Giving lectures is a prominent aspect of working life for many academics, as the animal genetics archives here at Edinburgh University Library Special Collections show. Most of the collections of scientists’ personal papers contain information relating to academic and public lectures given, and frequently also include copies of the lectures themselves, some dating back as far as the 1940s. This material gives a fascinating insight into how genetics teaching has changed and evolved over the decades, but we don’t always hear about the experience of lecturing from the point of view of the listening students. Anecdotes occasionally survive about teachers who were particularly memorable (for both good and bad reasons!). James Cossar Ewart, Professor of Natural History at the University from 1882-1927, was instrumental in establishing genetics as an academic subject at the University of Edinburgh in the early twentieth century, but his reputation as a lecturer is not quite as gilded. One of his students, Maurice Yonge, remembered that Ewart’s lectures were ‘conducted amid scenes of riot and general pandemonium, Ewart…being unable to control the class. Indeed, at times…so chaotic were the proceedings, that only the movement of Ewart’s large walrus moustache indicated he was still lecturing.’ On the other hand, the first director of the Institute of Animal Genetics, F.A.E. Crew, was a charismatic and inspiring teacher, as his friend and colleague Lancelot Hogben recalled: Continue reading

Author Archives: towardsdolly

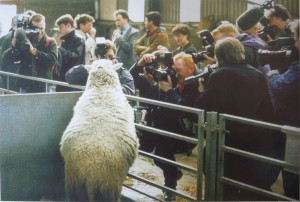

Science: Media Friendly?

Nowadays we are more than accustomed to scientists appearing on television and radio to talk about their research or engage in debates about the social, political and ethical implications of science. The archives of the Roslin Institute and the personal papers of Ian Wilmut testify to the increasingly public-facing role of scientists, which a glance at the file upon file of press enquiries about Dolly the sheep reveals. In the book The Second Creation, Ian Wilmut states that ‘nothing could have prepared us for the (literally) thousands of telephone calls, the scores of interviews, the offers of tours and contracts and in some cases the opprobrium’ which would follow the announcement of Dolly’s birth. The relationship between science and the media can be a prickly one – Dolly’s birth led to hysterical press reactions about potential human cloning – but it also allows for open public debate about the wider implications of scientific research which can affect us all.

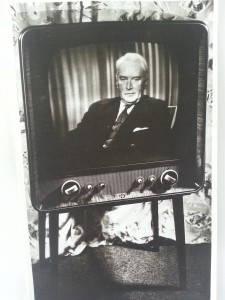

Historically, we can trace the continuing increase in scientists’ public presence in tandem with the growth of the media industry throughout the twentieth century. The personal papers of Alan Greenwood and C.H. Waddington reveal that they actively utilised television and radio as forums for their work.

One of the earliest examples in the archives dates from 1936. Australian poultry geneticist Alan Greenwood‘s papers refer to two BBC radio broadcasts given by him titled ‘Junior Geography: the Empire Overseas’. There is also a copy of Greenwood’s script about the Australian outback for the Scottish Sub-Council for School Broadcasting, which begins ‘Good Afternoon, Boys and Girls – To-day we are going to make an excursion into the Australian Bush…’

C.H. Waddington supplemented his professional duties as lecturer, researcher, writer and director of the Institute of Animal Genetics with frequent appearances on television and radio, as his archives reveal. During the 1960s, for example, he participated in BBC broadcasts debating and discussing the existence of God, ‘the appearance of design in evolution’, Lysenkoism, and the social implications of biological research, most notably in the controversial programme ‘Towards Tomorrow: Assault on Life’, broadcast in December 1967. Waddington very much saw the biological sciences as woven closely into the fabric of society, with public debate an important facet of this. Writing to Waddington about his appearance on the BBC series ‘Some Aspects of Modern Biology’ in March 1967, science correspondent and adviser Gerald Leach wrote that ‘you were the only scientist that I’ve seen in this series who had any kind of feeling at all that one might set up social goals and try and work towards them.’

These ‘social goals’ are an important aspect of scientific research. Contentious as the media’s portrayal of science and scientists can often be, it puts a human face to specialist terminology, complex theories and vast data sets. It broadens our awareness of scientific discovery and its potential for the world and, importantly, allows us to respond.

