This week the exhibition curator, Laura Moretti, of the University of St. Andrews, writes about the finest, and probably most famous book in our selection: Andrea Palladio’s “Four Books of Architecture”.

Andrea Palladio, I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura, (Venetia: Dominico de’ Franceschi, 1570) (University of Edinburgh Library, Special Collections, Smith.1594)

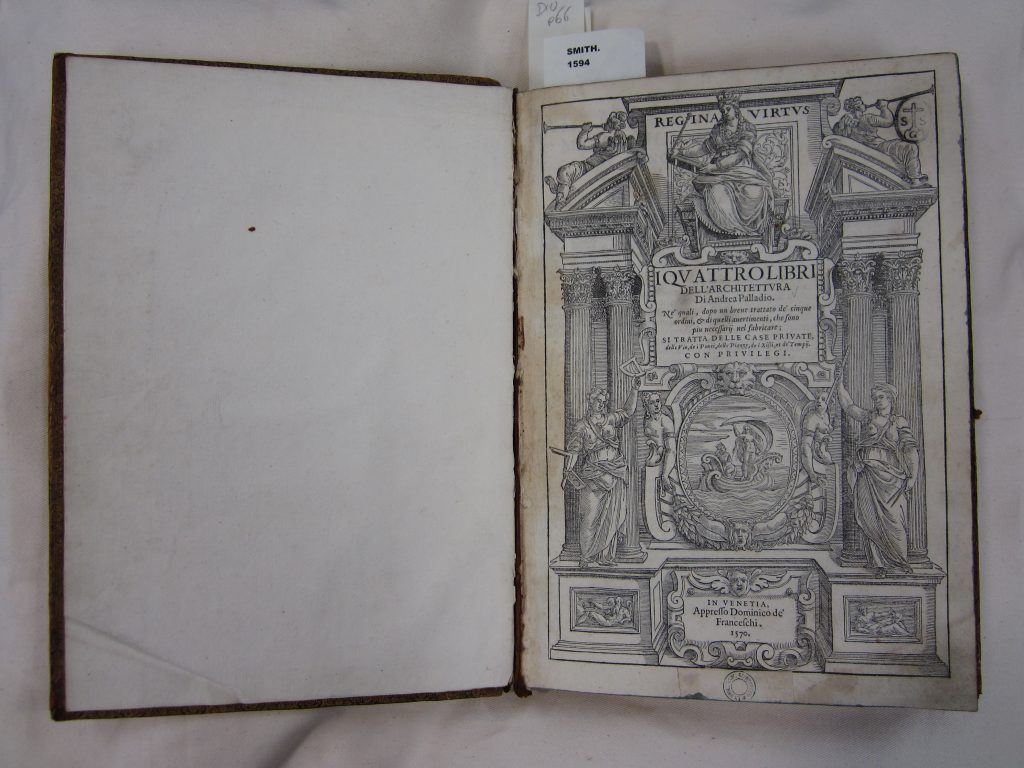

Andrea Palladio (1508-80) first published his I quattro libri dell’architettura in Venice in 1570, in the printing shop of Domenico de’ Franceschi (fl. 1557-75), publisher and book dealer from Brescia, at the sign of “Regina Virtus” in the Frezzeria. The book enjoyed extraordinary fortune, through its numerous editions and translations, becoming the main channel of the widespread knowledge and appreciation of his author’s work.

Title page detail

Palladio already had important experience in the field of book publishing. In 1556, Daniele Barbaro – a refined and sophisticated Venetian patrician, and already the architect’s patron and supporter – put through the press a translation with commentary on the architectural treatise of the Roman author Vitruvio, complemented by Palladio’s lavish illustrations.

