“When we finally arrived at the boundary wall of the early 19th century cottage, now known as ‘Gean Cottage’, I found myself quite moved. Here I was, where Geddes had been…albeit there was almost 100 years between our existence”. Recently, our project archivist, Elaine MacGillivray, took some time out from her cataloguing work to reflect on Patrick Geddes in his native Perthshire environment.

Patrick Geddes and his daughter Norah in the garden at Mount Tabor, Perth, c.1899 (Coll-1167/GFP)

Archivists bear a weight of responsibility in our privileged position as custodians of society’s memory; what we do will matter hundreds of years from now. We aim to effectively manage collections by creating well-informed, reliable and detailed information about the content of the collections to ensure their long-term survival and access to the collections’ content. To do this requires a deep understanding of the collection and its creator.

Archivists, as a breed, are renowned for immersing ourselves in the detail of our work and, whilst the detail is important, we are often guilty of forgetting to lift our heads to look to the big picture. Working so closely with the Geddes collections is a constant reminder to lift your head and look out. The collections abound with illustrations of panoramic views of regions, cities and landscapes. There are thousands of illustrations and diagrams which demonstrate the interrelationships and connections between and beyond the boundaries of specialisms. Prolific correspondence and writings reveal Geddes’s beliefs, one of which was that, to better understand a place, one should view it from a position of outlook.

Patrick Geddes and family at Mount Tabor, Perth, c.1899 (Coll-1167)

In 1857, the Geddes family moved from Ballater, Aberdeenshire, to ‘Mount Tabor’, a cottage on the side of Kinnoull Hill overlooking Perth. Patrick Geddes was three years old at the time and he remained there until he was twenty when he left to continue his studies. I recently had the opportunity to take to the Perthshire hills in his footsteps, to see the world through something of his eyes and experience. This was also a chance to remove myself from the detail of collections cataloguing and to lift my head and look out. I could immerse myself in quiet reflection in the natural environment and by doing so to deepen my understanding of Patrick Geddes. I think he would have approved.

One rather fresh but clear weekend in early April a colleague and I set out from the Den of Scone on our Perthshire/ Geddes pilgrimage. We began surrounded by mature trees and despite being spring there were not yet buds on the trees and the remnants of autumn detritus still covered the woodland floor. We followed a muddy track (insert squelching noises) and to our right ran a burn. We crossed the burn by a footbridge and then the path climbed more steeply eastward. Occasionally we crossed a single track road banked by a high beech hedge on one side and spiked holly bushes on the other. At Bonhard House we turned southwards and navigated the path alongside the ploughed fields which flank the eastern edge of the valley, stopping periodically to watch and listen to a buzzard being harassed by crows.

We ascended the steep Coronation Path and at the top took a rest and absorbed what we could of the impressive panoramic vista, looking west towards Ben Lomond and north-west toward Ben Lawers, Schiehallion and finally the snow-capped Grampian mountains in the far north. Having checked historical maps before embarking on our journey I mentally picked off the farms and place-names which would have been extant c.1860 and which Geddes would also have seen: Springfield; Parkfield; Limepotts; Muirhall; Corsiehill; Gannochy, and Kinnoull Hill. My colleague and I chatted about the probability of Geddes walking and exploring these very routes 150 years before us, all the time learning and forming the beginnings of ideas which hold such significance and relevance to us today.

We came by way of the back-streets of Corsiehill and here I tried to visually erase all of the new housing which post-dates Geddes’s time at ‘Mount Tabor’. When we finally arrived at the boundary wall of the early 19th-century cottage, now known as Gean Cottage, I found myself quite moved. Here I was, where Geddes had been. This man that I had been working so closely with for the best part of a year, albeit that there was almost 100 years between our existence.

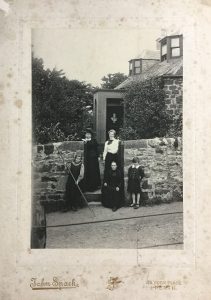

Anna Geddes, Miss Scott, Janet Cuthbertson, Norah and Alasdair Geddes at the garden gate of Mount Tabor cottage, Perth, c.1899 (Ref: Coll-1167/GFP)

Among the many wonderful family photographs there is an image by Perth photographer, John Spark, of Geddes’s wife, Anna and their children at the garden gate. The ivy has grown up and over the garden wall now and the garden itself is much more manicured. I found myself placing my hand on the garden wall beside the gate, wondering how many of the Geddes family had touched the same spot. And while I have never taken for granted the immediate and emotional connection to our past that archive collections can afford us, I was struck afresh by this new and very tangible connection to Patrick Geddes.

Project Archivist, Elaine MacGillivray, at the garden gate of childhood home of Patrick Geddes, the former Mount Tabor cottage, Perth, 2018.

I was able to experience first-hand much of the environment that informed Geddes’s understanding of place, ecology, botany and so much more and which was undoubtedly instrumental in the formulation of his geographical vision, the Valley Section. I reflected on how Geddes was able to perceive the inter-connectedness and inter-relationships of just about everything, fueled by his place of outlook from Kinnoull Hill. That interconnectedness and those interrelationships are so key to his ideas and beliefs that as archivists, we have a duty to find a way to reflect them through our archive finding aids and collections catalogues. But that’s a whole other blog post. The next time I lift my head and look out, I might write that.

Read more about Patrick Geddes and Perth in this blog post from Professor Murdo MacDonald

Find out more about Kinnoull Hill and Perthshire in the time of Geddes by viewing historical maps online via the National Library of Scotland and a little earlier in the 1845 Statistical Account for the Parish of Perth