in the area.[5] The building was damaged recently in the same incident that destroyed the great mosque, with which it shared grounds.[6]

Samarra: the Mausoleum of Imam al-Daur

Samarra: the mausoleum of Imam al-Daur

Dating from 1085, this Shia shrine was destroyed in October 2014.[7]

Mosul: Masjid of al-Imam Ibrahim

Mosul. Masjid of al-Imam Ibrahim.

This building now appears to be destroyed in satellite photography.[8]

Mosul: the Mosque and Shrine of al-Imam al-Bahir

Mosul. Mosque of Imam Bahir.

This shrine was likely destroyed in September 2014.[9]

Mosul. Mausoleum of al-Imam al-Bahir

Mosul: the Mosque and Tomb of al-Imam Muhsin

Mosul. Mosque and tomb of al-Imam Muhsin (al-Madrasa al-Nuriya)

Also known as the madrasa al-Nuriya, this 11th century site was likely destroyed between December 2014 and December 2015.[10]

Mosul: the Shrine of al-Imam Yahya ibn al-Qasim

Mosul. Mausoleum of al-Imam Yahya ibn al-Qasim

This 13th century Shia shrine located on the Tigris riverbank and was destroyed as of July 2014.[11]

Mosul: Shrine of al-Imam ‛Awn al-Din (known as Ibn al-Hasan)

Mosul. Mausoleum of Imam ‘Awn al-Din.

One of the few structures to survive the Mongol invasion of Iraq, this 13th century shrine was reportedly destroyed on the 25th of July 2014.[12]

While it is impossible to undo the damage wreaked in some of the most archaeologically rich parts of this world, and there is frustratingly little that can be done to reverse the far greater loss of human lives, it is perhaps a small comfort to know that in some way we may contribute to the future preservation and potential reconstruction (digital or otherwise) of important monuments that are now lost.

Bibliography and further information

‘Ᾱdil N. ‘Abbū (1973) The Ayyubid domed buildings of Syria, PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh.

Ṭāriq Jawād Al-Janābī (1975) Studies in Mediaeval Iraqi Architecture, PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh.

UNESCO on the ancient city of Aleppo: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/21

UNESCO on Iraq: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/21 and http://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1239/

Monuments of Mosul in danger: http://monumentsofmosul.com/

Blue Shield Press on monuments in Syria and Iraq: http://www.ancbs.org/cms/en/press-room

A recent conference was held at the University of Edinburgh on Syria (between the departments of History, Classics and Archaeology, Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies and the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies).

References

[1] Some recent examples of this work: http://futurism.com/3d-imaging-is-helping-us-save-history-for-the-future/ and http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/next/ancient/digital-preservation-syria/

[2] see Abbu (1993), p. ii.

[3] Al-Janabi, (1975) chapter VI; and Abbu (1973) sections 4, 5 and 8.

[4] http://hyperallergic.com/168740/syrian-military-bombs-significant-13th-century-complex/ and http://www.syriaphotoguide.com/home/aleppo-al-sultaniyeh-mosque-%D8%AD%D9%84%D8%A8-%D8%AC%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%B7%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A9/ and http://apsa2011.com/apsanew/aleppo-partial-destruction-of-the-al-sultaniah-mosque-following-an-explosion-07-12-2014/#jp-carousel-4714

[5] http://apsa2011.com/apsanew/4074/

[6] http://www.syriaphotoguide.com/home/aleppo-great-mosque-%D8%AD%D9%84%D8%A8-%D8%AC%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%B1/ and http://eamena.arch.ox.ac.uk/impact-risks/explosives/

[7] https://www.cemml.colostate.edu/cultural/09476/iraq05-057.html

[8] http://monumentsofmosul.com/list2/18-i16

[9] Current satellite image: http://monumentsofmosul.com/list2/26-i35

[10] Current satellite image http://monumentsofmosul.com/list2/27-i37 and https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=017b3a45d45f439bb5e595491b9dc826

[11] http://monumentsofmosul.com/list2/8-i4 and http://archnet.org/sites/4356 and http://www.iraqinews.com/features/urgent-isil-destroys-1400-year-old-mosque-located-west-mosul/

[12] http://monumentsofmosul.com/list2/9-i5 and https://conflictantiquities.wordpress.com/2014/07/28/syria-iraq-islamic-state-destruction-shrine-mashhad-al-imam-awn-al-din/ and http://archnet.org/sites/3841