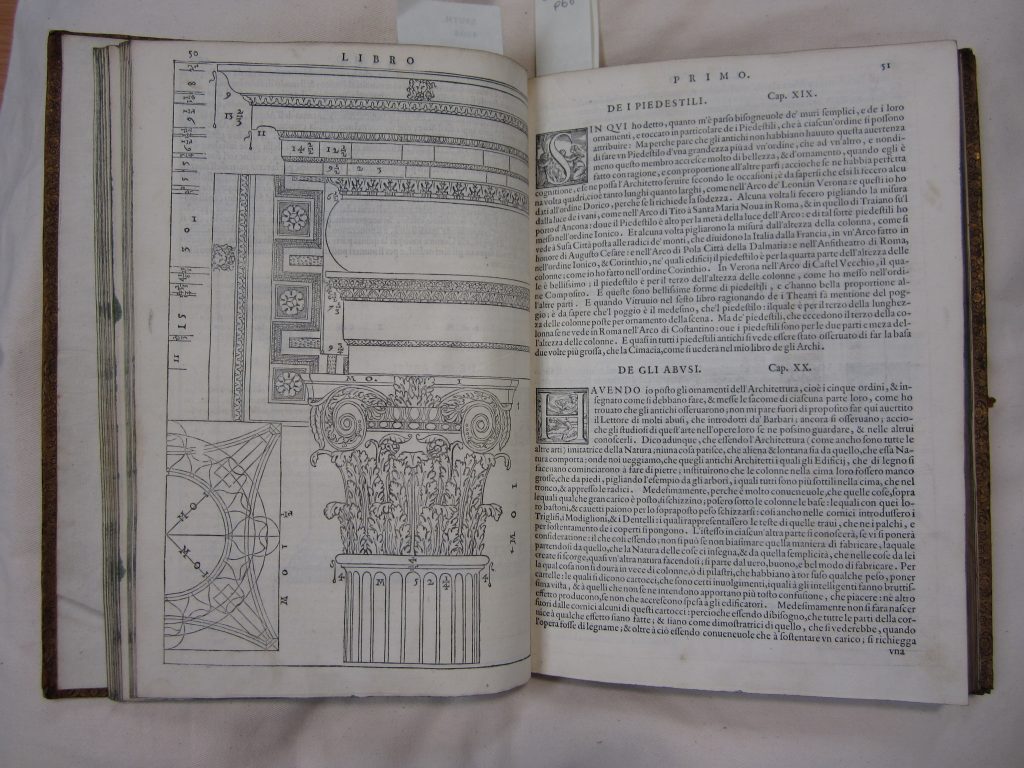

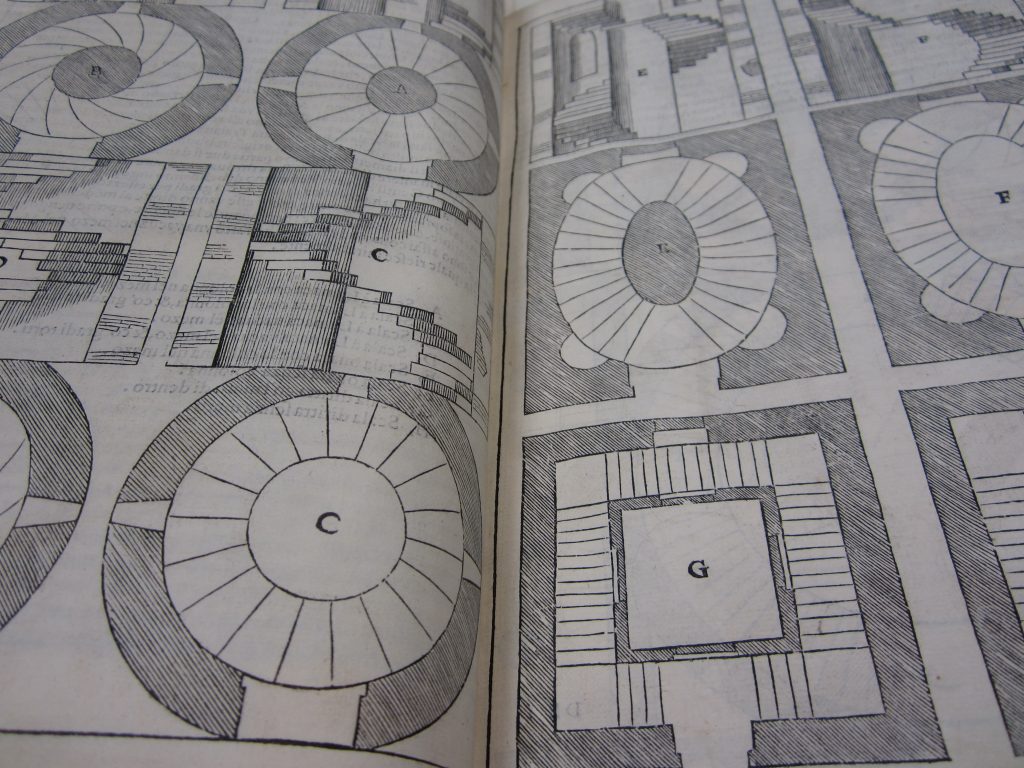

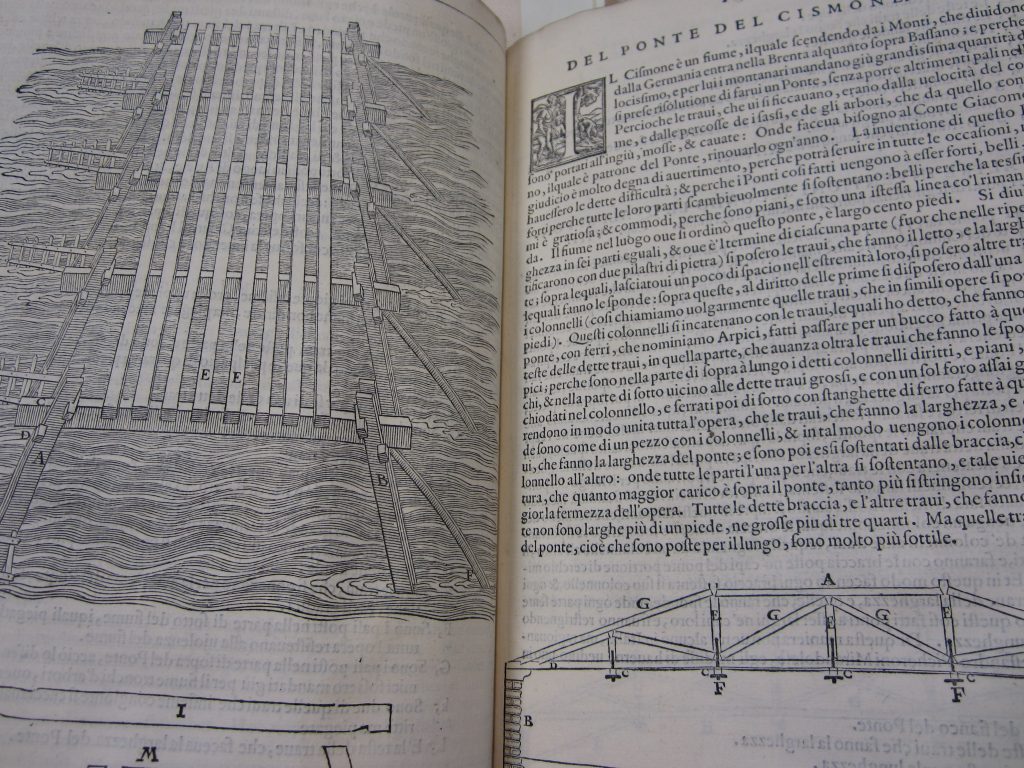

In Palladio’s treatise, the subject matter is subdivided in four sections: the first book – dedicated to a friend and patron, the Vicentine Count Giacomo Angarano – discusses the fundamental principles of building and the five architectural orders; in the second book Palladio presents his portfolio of projects for residential palaces and country houses, and reconstructions of ancient Greek and Roman houses; in the third book – dedicated to the Prince Emanuele Filiberto Duke of Savoy (1528-80) – the architect treats roads, bridges, squares, basilicas and other public buildings; while the fourth and final book is dedicated to antique temples in Rome and elsewhere, in the Italian peninsula and beyond. Book One, Book Three, and Book Four also contain introductory letters to the readers.