Clare Button

Project Archivist

Research and Refugees – Edinburgh genetics during the 1940s

Last Friday I delivered a talk on genetics in Edinburgh during the 1940s as part of the Scotland-wide Festival of Museums, for which Edinburgh University Library and Collections took the 1940s as its inspiration. This was of course a turbulent decade for the world in general, but not least for the science of genetics. In the four decades since the rediscovery of Mendel’s laws in 1900, scientists were gaining a greater understanding of the gene through the chromosome theory of inheritance and mutation studies, yet the discovery of the structure of DNA itself was yet to be discovered. The 1940s represented a crossroads for genetics, and Edinburgh was an important world player in its future.

Let us begin in the year 1939, when Edinburgh’s Institute of Animal Genetics hosted the prestigious 7th International Congress of Genetics. Originally scheduled for Moscow in 1937, the repressive Stalinist regime made this impossible. After some discussion, Edinburgh was chosen as the most appropriate location for the Congress, now rescheduled for the last week in August 1939. Over 40 Russian scientists were to give papers, alongside delegates from all over the world. However, it would not be plain sailing. Shortly before the Congress was due to begin, the director of the Institute Francis Crew received word that the Russians had been forbidden to attend, and the Congress programme had to frantically reshuffled. Things went from bad to worse once the Congress actually began, as war erupted across Europe and delegates from various countries began to return to their home countries while they could. Once the Congress was over, Crew, who was on the Territorial Reserve of officers, was mobilised, and posted to the command of the military hospital at Edinburgh Castle. He left the Institute in the hands of poultry geneticist Alan Greenwood.

During the lean five years which followed, the Institute did its bit for the war effort. The land adjoining the Institute building was used for allotments for growing animal feed and planting vegetables. All male staff joined the ARP or Home Guard as well as the Watch and Ward parties for the protection of University buildings, while the women were involved in First Aid work. The annual report for 1940-41 records that everyone was given ‘a daily dose of halibut liver oil to reduce the incidence of winter colds’! Genetics teaching and research continued as much as possible by a skeleton staff, including Charlotte Auerbach, who would make a major scientific discovery during this period.

Charlotte (‘Lotte’ to her friends) Auerbach was from a scientific German Jewish family, and had sought refuge in Edinburgh after being dismissed from her teaching job in Berlin under Hitler’s anti-Semitic laws. Once established at Crew’s Institute, she had begun a developmental study of the legs of Drosophila, the fruit fly. But the arrival at the Institute of Hermann Joseph Muller in 1937 changed Auerbach’s career forever. Muller was the outstanding scientist of his generation: he had been part of Thomas Hunt Morgan’s famous ‘Fly Room’ at Columbia University in the 1910s, helping to formulate the groundbreaking chromosome theory; Muller’s later discovery that X-rays cause mutation, gained him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. But he arrived in Edinburgh a broken man after undergoing political and racial persecution in America, Germany and the Soviet Union. Muller had a radical effect on the staff and students at the Institute, and he quickly interested Charlotte Auerbach in mutation studies.

In 1940, the year Muller returned to America, Auerbach and her colleague J.M. Robson were tasked with conducting research into mustard gas. They were not told the true nature of the work, which had been commissioned by the Chemical Defence Establishment of the War Office. Auerbach reported sustaining horrific injuries to her skin from working with the gas with inadequate apparatus, but it shortly became clear that the results were astonishing for the science of genetics. Mustard gas caused mutations in similar ways to X-rays. Although this important discovery had to be kept confidential until after the war, Auerbach would be awarded the prestigious Keith Prize from the Royal Society of Edinburgh for the work.

Once the war ended, it was assumed that Crew would return to the Institute and that research would continue much as before. However, Crew felt he had been left behind by recent advances in genetics, and decided to transfer to the Chair of Public Health and Social Medicine at the University. Around the same time, the government were looking to move scientific research into areas of agricultural interest, following the acute food shortage crisis of the war years. It was decided to establish a National Animal Breeding and Genetics Research Organisation (NABGRO, later ABRO), and Edinburgh’s strong track record in genetics, animal breeding research and veterinary medicine made it the obvious choice. Conrad Hal Waddington, a developmental biologist and embryologist, was appointed director of the new Genetics Section of NABGRO, which moved to occupy the more-or-less empty Institute building. Alan Greenwood moved to become director of the newly-formed Poultry Research Centre, next door to the Institute.

ABRO’s work was to be split between research into fundamental work on genetics and the applied science of animal breeding and livestock improvement. However, conflict soon arose between the experimental geneticists and the animal breeders, which was not helped by the rather bizarre initial arrangement of Waddington, his staff and their families living together under one roof, taking their meals communally and driving to work together every day. As might be imagined, there were some scandals and arguments, and eventually the arrangement disintegrated and administrative shifts took place to accommodate the rift.

