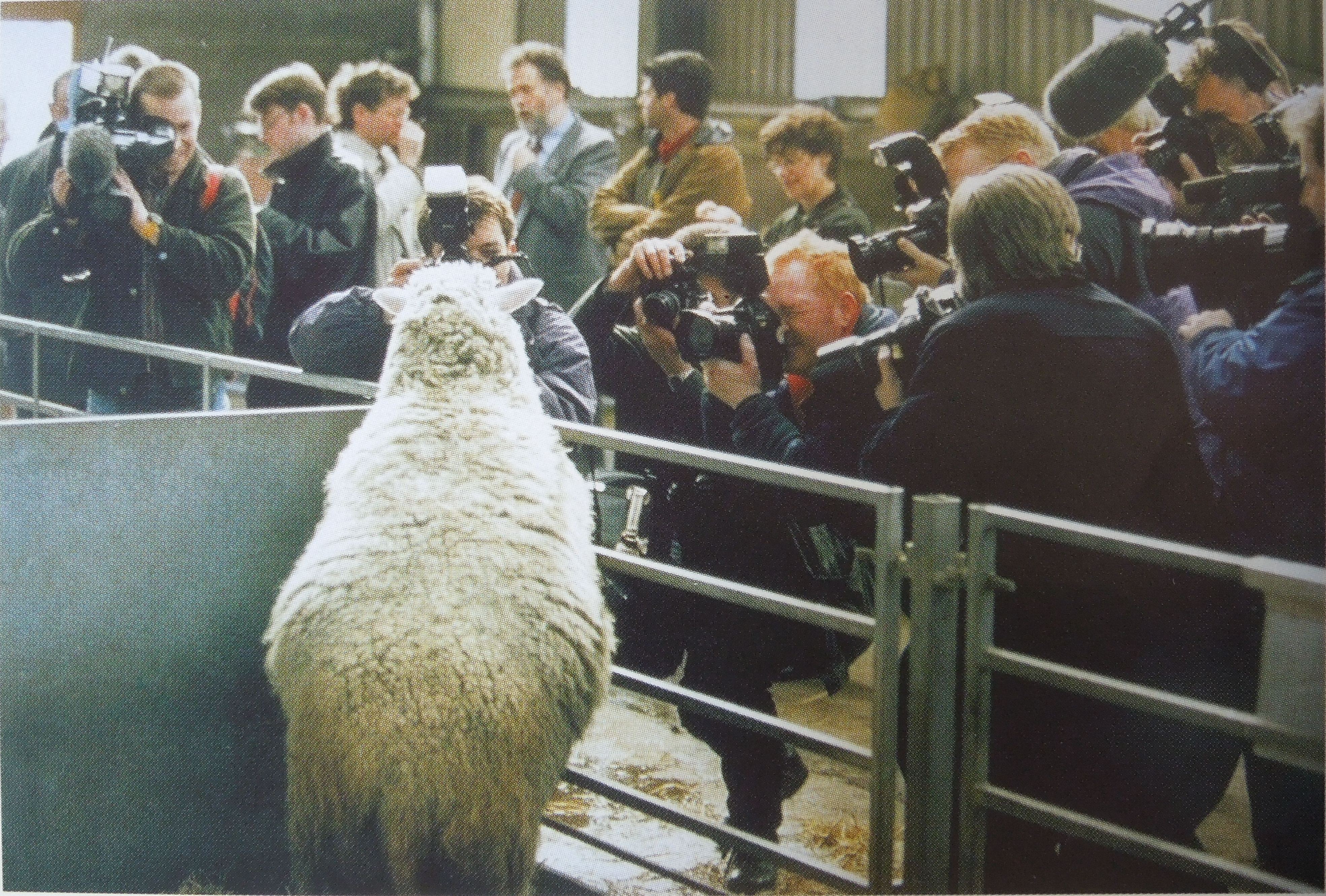

As mentioned in a previous post, Dolly, the sheep caused a media sensation in 1997 as the first cloned animal using a nuclear transfer process and so, I thought it would be interesting to highlight several articles that I came across on Dolly and cloning at the Roslin Institute in 1998 and then again in 2006. I wondered what cloning research had developed over the years since Dolly, the sheep’s birth in 1996 and surprisingly, or not, the articles I came across (that evoked Dolly) dealt with the issue of eating cloned animal meat and the ethical debate of cloning humans for medical purposes.

Note: these four articles are just a sampling of the articles produced by the Roslin geneticists on the issues, debates and research surrounding Dolly, nuclear transfer, animal and human genetics, cloning purposes (medical, agricultural, genetic conservation, etc..) to illustrate what way being discussed at the time. For more articles on these subject, please consult the Roslin Institute off-prints for 1998 and 2006 at GB237 Coll-1362/4/.

In the 1998 Roslin off-print bound volumes, I found Harry Griffiths report, ‘Update on Dolly and nuclear transfer’ in the Roslin Institute, Edinburgh: Annual Report April 1, 97-March 31 (GB 237 Coll-1362/4/1848) and Sir Ian Wilmut’s article, ‘Cloning for Medicine’ in Scientific American, December 1998 (GB 237 Coll-1362/4/1897). Griffiths report describes Dolly’s creation by the Roslin geneticists and notes that their breakthrough caused several other groups to ‘take advantage of public interest in cloning to advertise their successes …. Calves cloned from adult animals were reported from Japan and from New Zealand.’ The New Zealand clone was from ‘the last surviving animal of a rare breed’ which highlighted the use of cloning to preserve endangered species. He continues with discussing Intellectual Property issues in relation to Professor Yanagimachi and his colleagues at the University of Hawai’i ‘Honolulu Cloning Technique’ and closes with a couple of paragraphs on human cloning. He notes the UK Human Genetics Advisory Commission and the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority’s report ‘Cloning issues in Reproduction, Science and Medicine’ from 7 December, 1998 which recommends that ‘there should be a continued ban on all ‘reproductive cloning’ – the cloning of babies – but gives cautious support to the cloning of human cells for therapeutic purposes.’