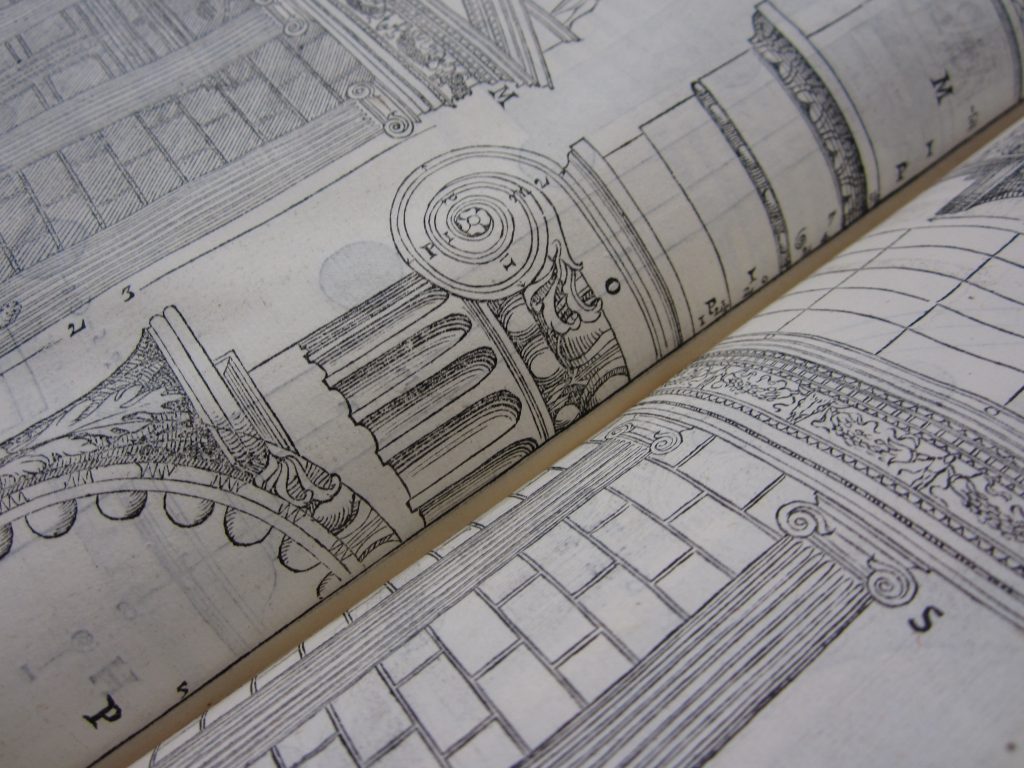

Book 1. The Composite Order

Book 1. Stairs

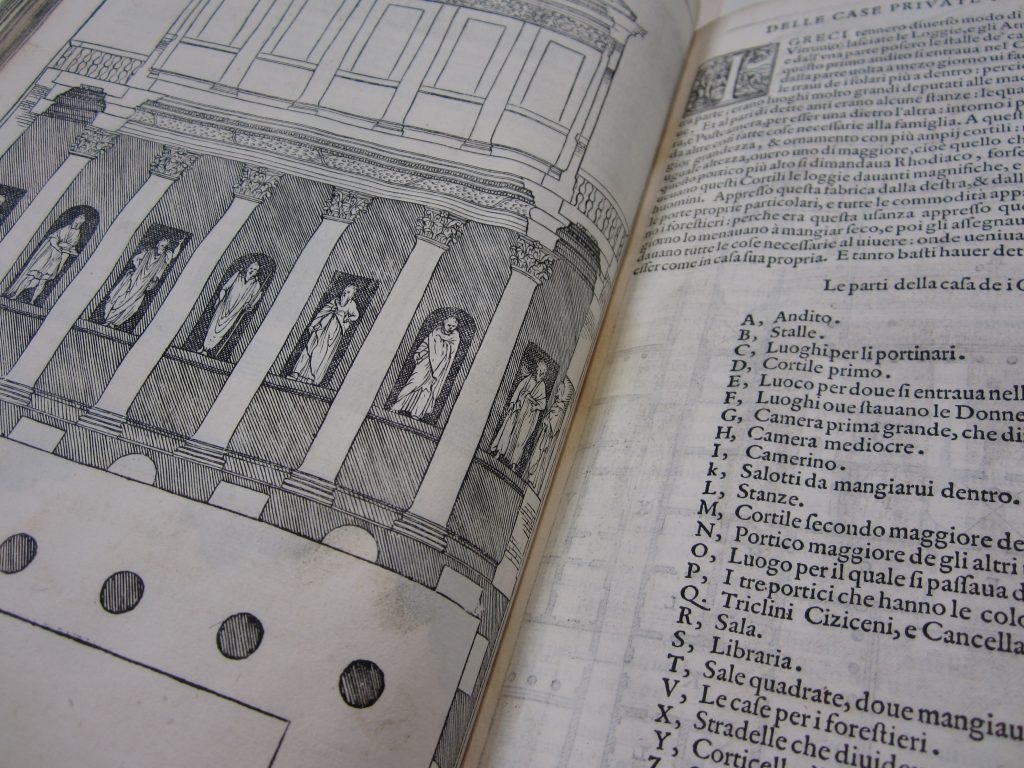

Book 2. House of the Greeks (detail)

