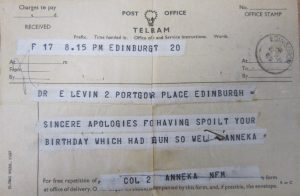

Parts of this collection are a veritable Wunderkammer or ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’. Within Ernst Levin’s collections, as is the case with the personal files of any individual, there are items which completely defy any attempt at explanation. There are also objects which are absolutely fascinating, though not perhaps of obvious value for use in historical research. They represent an example of material culture, in that they passed through family hands and are a collection of things curated by the individual which demonstrate their taste. Below are some examples of the miscellaneous treasures to be found amidst the carnage of an uncatalogued personal archive, this one being donated to Lothian Health Services Archive housed in twenty old boxes.

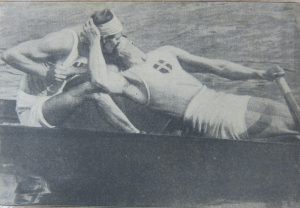

Magazine clipping circa 1920s of two male rowers kissing. This clipping is an exact outline of the photograph shown below but also the reverse side, which shows fashionably dressed women. There is uncertainty as to which image the clipping was extracted for, but Anicuta was certainly of liberal inclination.

Anicuta as a young girl in Communion dress for the Catholic ceremony. The decadence of her clothing demonstrates a considerable degree of wealth.

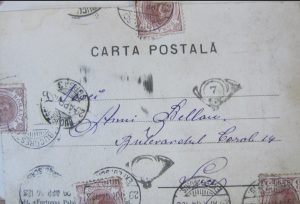

The family Belau pose for a photograph in Bucharest around 1900. Anicuta’s father Paul was an architect and designer: postcards sent from him in Buenos Aires and Cuba suggest that he was often abroad.

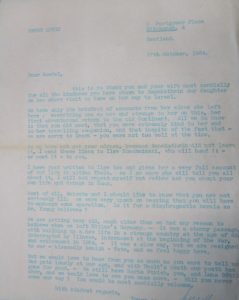

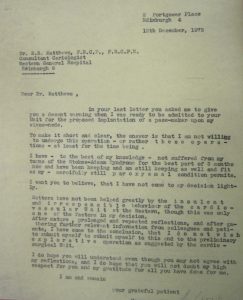

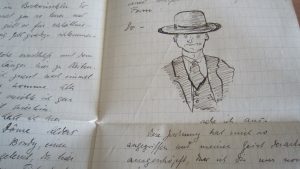

Anicuta and her artist friends often illustrated their correspondence to each other, producing vibrant letters with doodles covering the pages.

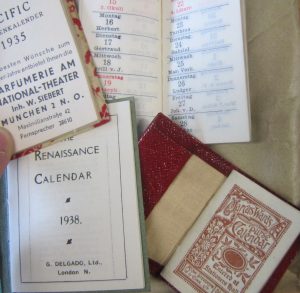

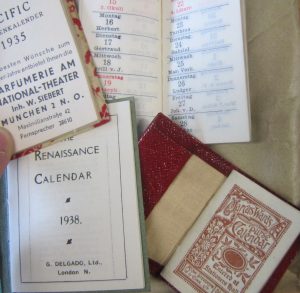

Anicuta was the owner of infinite tiny notebooks and pocket calendars, some expensively bound in adorned material.

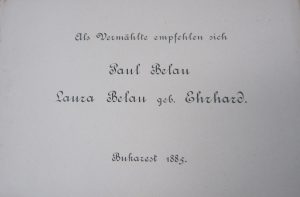

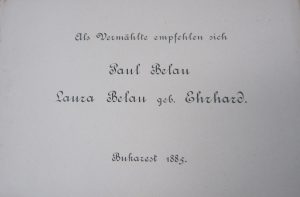

An invitation to the wedding of Laura and Paul Belau, Anicuta’s parents, in 1885.

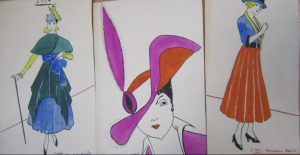

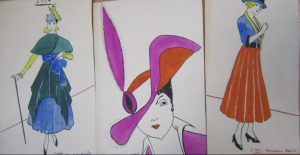

Anicuta’s sketches: she attended art school in Utrecht during the 1910s.

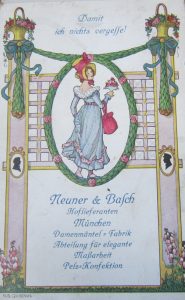

Anicuta’s coloured drawings of stylish women: she maintained an ardent interest in fashion.