Waddington set about recruiting as many promising research workers as he could, including some of his old army contacts from his days in Operational Research and Coastal Command. One scientist who joined the Institute at this time, Toby Carter, had been in the RAF at the time of the fall of Singapore, and had commanded the only boat to escape towards Java. A diploma course in genetics was established, and laboratory space increased apace. By 1951, Waddington’s staff numbered 90 and the Institute grew to become the largest genetics department in the UK and one of the largest in the world.

By the time the 1950s arrived, molecular biology was on the horizon, paving the way towards advances in genomics and biotechnology which we see today. Edinburgh has consistently remained at the forefront of these advances, but it is interesting to reflect that early organisations such as the Institute of Animal Genetics and ABRO paved the way, and that the 1940s was a hugely important decade for this evolution.

Clare Button

Project Archivist

New Strides, Old Stripes: Zebras and the tsetse fly

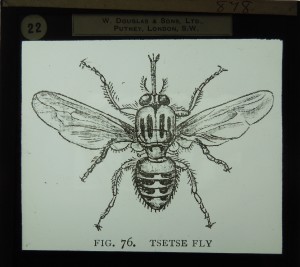

Glass slide, which probably once belonged to James Cossar Ewart, showing the tsetse fly (Coll-1434/3139)

It was announced last week that scientists have deciphered the genetic code of the tsetse fly, which offers hope of eradicating one of Africa’s most deadly diseases. The fly, which is only found in Africa, carries parasitic micro-organisms which cause sleeping sickness (trypanosomiasis) in humans by attacking their circadian rhythms (biological clock) and can be fatal if left untreated. As well as the threat to people, the tsetse can have equally devastating effects on animals, particularly livestock, causing infertility, weight loss and decrease in milk production. By also rendering animals too weak to plough, the consequences for farmers can be catastrophic. Since the parasite can evade mammals’ immune systems, vaccines are useless, and control of the tsetse is currently only achievable through radiation, pesticides or trapping.

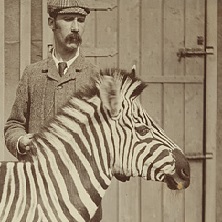

Concerns about the tsetse fly in Africa date from far before such advances in genetics could hope to help. There are several letters in James Cossar Ewart’s archives which give an insight into how the problem was being dealt with over a century ago. As you may remember from other posts, Ewart, Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh from 1882 to 1927, famously conducted cross-breeding experiments with zebras and horses on his home farm in Penicuik. It is perhaps not too surprising then, that zebras featured in Ewart’s thoughts about the tsetse fly…

Ewart’s letters show that between 1903 and 1909 he was corresponding with various individuals involved in the administration of East Africa (which was then a protectorate of the British Empire), where the tsetse fly was a great problem, particularly where animals such as horses – which were invaluable for transport – were being infected. Ewart believed his zebras could be the solution, if it could be shown that they were immune to the disease the fly carried. (Ewart had already been researching the potential of zebras and zebra hybrids as alternative pack and transportation animals in military, mining and agricultural contexts around the world). However, in June 1903, a letter from Ewart’s regular correspondent, the German animal dealer and trainer Carl Hagenbeck, regretfully informed Ewart that three zebras had died in Berlin after being infected. However, hope was not lost; a month later, Alice Balfour (sister of the 1st Earl of Balfour) wrote to Ewart wondering whether cross-breeding infected zebras with healthy horses might lead to an immune hybrid strain being created. As a matter of fact, zebras are indeed immune to the bite of the tsetse, with some theories holding that zebras have evolved stripes to confuse the flies and deter attack. In 1909, the author, soldier and hunter Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson wrote to Ewart stating that it was a shame zebras were not easily domesticated, as East Africa sorely needed animal transport immune from ‘the fly’.

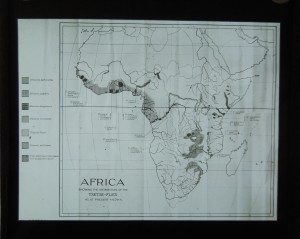

Glass slide, which probably once belonged to James Cossar Ewart, showing the distribution of the tsetse fly across Africa (Coll-1434/2058)

We don’t know from Ewart’s correspondence whether zebras did end up being used in East Africa, although they have remained useful to the present day – in 2010, for instance, it was announced that cattle in East Africa were being scented with zebra odour in order to deter the tsetse!

These letters offer an insight into ways of tackling the tsetse problem through species selection and cross-breeding before scientific advancement enabled the full sequencing of the tsetse genome.

