Alexander Murray Drennan – or Murray to his friends – was born in Glasgow on 4th January 1884, and grew up in Helensburgh before coming to Edinburgh in 1901 to study medicine. Murray was a keen letter writer, and his letters to his sweetheart ‘Nan’ (Marion Galbraith, who would later become his wife) give an insight into the life of a young aspiring medical student:

Our first class begins at 8am so we have to be up betimes in the morning. From 8 to 10 I have anatomy and then at 11 I go over to the Infirmary; nominally we leave there at 1pm but on Operation days, twice a week at least, it is often 3 before I get away as I have the pleasure of being the instrument clerk and as such have to see after the instruments.

– GD9/45

It wasn’t all hard work, though. Murray’s letters to Nan and his family recount evenings spent at enjoying Edinburgh’s cultural offerings (“I went to see Faust on Monday night. It is rather a ‘creepy’ sort of opera but the music is very fine”); attending dinners (“at night there was a complimentary dinner given to Professor Beattie in the Caledonian Hotel … Beattie was very popular when he was here and no wonder for he was an exceptionally nice man and knew his work thoroughly”) and afternoons spent playing tennis and golf with fellow students as well as professors (“Professor Schӓfer had the goodness to ask me down to North Berwick to golf with him … a most enjoyable day’s golf in the most delightful weather. We went back to the house and had tea and then I had just time to get the 6.43 train back”).

Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh Residents, Summer 1907. Drennan is seated front row, far right.

After graduating MB ChB in 1906, Murray took up a practical apprenticeship as a Resident of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. In between visiting patients and supervising the various nurses, clerks, dressers and medical students who attended the wards, the Residents made time to enjoy themselves (you can find out more about their antics over on the LHSA blog). In one letter to Nan, Murray related a night out for the ‘Mess’:

RIE Residents on a bus, ready for an outing.

Friday … evening at 9pm, the Mess having chartered a visitor bus (& driver) set out for Peebles. It created quite a sensation when at the appointed time one of these large buses labelled “Jeffery’s Lager” rolled up to the door & we all embarked. The inside was converted into smoking room, saloon bar, while the upper deck was occupied by the sightseers. It was very funny going out Dalkeith Rd, several people tried to get on board thinking it was a public conveyance, needless to say their attempts to mount our machine were not encouraged by word or deed. The run out was delightful as it was a clear warm evening & the road lies through pretty country. We got to Peebles shortly after 11pm & found supper all ready for us at the ‘Cross Keys’ inn. As usual the Mess meeting was constituted & we did full justice to the repast, reembarking again about 12.40am.”

– GD9/46

Following his residency Murray stayed close to home, working in the by-now familiar Pathology Department of the University of Edinburgh. When war broke out in 1914, he signed up as an official Pathologist with the Royal Army Medical Corps (R.A.M.C), and in 1915 he had to postpone an imminent appointment as the first full-time Professor of Pathology at the University of Otago in New Zealand and instead make his way to the R.A.M.C. Depot in Aldershot. In a letter home dated October 1915, he describes some of the men he will serving with and the set-up of their team:

The staff seem all very decent men, one or two are well over forty & must have been in practice. There are several Edinburgh graduates amongst them … on the whole I think we should work well together … There are two or three surgical specialists, one medical specialist, several radiologists, several anaesthetists and one bacteriologist … there is a little man Brown who has done a little in that way & I shall try & get him on to help, but he does not profess much technical knowledge!

– GD9/7

In early November 1915 Murray’s unit was deployed to Mudros, on the island of Greece. He would later describe how this previously “bare, stony island” was overtaken by military personnel:

As the occupation spread the whole of the harbour side of the island was dotted with tents from Mudros East to Condia on the west. It was a shifting population, today 10000, next week perhaps 60000. The only permanent fixtures, so to speak, being the various H.Q.s, the Base depots and the Hospitals.

To the north a little outside Mudros East were several stationary hospitals situated on a sun-baked flat, and there they bore the burden of the day; blinded with dust and flies and crowded up with cases of dysentery, the staff often sick, they cheerily toiled along. In the neighbourhood also were numerous camps of combatant units; and one bright spot, facetiously known as the “dogs’ home”, where extra medical officers were kept on the chain and supplied as required to the Peninsula or to units on the island.

– GD9/38

Murray’s letters home to Nan and their children from this time paint rather a relaxed picture of life in war time. Reading them, one is left with the impression that he only wanted to recount activities that his wife would be familiar with, rather than the full realities of a life in an overseas field hospital. One letter, for example, describes how they spend their evenings: “After dinner we had our usual games at whist. It is quite an institution and we have played every evening after dinner, always Richards and Thuilliers against the Colonel and me, and so far the games have been very even”. In another letter, Murray talks of attending a garden party: “it was just quiet tea in the Fergusons’ little garden, a shady spot with palms, & bougainvillea, & such things growing about. … We had tea & chatted & then left in small batches”.

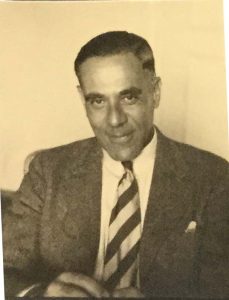

Alexander Murray Drennan in Cairo, 1915

By 1915 some of Murray correspondents had already been stationed abroad for some time, and his incoming letters give insights into some very different military experiences. Murray’s younger brother James Stewart Drennan (who had joined the Royal Horse and Field Artillery in 1912) described life in Salonika and a close encounter with a German zeppelin:

It has been beastly hot here again the last few days and we have now chucked working in the middle of the day, instead we lie on our beds in a more or less nude condition and curse the flies, luckily it is still nice and cool at night.

