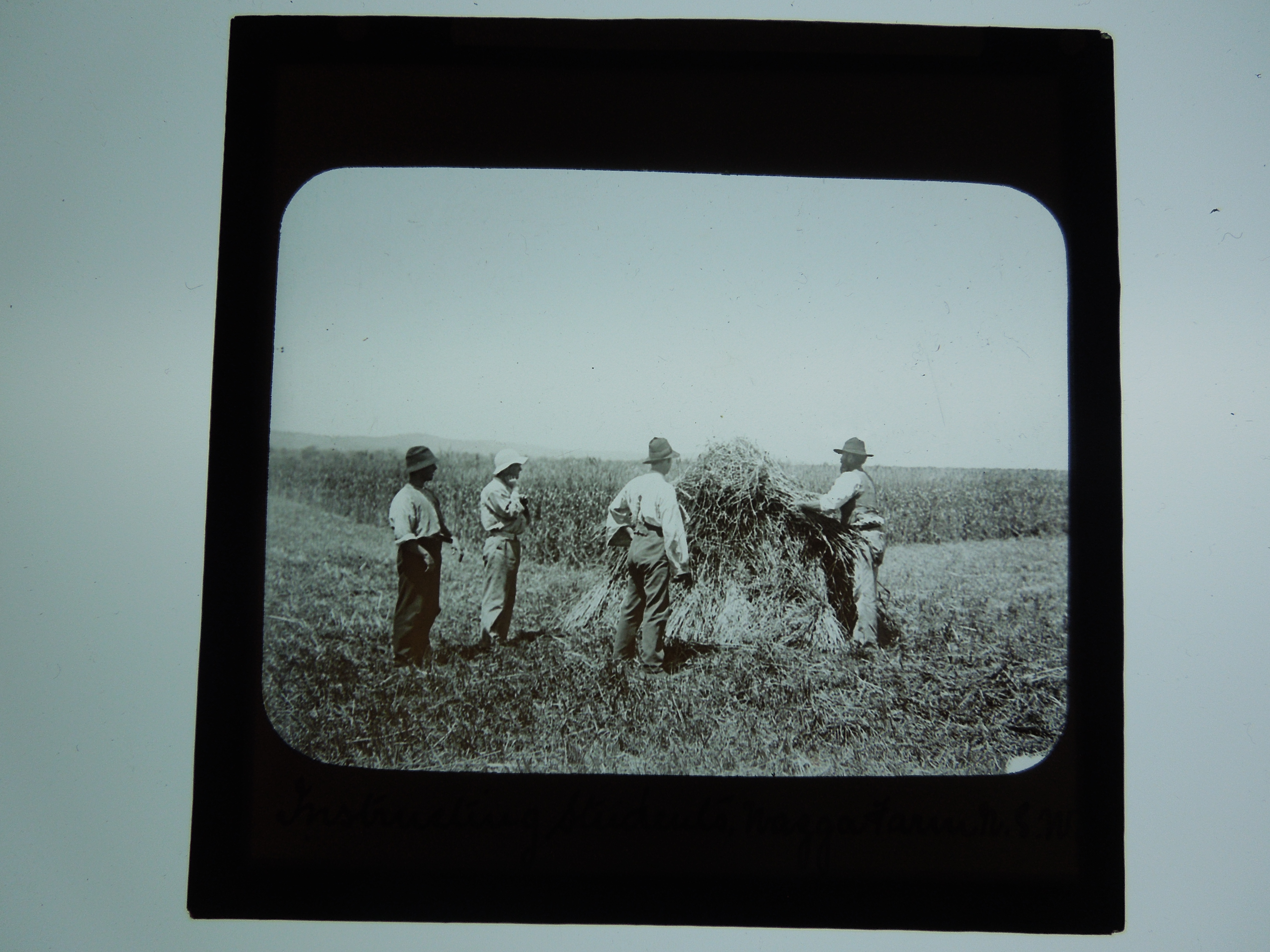

While I’ve been busy cataloguing the scientific off-prints from the various institutes that have comprised the animal genetics programme in Edinburgh; with the start of the New Year I am moving on to catalogue the glass plate negative slide collection that makes up another aspect of the Towards Dolly project. There are c4000 glass slides, which we think were used as teaching materials, covering images of animals, plants, farming techniques and machinery from places like Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South East Asia among other places.

First, though, I’d like to tell you a bit about what a glass plate slide is and a bit of its history in regards to photography. The first collodion wet plate negative was made by the British photographer, Frederick Scott Archer in 1851 and Richard Leach Maddox, a British physician and photographer, made the first dry glass plate negative twenty years later in 1871. What is meant by these types of negatives? ‘Glass plate negatives comprise two formats collodion wet plate negatives and gelatin dry plate negatives. Both types have a light sensitive emulsion with a binder thinly layered on one side of a glass plate.’ The article, Handle with Care: Glass Plate Negative and Lantern Slide Collections at the Syracuse University Archives, is particularly useful in describing the history and technique.

Since I’m just beginning to catalogue the glass slides collection and have already found many interesting and diverse images – from a photograph of men loading horses in the Chicago Stockyards:

to an illustration of man-eating lions from Tsavo (Kenya) :

– I’m looking forward to discovering more fascinating things as time goes on. I’ll keep you posted!