Read more about the sequencing of the tsetse here:

http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/apr/25/scientists-crack-genetic-code-tsetse-fly-africa-sleeping-sickness

See the catalogue of James Cossar Ewart’s paper here:

http://www.archives.lib.ed.ac.uk/towardsdolly/cs/viewcat.pl?id=GB-237-Coll-14&view=basic

Clare Button

Project Archivist

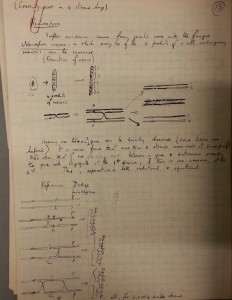

‘Riding High on a Spiral’

This Friday 25 April is ‘DNA Day’, an international celebration of the day in 1953 when James Watson, Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin and colleagues at Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, announced the discovery of the famous ‘double-helix’ structure of DNA. I thought this would be a good opportunity to look at some of the Watson and Crick-related material in the ‘Towards Dolly’ collections.

This Friday 25 April is ‘DNA Day’, an international celebration of the day in 1953 when James Watson, Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin and colleagues at Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, announced the discovery of the famous ‘double-helix’ structure of DNA. I thought this would be a good opportunity to look at some of the Watson and Crick-related material in the ‘Towards Dolly’ collections.

The C.H. Waddington collection contains a copy (GB 237 Coll-41/5/4/2) of Waddington’s review of James Watson’s book The Double Helix (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1968). Titled ‘Riding High on a Spiral’ and published in the Sunday Times, 28 May 1968, Waddington compares DNA to playing ‘a role in life rather like that played by the telephone directory in the social life of London: you can’t do anything much without it, but, having it, you need a lot of other things – telephones, wires and so on – as well’ and discusses the importance of Watson, Crick et al’s discovery in the wider context of the life sciences. However, he expresses concern at the purely intellectual and abstract nature of Watson’s work, with little practical familiarity with experimental material: ‘There is no evidence in the book that Jim Watson had ever seen any DNA, let alone started with ten pounds of liver, or whatever, and prepared it. It’s as though one wrote an account of the life of a musician who never did any practice.’

Waddington was certainly not one to mince his words, either in public reviews or private correspondence. This can also be seen in his 1974 correspondence (ref: GB 237 Coll-41/5/3/2) with Francis Crick, who was at this time working in the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge. What is particularly interesting about this correspondence is the spirited intellectual discussion – and disagreement – between the two scientists. Crick wrote to Waddington on 6 June 1974 asking Waddington to clarifiy some aspects of his ‘epigenetic landscape’, which Waddington had first proposed in 1957 as a way of visualising the development of a cell or group of cells in an embryo. He depicts the cell/s as a ball rolling down the ‘landscape’ and facing several ‘choices’ as to which way to go – just as the developing embryo is influenced down certain ‘paths’ by various genetic and environmental factors. In his letter, Crick admits to some difficulty in grasping exactly what certain aspects of the landscape might represent.

Waddington’s three-page reply to Crick is more than a little prickly, claiming that ‘it is a very simple and perfectly clear idea.’ Crick retorts on 28 June by stating that the concept seems ‘so vague as to be useless’ and that he would envisage the ball as ‘the lineage of a single cell of the adult animal’ rather than Waddington’s conception of it as ‘cell, tissue or pattern.’ Two weeks later, Waddington writes from his Italian holiday home that Crick seemed to ‘make such heavy weather of grasping the point’; the landscape model should not be applied to every dynamic system and the ball could represent either a single cell or a group of specialised cells. However, this reply still does not satisfy Crick. ‘It was nice of you to write at such length especially when you were on holiday’, he begins on 30 July. However, while the epigenetic landscape ‘may have been a useful idea in the Thirties’, Crick suspects that ‘it has long outlived its usefulness.’ Waddington has still not addressed his main issue, which is that the ball must represent a single cell in order to make sense, as the fertilised egg, ‘where it should all start’, after all is only one cell. His advice to Waddington about his idea? ‘Throw it away and start again!’

Almost a month later and back in Edinburgh, Waddington exasperatedly responds that ‘I should not leave you talking such nonsense without putting some reply on record’. As for the ball having to represent a single cell, he exclaims ‘for Heaven’s sake, why [?]’ He suspects Crick’s problem is his preoccupation with labelling single cells, tracing clonal descendants and ‘desperately – and not very successfully – looking for some questions that technique can answer. It’s your choice to follow that lead.’

Crick’s final reply in September 1974 is conciliatory: ‘Peace! Peace! I really am trying to get the most of your epigenetic landscape even if at times my manner gets a bit too brisk.’ He suggests that the two meet and discuss the matter face to face later in the year – an occasion where being a fly on the wall would have been quite enlightening!

