Explore Scotland’s capital through the mind of one of Scotland’s greatest social thinkers and join us as we take a closer look at Professor Sir Patrick Geddes’ (1854-1932) photographic survey of Edinburgh.

From Pompei to the present day, humankind has sought to effect its civic surroundings. From promoting security and avoiding danger to eradicating disease and poverty and the promotion of health and well-being, the motives may change over time but often co-exist and are deeply interconnected, and they reflect the civic values of each society’s citizenry.

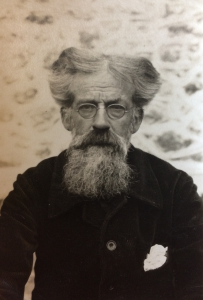

Patrick Geddes, aged 73, at Montpellier, c.1927 (Coll-1167)

Professor Sir Patrick Geddes (1854-1932) held a deep understanding of the complexities and inter-connectedness of civic change. Geddes made a unique and pioneering contribution to the fields of sociology and urban planning, not least through his tireless contributions, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, to regenerate the impoverished and dilapidated Old Town of Edinburgh.

Born in the Highlands of Scotland in 1854, Patrick Geddes studied biology and evolutionary theory in London, France and Mexico, before returning to Scotland in 1880 to teach biology at the University of Edinburgh. By the mid-1880s his interests had diverged to sociology, geography, ecology, education theory, cultural activism and urban planning. Geddes was a polymath and inter-disciplinarian.

Research conducted throughout his lifetime in Scotland, Europe, India, Palestine, the United States of America, and Mexico informed his conviction that the development of human communities was primarily biological in nature, consisting of interactions among people, their environment and their activities. Patrick Geddes died in Montpellier, France, in 1932.

Patrick Geddes and a group of children in front of the Outlook Tower (Patrick Geddes Collection, Ref: Coll-1167/B/23/12)

Geddes believed that civic regeneration ought to be informed by a comprehensive sociological understanding of the city, its region and their inter-relationships. He argued that geology, geography, climate, economic life, and social institutions should all be considered. The basic analysis for his civic survey was derived from his Frederick Le Play inspired triad ‘place, work and folk’.

The survey of Edinburgh and its region was the fundamental purpose of Geddes’ Outlook Tower. Geddes forged and disseminated many of his ideas in this six-storey social laboratory, situated on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, which he purchased and refurbished in 1892. Designed as a civic observatory, Geddes created a series of vertical exhibition spaces intended to help people understand the city in its wider context. He believed that the reconstruction of society would result from the co-operative efforts of informed individuals.

“The survey of our city and its region is of fundamental importance alike in the understanding of its past and present, and towards the preparation of the Greater Edinburgh of the near future.”

Patrick Geddes, 1919

Geddes amassed a vast collection of maps, views, plans, architectural drawings, photographs and other visual images at his Outlook Tower. The rooftop promontory offered the visitor a 360-degree view of the city of Edinburgh and its region. Together, these vivid and graphic representations illustrated the development of the city of Edinburgh over time, connecting its past to its present, and illuminating its relationship with the wider world. Geddes first exhibited a selection of visual material from his Outlook Tower collections at the Royal Institute of British Architects ‘Cities and Town Planning Exhibition’ in London in 1910. Exhibitions, were his favoured tool of civic education, where he set out and encouraged the adoption of his survey method.

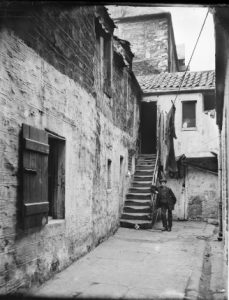

Tron Square, Edinburgh, (Patrick Geddes Collection, Ref: Coll-1167/B/27/4/5)

Photographs recording the built environment of Edinburgh and the way in which people lived and worked in it, were integral to Geddes’ Survey of Edinburgh. This type of photography was representative of a Scottish Visual Culture which was heavily influenced by Scottish Enlightenment philosophy. Great value was placed on empiricism and practicality, centred around values of improvement, virtue, and practical benefit for the individual and society as a whole. Geddes’ photographic survey forms part of a larger body of work of a network of late nineteenth century Scottish documentary photographers including Thomas Annan in Glasgow, William Donaldson Clark in Edinburgh, and John Thomson in London. Collectively, these photographs bore witness to the lives of the urban poor and were often used to inform social improvement programmes.