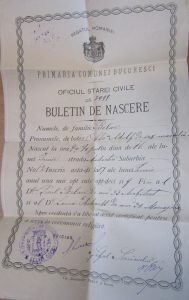

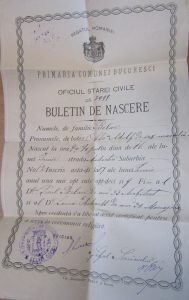

Birth certificate of one of Anicuta’s siblings, in Romanian.

Japanese-style fabric-covered box containing an extensive series of original love poetry, typed and hand-written. Sent from a man who may have been Anicuta’s sweetheart prior to marriage, between 1904 and 1906.

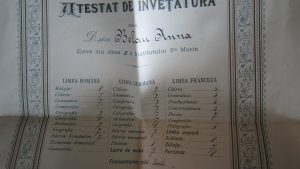

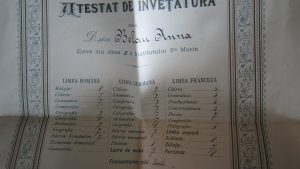

The report card of Anicuta Belau from her high school in Bucharest: she is graded for various subjects in French, Italian and German.

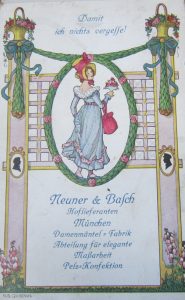

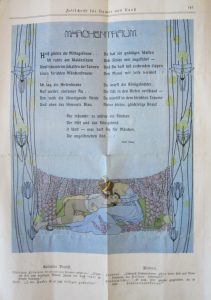

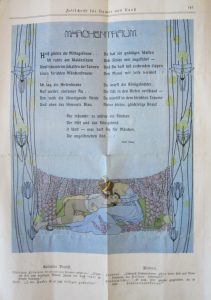

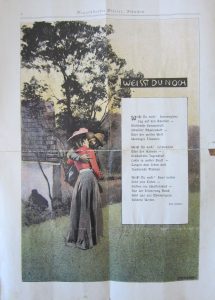

Pages from an Art Nouveau magazine:

First page depicts an art nouveau illustration and a poem called ‘Maerchentraum’ (Fairy-tale dream):

‘The midday sun was burning hot…

I was resting in the forest

And dreamt in the shade of the trees

A foolish fairy-tale dream:

I, a shepherd boy

Lay alone …

Around me the silent moor

And above me the blue sky

Then some kind God lead

You proudly to me

And with quivering lips

You quietly kissed my mouth

You were the King’s daughter

Who fell in love with the shepherd boy –

You were in my foolish dream

My young, happy bride ..

I dreamed: they were together

The shepherd and the Princess

O world – what fairy-tales you have

That have never been written down .. !

– Ernst Staus’

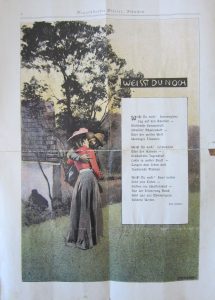

The other is entitled ‘Weisst Du Noch’ (Do you remember):

‘Do you remember? Sunshine

Shone on the trees –

Sizzling summer air

The heavy scent of Acacia –

Across the wide world

Delightful dreams.

Do you still remember?

The song of the skylarks

Over the plants –

Joyful youthful air…’

Set of Anicuta’s intricate tiny pocket calendars, 1936-38.

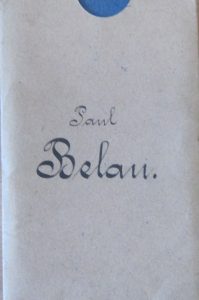

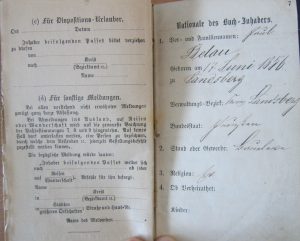

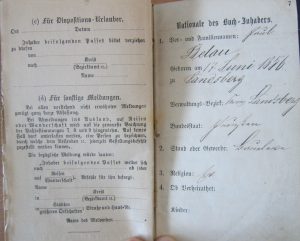

Paul Belau’s military pass: Anicuta’s father Paul Belau was an architect and designer who spent a lot of time in Buenos Aires, also co-designing a building in Havana, Cuba: https://structurae.net/persons/paul-belau. His military pass is in German, dated 1877. The family was of German origin but relocated to Bucharest, Romania, where Anicuta spent her youth.

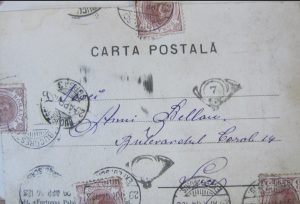

Postcard to Anicuta Belau in Bucharest, 29th April 1904, with colourful three-dimensional fan detail.