Clare Button

Project Archivist

Lab Books

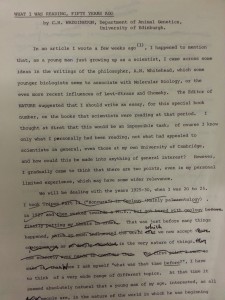

I have recently been reading about the ‘What Scientists Read’ project, which aims to explore the influence of literature and the arts upon scientific thought and practice. The project has interviewed scientists across the Scottish Central Belt with a view to establishing what their literary predilections and influences are, analysing the different genres discussed and their impact upon scientific work. This project reminded me of a draft of an article in our archived papers of Conrad Hal Waddington, the developmental biologist, embryologist and geneticist who was Director of the Institute of Animal Genetics, Edinburgh and Buchanan Professor of Genetics at the University of Edinburgh from 1947-1975. The article, titled ‘What I Was Reading, Fifty Years Ago’, was published under the title ‘Fifty Years On’ in Nature (Volume 258, Issue 5530, pp. 20-21) in November 1975, two months after Waddington’s early death. The draft typescript, marked with Waddington’s annotations and crossings-out, outlines some of his main literary influences during the years 1925-30 when Waddington was aged 20-25. This was at a time before seminal works by T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound changed the face of modern poetry, so Waddington at this time favoured ‘the English poets of the generation of Wilfrid Owen.’ He also had a keen interest in philosophy. From an early age, Waddington was heavily influenced by the philosopher A.N. Whitehead, lamenting that Whitehead ‘scarcely gets mentioned’, except in the context of being Bertrand Russell’s co-author of Principia Mathematica. Whitehead’s influence on Waddington strongly influenced his way of looking at the world, particularly his opposition to a division between mind and matter. Waddington felt that Whitehead ‘inoculated’ him against ‘the present epidemic intellectual disease, which causes people to argue that the reality of anything is proportional to the precision with which it can be defined in molecular or atomic terms.’

I have recently been reading about the ‘What Scientists Read’ project, which aims to explore the influence of literature and the arts upon scientific thought and practice. The project has interviewed scientists across the Scottish Central Belt with a view to establishing what their literary predilections and influences are, analysing the different genres discussed and their impact upon scientific work. This project reminded me of a draft of an article in our archived papers of Conrad Hal Waddington, the developmental biologist, embryologist and geneticist who was Director of the Institute of Animal Genetics, Edinburgh and Buchanan Professor of Genetics at the University of Edinburgh from 1947-1975. The article, titled ‘What I Was Reading, Fifty Years Ago’, was published under the title ‘Fifty Years On’ in Nature (Volume 258, Issue 5530, pp. 20-21) in November 1975, two months after Waddington’s early death. The draft typescript, marked with Waddington’s annotations and crossings-out, outlines some of his main literary influences during the years 1925-30 when Waddington was aged 20-25. This was at a time before seminal works by T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound changed the face of modern poetry, so Waddington at this time favoured ‘the English poets of the generation of Wilfrid Owen.’ He also had a keen interest in philosophy. From an early age, Waddington was heavily influenced by the philosopher A.N. Whitehead, lamenting that Whitehead ‘scarcely gets mentioned’, except in the context of being Bertrand Russell’s co-author of Principia Mathematica. Whitehead’s influence on Waddington strongly influenced his way of looking at the world, particularly his opposition to a division between mind and matter. Waddington felt that Whitehead ‘inoculated’ him against ‘the present epidemic intellectual disease, which causes people to argue that the reality of anything is proportional to the precision with which it can be defined in molecular or atomic terms.’

Waddington was also intrigued by thinkers who ‘brought literary criticism and philosophy very near together’, such as I.A. Richards and C.K. Ogden. ‘I doubt’, Waddington muses, ‘if, today, you would find anywhere the intimate interplay between poetry, philosophy and the foundations of science, which Ogden and Richards displayed.’ Waddington’s admiration for this interplay mirrored his own wide-ranging interests. From folk dance and music to art, architecture, ecology, computer science, robotics and more, science for Waddington was always closely integrated within, and informed by, all aspects of man’s life in society and upon earth. What comes across throughout the article is Waddington’s feeling that the flexibility of his interests was partly a product of his time: ‘[i]t was absolutely natural to have interests in philosophy, poetry, even painting, and to allow them to show. This was well before there was considered to be any firm dividing line between the natural or the moral sciences, or even between those and the Arts.’ This ‘dividing line’ between the arts and sciences, famously discussed in a famous 1959 lecture ‘The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution’ by C.P. Snow (incidentally a Cambridge colleague of Waddington’s) is one of the things which the current ‘What Scientists Read Project’ is attempting to combat. Waddington’s article provides an intimate glimpse into his intellectual background and how literature influenced his personality and his approach to science. No doubt ‘What Scientists Read’ will provide similar valuable insights as it progresses; I look forward to seeing the results.

