A recent post on this blog, Fairbairn’s Dream Drawings #1, explored the subject of William Ronald Dodds Fairbairn’s dream drawings, which date from the 1950s. The focus of that first post were Fairbairn’s drawings of landscapes. For this return to the subject, I will be focusing on the drawings in which Fairbairn brings to life a cast of interesting characters.

When looking through the drawings in the William Ronald Dodds Fairbairn Archive it becomes immediately apparent that many of the characters in Fairbairn’s dreams made regular appearances. The men, women and children are drawn wearing distinctive clothing or they perform distinctive activities. Some of the recurring characters include a middle-aged women, often in Edwardian looking dress, redolent of Mary Poppins, a child in traditional Scottish dress, often with a dog, and a seated male figure. It is likely that the child represents Fairbairn himself, and the man and woman are perhaps his parents, however, it is not my intention here to offer explanations or interpretations of these characters; I’m sure you will form your own opinions about that.

The female character is often depicted leading the child from a chain around his neck, or brandishing a weapon, typically a sword or stick:

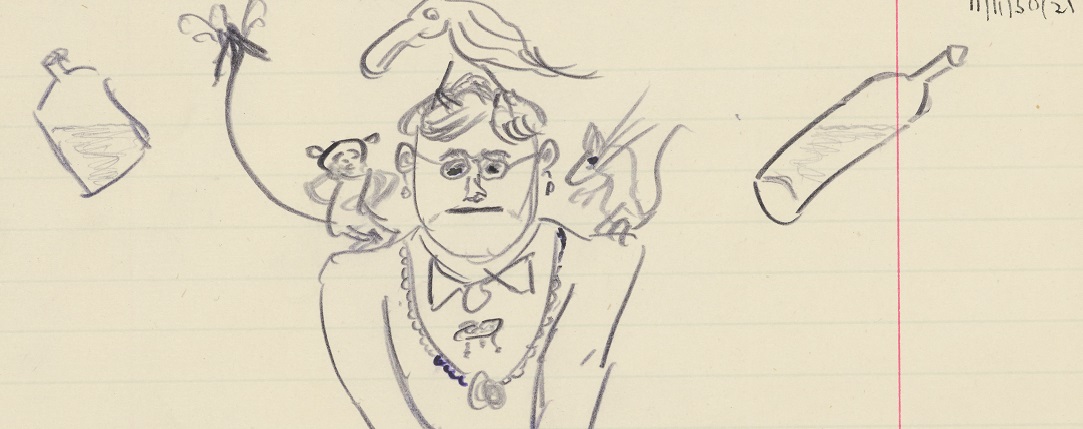

However, on occasion she is portrayed in a slightly less menacing way, such as below.

As with the first image on this post, the image below includes the majority of the pantheon of Fairbairn’s dream characters.

Whilst the majority of the characters in Fairbairn’s dream drawings are recognisable as humans, there are a few that have a more abstract feel. What do you think Fairbairn’s subconscious was trying to tell him here?