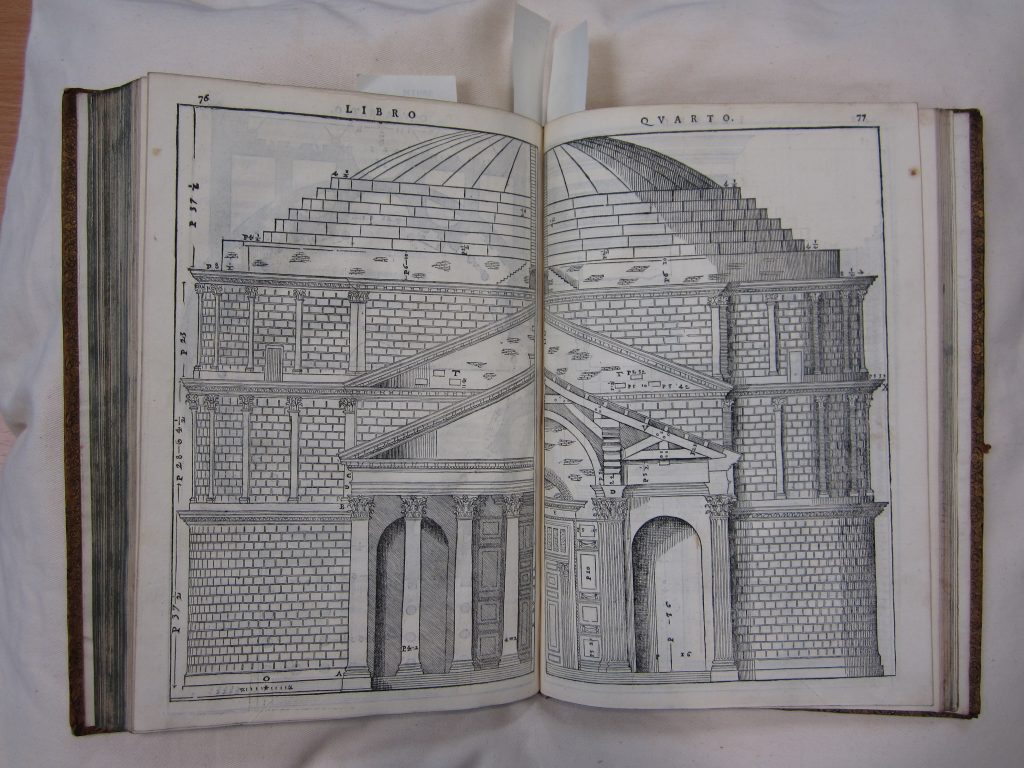

Book 4, detail of the Temple of Portunus

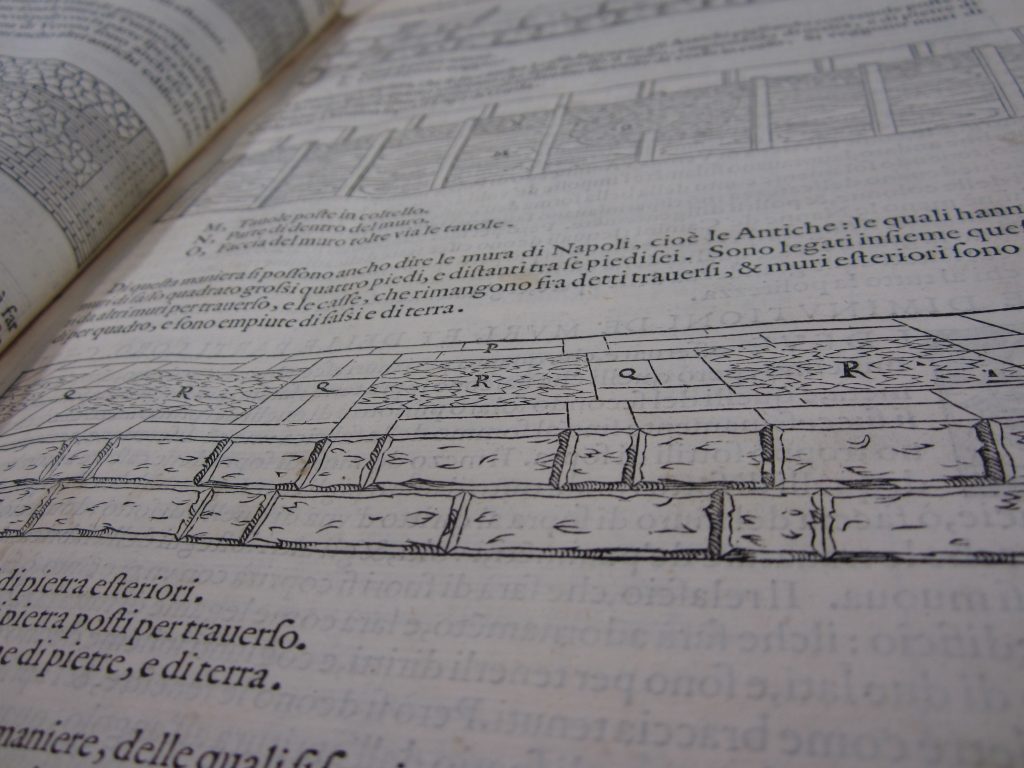

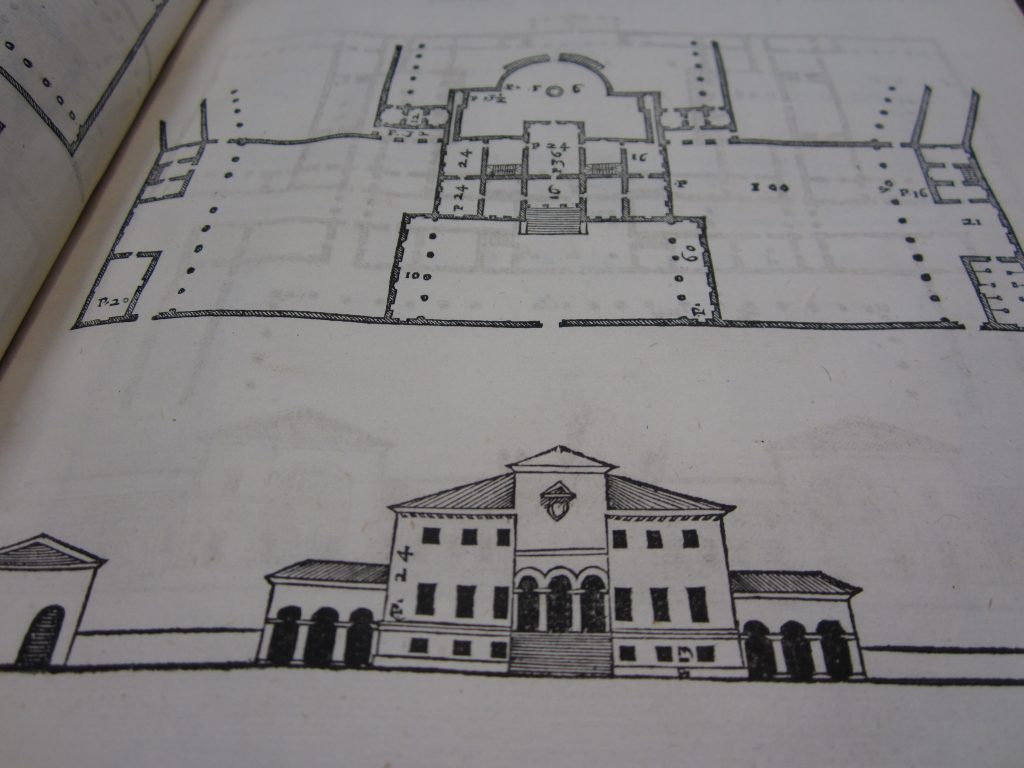

The edition is finely illustrated: all the books are introduced by a full-page woodcut and illustrated by numerous diagrams and architectural details. The relationship between words and image is heavily weighted towards the latter. The text is often used to explain and elucidate the drawings, and frequent lists referring to corresponding details in the illustrations provide precise terminology and further interpretations. The drawings frequently present measurements, which give a clear sense of the proportions between different architectural elements. Palladio very rarely makes use of perspective: the only exceptions are constituted by the description of brick courses and layers in Book One, and the representation of Caesar’s Rhine bridge in Book Three.