More information on ‘What Scientists Read’ here: http://www.whatscientistsread.com/

Clare Button, Project Archivist

Picture Perfect!

Being lucky, as I am, to work with a wide variety of archival collections relating to the history of animal genetics in Edinburgh, it can be mightily difficult to select an all-time ‘favourite’ item. However, it was ‘make-up-your-mind time’ last month at the University of Edinburgh’s Innovative Learning Week, when myself and several colleagues from the Centre for Research Collections were invited to give a Pecha Kucha (a fast-paced and time-controlled) presentation on our favourite items or aspects of the collections with which we work.

Being lucky, as I am, to work with a wide variety of archival collections relating to the history of animal genetics in Edinburgh, it can be mightily difficult to select an all-time ‘favourite’ item. However, it was ‘make-up-your-mind time’ last month at the University of Edinburgh’s Innovative Learning Week, when myself and several colleagues from the Centre for Research Collections were invited to give a Pecha Kucha (a fast-paced and time-controlled) presentation on our favourite items or aspects of the collections with which we work.

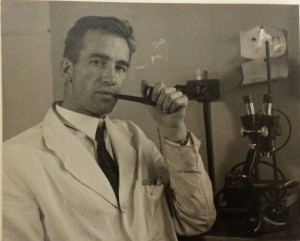

For me, there were a few strong contenders, but the ultimate winner had to be a photograph album presented to C.H. Waddington, the director of the Institute of Animal Genetics in Edinburgh, by his staff and students on the occasion of his 50th birthday in 1955.

The beautifully presented volume is still in perfect condition and contains a wonderful selection of photographs, all with careful names and annotations. The more formal portraits of staff and scientific researchers give a unique insight into laboratory and research work in the 1950s. In terms of white coats and microscopes, not much has changed today, but I’m not so sure about this suave example of pipe-smoking!

The album also contains pictures of individuals who don’t always feature in the official histories of Edinburgh’s animal genetics community, including the scientists’ wives. The Institute was sometimes rumoured to be a hotbed of scandal and intrigue, so one would like to have been a fly on the wall at this particular party…

I also love the informal and humorous photographs in the album, which paint a much more individual and human picture of the geneticists’ lives and working environment than can be gained simply through printed papers, research reports and official correspondence. Who can fail to be inspired by pictures of an amateur ballet based on the fruit fly Drosophila, for example?

You can watch a video of the Pecha Kucha here: http://vimeo.com/87273640

A Passage to India: J.B.S. Haldane and the Journal of Genetics

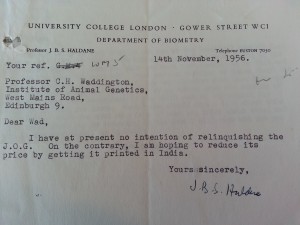

The C.H. Waddington collection contains a folder of correspondence with J.B.S. Haldane, who died 50 years ago this year, concerning the Journal of Genetics. The correspondence, which covers 1956 to 1957, expresses Waddington’s concern at the decision made by Haldane to take the Journal, of which he was editor, out to India with him when he retired.

The C.H. Waddington collection contains a folder of correspondence with J.B.S. Haldane, who died 50 years ago this year, concerning the Journal of Genetics. The correspondence, which covers 1956 to 1957, expresses Waddington’s concern at the decision made by Haldane to take the Journal, of which he was editor, out to India with him when he retired.

The Journal of Genetics had a long-standing, although somewhat fraught, relationship with Edinburgh’s Institute of Animal Genetics. Established in 1910 by two men who could be called the ‘founding fathers’ of the science in Britain, William Bateson (who coined the term ‘genetics’ to encompass its present scientific meaning), and Reginald Punnett (who held the first Chair of Genetics in Britain), it is the oldest English language journal in that field of science. However, in its first few decades it was felt to be inaccessible and somewhat limited in its publication remit by certain more experimental scientists, including those at the Institute of Animal Genetics. This was so much the case that the Institute’s director, F.A.E. Crew and his colleagues at the Institute, Julian Huxley, Lancelot Hogben and others, teamed together in 1923 to establish the Journal of Experimental Biology along with an associated Society of Experimental Biology. As hinted at in its title, the new Journal aimed to publish papers of a more experimental nature covering a wider range of genetical and evolutionary biology theories and hypotheses than covered by the Journal of Genetics at that time.