Brown’s Close, Canongate, Edinburgh, (Patrick Geddes Collection, Ref: Coll-1167/B/27/5/22)

The Photographic Society of Edinburgh established an Edinburgh Photographic Survey group in 1899, with the objective of creating a photographic record of Edinburgh. The Society subsequently staged an exhibition in 1904 which included 359 photographs. It is not clear whether the photographs used by Geddes in his Survey of Edinburgh were loaned to him from the Photographic Society of Edinburgh or in fact commissioned by him. It is thought that many may have been taken by photographers Francis Caird Inglis (fl.1880-1940) and Robert Dykes (fl. 1905-1906) and then a selection made and arranged for the survey by Geddes himself, assisted by Dykes, and two of his children, Norah Geddes (1887-1967) and Alastair Geddes (1891-1917), along with his God-daughter, Mabel Barker (1885-1961).

In the 1880s, Edinburgh’s historic Old Town was afflicted by degraded buildings and social deprivation. Whilst apt to meet the needs of the well-to-do, historically, planners had neglected the needs of all citizens. In failing to provide space for work-shops and industry, Geddes argued that this lack of foresight inevitably led to the unchecked filling up of any and every vacant space with any and every sort of irregular and utilitarian factory and workshop. Thus stately residential order and plan-less squalor could be found on opposite sides of the same street.

Geddes’ Survey of Edinburgh was a call for civic engagement and co-operation. Geddes asked:

“what can be done here and there meanwhile with moderate means and ordinary folk, with such labour and time as they can spare?” Patrick Geddes, 1915

Children’s Garden, Johnston Terrace, Edinburgh (Patrick Geddes Collection, Ref: Coll-1167/B/27/10/9)

The Outlook Tower Open Spaces Committee surveyed every open space amid the slums of Edinburgh’s Old Town. They measured 75 pieces, totalling 10 acres. By 1911, over 10 of these had been reclaimed and turned into gardens and were accessible to local-residents, particularly women and children.

By encouraging local people to directly participate in the beautification, art, culture and education of their local community, Geddes provided citizens with the means to influence their local environment. He inspired regeneration from within the community.

Geddes believed that access to nature and natural conditions were essential to mental and physical health, and brought public beauty to areas of former squalor. He understood that private gardens, city parks and the surrounding countryside were often not within the reach of Edinburgh’s Old Town working class and poor. He recommended garden quadrangles replace wasted courts and drying greens so that family members, young and old, could employ themselves together in happy garden activities. This configuration of small proximal green spaces to Old Town residents would be far more accessible and useful to the daily use of childhood and family life.

“What better training in citizenship, as well as opportunity of health, can be offered any of us than in sharing in the upkeep of our parks and gardens?” Patrick Geddes, 1915

Many of the green spaces still to be found in Edinburgh’s Old Town today are due to the work of Geddes over a century ago. In 2020, Johnston Terrace Garden is the smallest of 123 wildlife reserves managed by the Scottish Wildlife Trust and is teaming with frogs, bees, butterfiles and birds.

Over 250 of the original, glass-plate negatives from Geddes’ Survey of Edinburgh survive within the Patrick Geddes Collections at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections. In September 2020, the University collaborated with Google Arts & Culture to make their collections more accessible to a wider audience. Among the collections featured are a series of photographs from the archives of Sir Patrick Geddes. View ‘Surveying Edinburgh: Civic Regeneration Under Patrick Geddes’ via Google Arts and Culture. Browse through a further 70 images from the collection online via the University of Edinburgh’s Image Collections website. It is also possible to view the original glass plate negatives and prints made from the negatives in person at the Centre for Research Collections. Please visit the Centre for Research Collections web-pages for up to date information and guidance on how you can access collections.