Book One, detail of brick courses.

Book 3. Detail of Caesar’s Rhine Bridge

The majority of the drawings are plans, elevations or sections, variously articulated in the page layout. Contextual elements defining the buildings’ surroundings are rare and limited to some schematic representations of water and occasional exemplifications of soil. Shadows are consistently employed to confer profundity to the architectural elements, from the depiction of minute details to the outlines of massive buildings. The potentialities of the medium are fully explored and used at their best.

Book 4. The Pantheon

While in the depiction of ancient buildings Palladio shows an obsessive attention to the accuracy and faithful rendering of detail, the representations of his design projects present elements of greater complexity. More than faithful copies of the completed buildings, they seem to be idealizations, perhaps the architect’s successive reflections or maybe the sign of ideas not fully executed.

Book Two, Villa Godi, Lonedo di Lugo di Vicenza

The copy now preserved at the University of Edinburgh comes from the library of Adam Smith FRSA (1723-90), the Scottish economist, philosopher and author, and a key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment era. The University of Edinburgh holds about half his original library (850 works in 1,600 volumes), including books on politics, economics, law and history, but also many literary works, particularly French literature, and books on architecture.

The full catalogue record for our copy can be found here: https://discovered.ed.ac.uk/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=44UOE_ALMA21147069860002466&context=L&vid=44UOE_VU2&search_scope=default_scope&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US