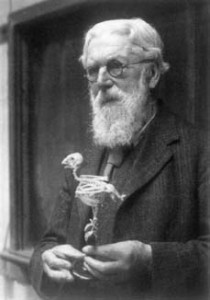

Disgruntlement. The archives are full of it – though I should stress I am referring to the contents of our records rather than our lovely readers (or indeed my lovely colleagues)! This week’s letter is a wonderful example of disgruntlement from the eccentric and brilliant zoologist and classicist, D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson (1860–1948). The youth, he tells us, simply aren’t what they used to be:

Thompson wrote the letter to Thomson in 1946 to congratulate him on his Galton Lecture, ‘the Trends of National Intelligence’, which explored the idea that as a nation, our intelligence was in decline.

Thompson wrote the letter to Thomson in 1946 to congratulate him on his Galton Lecture, ‘the Trends of National Intelligence’, which explored the idea that as a nation, our intelligence was in decline.

While he acknowledges that he may well be ‘biased by the disgruntlements of old age’, he assures Thomson:

I still believe that my students are inferior to those of thirty or forty years ago, and to my own companions of 60-70 years ago. They have less ability, much less diligence, and hardly any of the old enthusiasm and joy and happiness in their work.

And that, according to Thompson, isn’t even the half of it!:

There is something, something very subtle and mysterious, which brings the Golden Ages and the Dark Ages; which gives one, in literature, the Elizabethan, the Queen Anne, and the Victorian periods; and in Art the great and shortlived glories of Greece, Italy, Holland and our English school of Reynolds, Turner, Constable and the rest. All gone!

Indeed. And according to Thompson, who finishes on a wonderful note of pessimism, its only going to get worse:

I judge from the young people I have to do with, that we are going to be worse before we are better.

But despite appearances, Thompson loved teaching – he was a renowned speaker whose lecture halls were packed, and he encouraged his students to exercise their enquiring minds. Even while he lay on his death bed, Thompson’s students visited and livened up his last days with discussion and debate. Any disappointment hinted at in his letter to Thomson could be attributed to his own brilliance, which perhaps caused him to expect similar levels of extraordinariness in those he taught.

Thompson’s love of biology was awakened by his Grandfather, who, along with Thompson’s Aunt, brought him up in Edinburgh. This was due to the death of his Mother and his Father’s appointment as professor of Greek in Queen’s College, Galway. He was educated at the Universities of Edinburgh and Cambridge – gaining a first, naturally, and was appointed professor of biology in University College Dundee.

The importance of artefacts in teaching was clear to Thompson from the outset. Under his guidance a rich museum of zoology was created, helped by the Dundee whalers. Thompson himself was deeply interested in whaling, visiting the Pribylov Islands as a member for the British–American ‘inquiry on the fur seal fishery in the Bering Sea’. This interest would continue throughout his life, seeing him speaking at international conferences; appointed CB (1898); becoming a member of the fishery board for Scotland; and becoming a British representative for the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. In 1917, Thompson accepted the post of senior chair of natural history in the United College of the University of St Andrews.

Thompson’s published output was vast, and included papers on biology, oceanography, classical scholarship, and natural history. He had several honours bestowed upon him, including his election as fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1885); his election as fellow of the Royal Society (1916); the Linnean gold medal (1938); the Darwin medal (1946); and his knighthood (1937). Despite his description of himself as a ‘disgruntled old man’, Thompson encouraged the youth surrounding him to think, to enquire, and to explore – something he did right up until the end of his life.