However, when editorship later passed to physiologist, geneticist, mathematician and general polymath J.B.S. Haldane, his remarkable breadth of interest and abilities and sharp, colourful personality transformed the Journal’s remit and potential (although Waddington claimed he was ‘a rather niggling editor about details and notoriously bad at answering letters’ [part of GB 237 Coll-41/5/2/9 ]).

However, when Haldane decided to retire to India in the late 1950s, where he would become a naturalised citizen, his decision to take the Journal with him caused some consternation in Britain. Waddington, who was Crew’s successor as director of the Institute of Animal Genetics, felt that the editorship should pass over to him and his colleagues and that for Haldane to continue in India would be ‘chaotic’. But Haldane would not be dissuaded, writing with characteristic wryness to Waddington on 19 January 1957:

You can, of course reply that I am an old man and may soon die or lose such intellectual powers as I still possess. I may. But my systolic pressure is 120-130mm Hg. And I have not lost a day’s university teaching through illness since 1930. And meanwhile a thermonuclear bomb or a major economic crisis may affect British publication. When I die or become too senile to edit, there need be no more difficulty in transferring the Journal back to Britain than in transferring it to India.

(part of GB 237 Coll-41/5/2/9).

Following Haldane’s death in 1964, his widow Helen Spurway continued publication in India with Madhav Gadgil, H. Sharat Chandra and Suresh Jayakar until she died in 1977. In 1985, the Indian Academy of Sciences resumed publication of the Journal, which still continues to this day in association with Springer publishing.

Look out for a longer piece here on J.B.S. Haldane late this year!

The Hen Who Made History…Nearly

Edinburgh holds a number of world records in genetics and animal breeding, which, considering its historic significance in the history of the science in Britain, is not all that surprising. Its most famous ‘first’ is of course Dolly the sheep – the first mammal to be cloned from adult cells – although there are many other examples. However, sometimes the ‘almost firsts’ are just as interesting historically, as well as a little poignant, as I found recently when cataloguing the archive of Alan Greenwood, director of the Poultry Research Centre from 1947 to 1962.

Amongst his wonderful collection of photographs is one depicting a hen standing proudly astride crates and baskets of eggs. The caption informs us that the hen is ‘the sister of the hen which laid 1515 eggs in 9 laying years and shared the world’s record.’ This was intriguing enough in itself, but a full explanation wasn’t forthcoming until I came across two typed pages in Greenwood’s collection of draft lectures and articles. Titled ‘So Near and Yet So Far’, this short piece describes the particularly productive life of the chicken named L1641, ‘from which so little and yet so much more was hoped.’

Part of the research carried out at both the Institute of Animal Genetics and the Poultry Research Centre in Edinburgh was concerned with increasing the productivity and economic value of domestic animals by applied genetics and breeding schemes. In the case of chickens, a large aspect of their value clearly lies in the number and quality of eggs they produce. On 10 April 1939 however, a chicken was hatched at the Institute which would push the limits of egg production beyond the expectations of the staff.

Chicken L1641 (as she was wingbanded) laid her first egg soon after the outbreak of the Second World War. From her first year she was a high producer, laying 273 eggs ‘in spite of wartime stringencies’ as Greenwood wryly tells us. Over the next 8 years she produced on average 142 eggs per year. This is high, although not as impressive as the hens which held world records for the number of eggs laid in a single year. In 1915 a white Leghorn hen in Greensboro, Maryland by the name of Lady Eglantine set a record at 314 eggs in one year. A number of Australorp hens in Australia broke this record successively during the 1920s however, with the number of eggs in one year standing at 347 to 354 to 364!

Where Edinburgh’s chicken L1641 excelled, however, was in the total number of eggs produced over a lifetime. By the time she went into moult in the autumn of 1948, she held the joint world record, which stood at 1515 eggs. However, the strain imposed on her calcified and thickened arteries by the moult was too great, and she died before the end of the year. As Greenwood sadly concludes his article, ‘One more egg only and she would have made history.’