Salonica [sic] had another visit from a Zepp. three or four days ago, just before daylight. All the guns and searchlights in the place got on to it at once and it was brought down before it had a chance of dropping any bombs. It came down in the marshes at the mouth of the Vardar River and the men were captured, so were felt rather bucked at having bagged a Zepp in this corner of the world.

– GD9/10

A letter from Tom Graham Brown, physiologist and mountaineer, gives an insight into the life of medical personnel at home:

Write me a decent letter and tell me all your news. I wish I was out there with you. I am at present fixed in this hospital which is one for shock cases – mostly men who are pretty badly shaken or bad mentally after bombardments. Very many of them get well – tho’ we get a good many early G.P.I’s before they are diagnosed.

I wish all the same that I could get out. It isn’t any catch being in this country. However I must trust to luck.

– GD9/4

Yet another perspective was provided by Dr John Fraser (later Prof. Sir John Fraser, Principal of University of Edinburgh). Dr Fraser was stationed in Northern France, and his letters describe the long, difficult days the staff there endured:

Lately we have been deluged with work: you can probably imagine what Monday was like. I was in the theatre from 10am to 12 midnight, and in that time there were 6 craniotomies: an amputation and 2 gas gangrene: in addition to others. One doesn’t feel much inclined for reading or writing after such days.

– GD9/100

There were benefits to working in such tough conditions, however. War often brings about significant advances in technology and medicine: as well as the greater incentive to improve the health of fighting forces, the need to take risks and experiment can also increase.

Many of the battles of WW1 took place on muddy farmland, and it could sometimes be days before a soldier was transported to a clearing hospital for comprehensive treatment. This meant the risk of already-traumatic wounds becoming infected was high, with gangrene claiming many lives.

For some time prior to his deployment Murray had been working with colleagues in the Pathology Department at the University of Edinburgh “to find an antiseptic which could be applied as a first dressing in the field to prevent sepsis”[1], and in 1915 they published a paper in the British Medical Journal on their experiments with ‘Eusol’, or Edinburgh University Solution of Lime. This was a combination of bleaching powder and boric acid, and early experiments both in the wards and in the field showed great success at reducing infection and speeding up healing.

In gathering accounts of these experiments, Murray relied on other colleagues who were using the Eusol treatment. This letter from Dr Fraser sets out the dilemma faced by many front-line surgeons, and his experience using Eusol:

Since I last wrote you I have had a run of gas gangrene cases, all of them I have treated with Eusol and in each case I have been thoroughly satisfied with the result. With one case I was exceedingly impressed. Lt. Col. —- had been infected 5 days before admission to the Hospital – on admission there was most gangrene to the lower of the knee: from this knee to the groin there was the gas infection of the tissues which precedes the tissue necrosis. One was faced with three possibilities – 1. Leaving him alone to die 2. Doing a flapless amputation at the hip joint: a mutilating operation from which few recover 3. Amputation through the centre of the thigh, in other words, through the centre of the gas infected area, and risking it.

I chose the last: I did the operation under Special Anaesthesia and as I was doing the operation I remarked that it ought to satisfy the criteria as regards the use of Eusol. I amputated through the thigh and not only so but I made flaps and partly closed the wound, a thing one had never dared to attempt previously… The result was a complete success: no trace of gangrene appeared subsequently.

– GD9/100

A further hurdle to be overcome in wartime was the difficulty in communicating such advances. Recognising the delays to the mail that could occur, Murray devised a system for himself and Nan:

I sent off my last to you on Sunday afternoon, & I labelled it no.1 as I explained so that you would know by the number if a letter was missing, of course I have sent several to you before I began the numbering. This is a recapitulation in case you didn’t get my last letter.

– GD9/4

Murray also kept a small diary in which he recorded letters sent and received – an absolute dream for archivists and researchers!

There are roughly 6 archive boxes of letters like this – thankfully Drennan had a system by which to organise them!

No such system was in place for the medical men, however, and correspondence over a number of weeks between Murray, J. Lorrain Smith and Fraser details the somewhat arduous process of getting an article published.

I am sorry to have been so lazy in getting this note away, but during the last week the pace of work has increased and although [things are quieter] at present, if I do not get these away now it may be a long while before I have another opportunity.

– Fraser to Drennan, 17 Sep 1915

For the past fortnight I have been cut off from all correspondence and your letter and the manuscript were awaiting me here on my return. I have handed the manuscript to the Colonel and he has approved of it: he forwards it to the DMS [Director of Medical Services] and who if he approves will forward to the War Office: the WO will notify the BMJ or Dr Fletcher to proceed with the publication. The ways of the army are wonderful but there they are!

– Fraser to Drennan, 5 Dec 1915

By 1916 Eusol was an established means for treating septic wounds, and even today[1] hypochlorus acid forms a backbone to attempts to accelerate wound healing.

After being discharged from service in 1916, Murray was finally able to take up his place in New Zealand, with his wife and children joining him shortly after. They remained there until 1929 when Professor Drennan took up the Chair of Pathology at Queen’s University in Belfast, and in 1932 he returned to his alma mater to take up the Chair at the University of Edinburgh, where he remained until his retirement in 1954. Professor Drennan died in 1984, a few weeks after his 100th birthday.

Alexander Murray Drennan and family on a picnic in Dunedin, New Zealand.

References

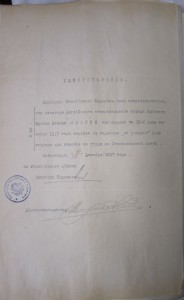

Ernst Levin (1887 – 1975)

Ernst Levin (1887 – 1975)