A large proportion of the earliest thesis we have digitised from the turn of the century are medical thesis. However, they little resemble the modern medical thesis being produced today. They are full of the personality of the students who wrote them and the people they studied. Sometimes it feels like we are hearing voices that no one has listened to for a very long time.

For example, one student named Donald Sutherland Murray undertook a study of an outbreak of alopecia he witnessed in the small town of 9000 people where he was practicing medicine. His study presents a cross section of the town, his patients ranged in age from 8 to 65, and were students, joiners, bakers, apprentice engineers and domestic servants. His thesis also includes beautiful portraits, such as the one below of a joiner, ages 35 with a ‘scanty moustache’. This thesis may no longer be relevant for the treatment of alopecia, but it provides information about people’s lives that would not have survived had they not suffered from alopecia.

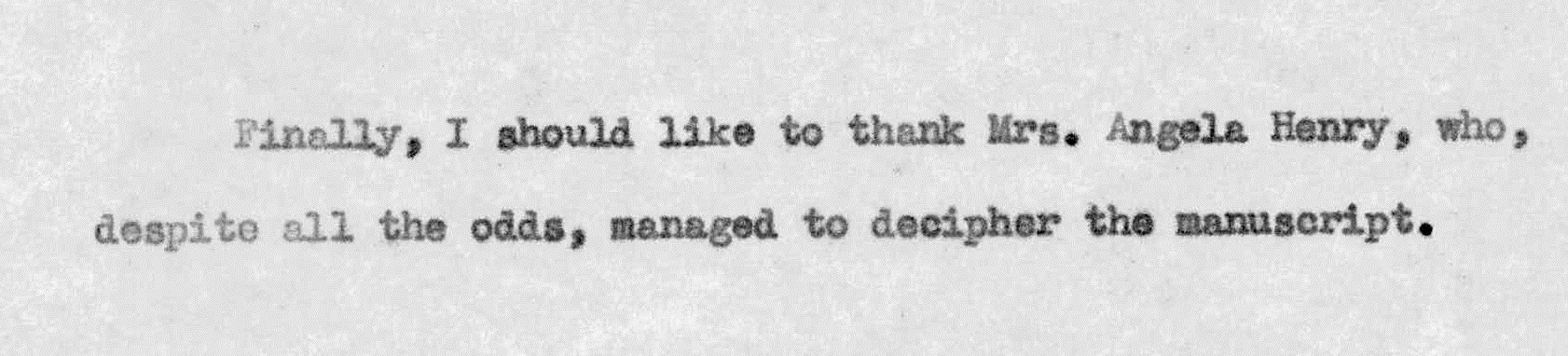

It is also important to remember that the people who produced the hundreds of volumes that pass through our hands and scanners every week were human beings who probably wept and had many sleepless nights in behalf of the work we are digitising. Sometimes it is rewarding to try to find out more about these individuals. A few months ago I came across a medical thesis from 1906 written by a woman called Sheila M. Ross. It is entitled Acute hallucinatory insanity – a type of the confusional insanities, with clinical notes. As female authors from this period are relatively unusual, I sought to find out a little more about Dr. Ross. I haven’t manages to find masses of information, but I did discover that she was awarded a medal from the School of Medicine in 1899 for Systemic Anatomy. The medal, along with a few others from the same time period, were sold for £170 by the auction house Dix Noonan Web. I have also found a record of her graduation in the July 1904 edition of the British Medical Journal. Of a graduating class of about 130, 7 were women, Sheila M. Ross, Aimee E. Mills, Margaret H. Robinson, Isabelle Logie, Amy M Mackintosh, Eslpeth M. McMillan, Margaret CW Young and Mildred ML Cather.

It is also important to remember that the people who produced the hundreds of volumes that pass through our hands and scanners every week were human beings who probably wept and had many sleepless nights in behalf of the work we are digitising. Sometimes it is rewarding to try to find out more about these individuals. A few months ago I came across a medical thesis from 1906 written by a woman called Sheila M. Ross. It is entitled Acute hallucinatory insanity – a type of the confusional insanities, with clinical notes. As female authors from this period are relatively unusual, I sought to find out a little more about Dr. Ross. I haven’t manages to find masses of information, but I did discover that she was awarded a medal from the School of Medicine in 1899 for Systemic Anatomy. The medal, along with a few others from the same time period, were sold for £170 by the auction house Dix Noonan Web. I have also found a record of her graduation in the July 1904 edition of the British Medical Journal. Of a graduating class of about 130, 7 were women, Sheila M. Ross, Aimee E. Mills, Margaret H. Robinson, Isabelle Logie, Amy M Mackintosh, Eslpeth M. McMillan, Margaret CW Young and Mildred ML Cather.

Much of the early thesis collection are MD’s, however, their value lies not just within the realm of medicine. Murray’s thesis contains a snapshot of life in a small town at the turn of the century, and is unique in that it is the only thesis on alopecia we have come across thus far. Ross’s thesis contains information about the prevalence of mental illness in Scotland and elsewhere, but it can also be used to learn more about the history of women’s participation in the University, and the School of Medicine in particular.

D.S. Murray’s thesis is being processed in the current block and should be available on Edinburgh Research Archive in the next few weeks. Once it has been uploaded a link will be added to this post.

![_DSC0008[1]](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/phddigitisation/files/2016/09/DSC00081-300x199.jpg)

![_DSC0013[1]](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/phddigitisation/files/2016/09/DSC00131-300x199.jpg)

![_DSC0017[1]](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/phddigitisation/files/2016/09/DSC00171-300x199.jpg)