Alan Greenwood’s catalogue can be viewed on our brand new website at: http://www.archives.lib.ed.ac.uk/towardsdolly/

Geoffrey Herbert Beale

Two weeks ago, when we posted about the Lysenko Controversy in Soviet Russia, mention was made of Geoffrey Beale’s interest in and knowledge of the Russian language and scientific history. Beale was based at the Institute of Animal Genetics in Edinburgh from 1947 until 1978 and is best known as the founder of malaria genetics. His personal archive, which takes up some 40 boxes and contains notebooks, correspondence, publications and drafts, is currently being catalogued here in Edinburgh University Library Special Collections, so a brief biography may be in order to shed some light on this humane and fascinating man.

Two weeks ago, when we posted about the Lysenko Controversy in Soviet Russia, mention was made of Geoffrey Beale’s interest in and knowledge of the Russian language and scientific history. Beale was based at the Institute of Animal Genetics in Edinburgh from 1947 until 1978 and is best known as the founder of malaria genetics. His personal archive, which takes up some 40 boxes and contains notebooks, correspondence, publications and drafts, is currently being catalogued here in Edinburgh University Library Special Collections, so a brief biography may be in order to shed some light on this humane and fascinating man.

Beale, born in Wandsworth, London in 1913, developed a keen interest in Botany while a student in Imperial College, London, despite his parents’ opposition to a scientific career (he was even made to sit a psychological examination which recommended that he become a tax inspector instead!). In his third year of university, Beale completed a summer course in plant genetics given at the John Innes Horticultural Institute, which would shape the course of his future career. Beale was eventually offered a job at the John Innes, receiving his PhD in 1938 and studying, among other things, the chemistry of flower colour variation until being called up to the army in 1941.

Due to having what he called a ‘smattering’ of languages, including Russian, Beale was drafted into the Intelligence Corps (Field Security) and posted to Archangel and then Murmansk, Russia, where he had the opportunity to improve his Russian. Beale was awarded an MBE for his military service in 1947.

After the war, Beale wondered how he would get back into science after his five year absence. Fortunately, he was offered a job at Cold Spring Harbor working with Escherichia coli. Beale also worked for a spell with geneticist Tracy Sonneborn at Bloomington, Indiana, and it was then Beale developed his lifelong interest in the protozoan Paramecium. The award of a Rockefeller Fellowship necessitated his return to the UK in 1947, where he was duly offered a lectureship by C.H. Waddington, who had just arrived in Edinburgh as director of the genetics section of the National Animal and Genetics Research Organisation within the Institute of Animal Genetics. At the Institute, Beale became close friends with Henrik Kacser and Charlotte ‘Lotte’ Auerbach, about whom he would later write an account, and gained funding to design and build dedicated research laboratories, including the Protozoan Genetics building for his research group. This group worked on the genetics of Paramecium and on protozoan parasites, and attracted visiting scientists from all over the world. Beale was appointed a Royal Society Research Professor in 1963, a position he held until his retirement.

In the mid-1960s, Beale developed an interest in malaria genetics, gaining a grant from the Medical Research Council in 1966. Together with programme leader David Walliker, who would become a renowned malariologist, they established a mosquito colony, built an insectary, collected parasite strains and established rodent facilities for African tree rats. The work of another researcher, Richard Carter, helped establish the parasite genetic markers, and the foundations of genetic analysis in malaria parasites were laid. Later research covered the genetic analysis of drug resistance, virulence and the classification of rodent malarias into species and subspecies. He continued his malaria work during a six month visiting professorship at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, establishing a collaborative research programme with Professor Sodsri Thaithong as well as a malaria research laboratory which achieved World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre status. This phase of Beale’s career laid the groundwork for many other scientists working on parasite diversity and genetics. In 1996 Beale was awarded an honorary DSc from Chulalongkorn University, one of the first foreigners to be so honoured.

Beale married Betty MacCallum in 1949 (they were divorced in 1969) and he would often take their three sons to the laboratory with him on Sundays where they would learn about science and film printing techniques. Beale continued to work at the laboratory every day well after his retirement. After 1998 he began work on a new book on Paramecium to show the advances and new directions of research in the area. However, his health was deteriorating and much of the later writing was done by co-author John Preer. The book, Paramecium: Genetics and Epigenetics, was published in 2008, when Beale was 95 years old. Geoffrey Beale died in Edinburgh on 16 October 2009.

We’ll be posting up items of interest from the Beale collection as cataloguing progresses, with the finished catalogue being mounted online on our newly-launched project website at: http://www.archives.lib.ed.ac.uk/towardsdolly/

References:

J. R. Preer Jr and Andrew Tait, ‘Geoffrey Herbert Beale MBE’, Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, 57: 45-62 (2011)

Geoffrey Beale, ‘Autobiograpy (written July 1997)’, in Coll-1255, EUL Special Collections.