In the 1998 Roslin off-print bound volumes, I found Harry Griffiths report, ‘Update on Dolly and nuclear transfer’ in the Roslin Institute, Edinburgh: Annual Report April 1, 97-March 31 (GB 237 Coll-1362/4/1848) and Sir Ian Wilmut’s article, ‘Cloning for Medicine’ in Scientific American, December 1998 (GB 237 Coll-1362/4/1897). Griffiths report describes Dolly’s creation by the Roslin geneticists and notes that their breakthrough caused several other groups to ‘take advantage of public interest in cloning to advertise their successes …. Calves cloned from adult animals were reported from Japan and from New Zealand.’ The New Zealand clone was from ‘the last surviving animal of a rare breed’ which highlighted the use of cloning to preserve endangered species. He continues with discussing Intellectual Property issues in relation to Professor Yanagimachi and his colleagues at the University of Hawai’i ‘Honolulu Cloning Technique’ and closes with a couple of paragraphs on human cloning. He notes the UK Human Genetics Advisory Commission and the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority’s report ‘Cloning issues in Reproduction, Science and Medicine’ from 7 December, 1998 which recommends that ‘there should be a continued ban on all ‘reproductive cloning’ – the cloning of babies – but gives cautious support to the cloning of human cells for therapeutic purposes.’

Wilmut’s article in Scientific American reports on the how biomedical researchers are developing ways to use genetically modified mammals for medical purposes. He mentions the sheep, Megan and Morag who were the first mammals cloned from cultured cells. A technique that allows cloned sheep to carry human genes and such animals produce milk that can be processed to create therapeutic human proteins. The sheep, Polly, is a transgenic clone of a Dorset sheep and ‘a gene for a human protein, factor IX, was added to the cell that provided the lamb’s genetic heritage, so Poly has the human gene.

Wilmut’s article in Scientific American reports on the how biomedical researchers are developing ways to use genetically modified mammals for medical purposes. He mentions the sheep, Megan and Morag who were the first mammals cloned from cultured cells. A technique that allows cloned sheep to carry human genes and such animals produce milk that can be processed to create therapeutic human proteins. The sheep, Polly, is a transgenic clone of a Dorset sheep and ‘a gene for a human protein, factor IX, was added to the cell that provided the lamb’s genetic heritage, so Poly has the human gene.

In the 2006 Roslin off-print bound volumes, I found two fascinating articles:– Sir Ian Wilmut’s ‘Human cells from cloned embryos in research and therapy’ in BMJ Vol. 328, February 2004 and J. Sark, et al.’s ‘Dolly for dinner? Assessing commercial and regulatory trends in cloned livestock’ in Nature Biotechnology, Vol. 25, No. 1, January 2007.

Sir Ian Wilmut’s article ‘Human cells from cloned embryos in research and therapy’ in BMJ Vol. 328, February 2004 is one of the more contemporary papers in the collection that discusses stem cell technology and human cloning issues. He cites studies of human genetic diseases and how cloned cells ‘will create new opportunities to study genetic disease in which the gene(s) involved has not been identified’, specifically describing work with motor-neurone diseases. Then, Wilmut notes how stem cells could be used in treatments for a variety of degenerative diseases, i.e. cardiovascular disease, spinal cord injury, Parkinson’s disease and Type I diabetes. Finally Wilmut discusses the differences in regulation of nuclear transfer and human cloning in various countries, noting that in the United Kingdom, ‘project to derive cells from cloned embryos may be approved by the regulatory authority for the study of serious diseases. By contrast human reproductive cloning would be illegal.’

Sir Ian Wilmut’s article ‘Human cells from cloned embryos in research and therapy’ in BMJ Vol. 328, February 2004 is one of the more contemporary papers in the collection that discusses stem cell technology and human cloning issues. He cites studies of human genetic diseases and how cloned cells ‘will create new opportunities to study genetic disease in which the gene(s) involved has not been identified’, specifically describing work with motor-neurone diseases. Then, Wilmut notes how stem cells could be used in treatments for a variety of degenerative diseases, i.e. cardiovascular disease, spinal cord injury, Parkinson’s disease and Type I diabetes. Finally Wilmut discusses the differences in regulation of nuclear transfer and human cloning in various countries, noting that in the United Kingdom, ‘project to derive cells from cloned embryos may be approved by the regulatory authority for the study of serious diseases. By contrast human reproductive cloning would be illegal.’

Then, in 2007, the article by and J. Sark, et al’s ‘Dolly for dinner? Assessing commercial and regulatory trends in cloned livestock’ in Nature Biotechnology, ‘reviews the state of the art in cloning technologies; emerging food-related commercial products; the current state of regulatory and trading frameworks, particularly in the EU and the United states and the potential for public controversy.’

Then, in 2007, the article by and J. Sark, et al’s ‘Dolly for dinner? Assessing commercial and regulatory trends in cloned livestock’ in Nature Biotechnology, ‘reviews the state of the art in cloning technologies; emerging food-related commercial products; the current state of regulatory and trading frameworks, particularly in the EU and the United states and the potential for public controversy.’

As you can see by these four examples there are a range of issues and concerns that have been discussed over the years. While advances are made in cloning and genetic modification, there are still ethical debates to be had and more research to be done. In reading over these and other similar articles in the Roslin off-prints, I enjoyed learning about the different uses of transgenic animals.