On this day, 30 June, in 1940 the Germans invaded the Channel Islands which was the beginning of nearly 5 years occupation. In this week’s blog I’m using some of the Library’s online resources to find primary source material to discover more about this facet of the Second World War.

I recently had the opportunity to visit the Jersey War Tunnels, one of Jersey’s many tunnel complexes built by mostly forced and slave labour under German command during the occupation.I have to admit that before that visit I really knew very little about this period in the Channel Islands history but I was inspired by the incredibly moving and fascinating exhibition to try and find out what primary source material was available to us through the University Library’s fantastic online primary source collections about the occupation.

© Mark Cairney

There are many stories that could be told about the Channel Islands occupation and I encourage you to seek them out but due to the nature of our online primary source collections and time limits I’m focusing on what the outside world, mainly Britain, knew (or didn’t) about what was happening on the Channel Islands during the occupation.

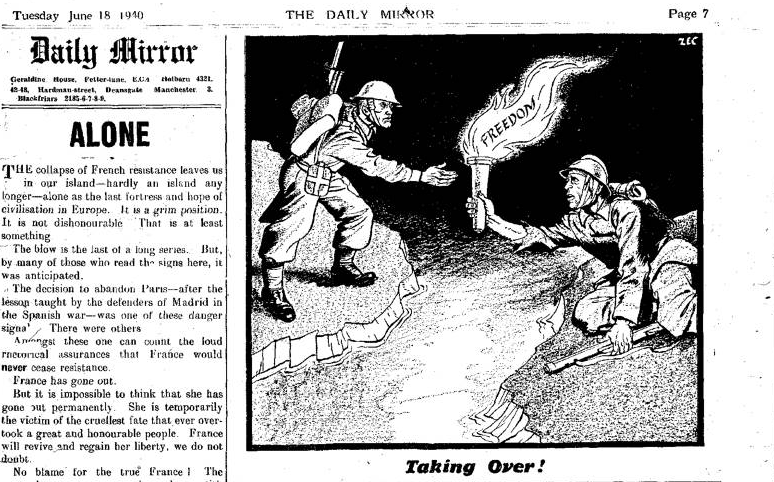

The blitzkrieg nears Britain

The first half of 1940 was a dark time for the Allies in the Second World War. In fairly quick succession Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands and France were invaded by Germany. With the evacuation at Dunkirk (Operation Dynamo) and France, faced with no real other choice, signing an armistice with Germany in June of that year, Britain was now on its own and under threat.

The Daily Mirror, Tuesday, 18 June 1940, p. 7. UK Press Online. Accessed 25th May 2018.

The Channel Islands, Crown dependencies of the United Kingdom and just off the French coast, were particularly vulnerable at this time.

The Channel Islands consist of four larger islands Jersey (the largest), Guernsey, Alderney, and Sark with a number of smaller inhabited and uninhabited islands. The islands are not part of the United Kingdom and have their own local administration but the inhabitants are British citizens.

“Repugnant” and “distasteful”: abandoning British territory

On 19 June the War Cabinet agreed that the Channel Islands would be demilitarised and therefore unprotected despite the fact it was “repugnant now to abandon British territory” and “distasteful…especially as it gave the enemy an opportunity of claiming that he had occupied British soil”. [1]

Once the local authorities on the islands had been informed the British would not be defending the islands they had to urgently make provisions for those who wanted to evacuate. The islanders were not given very long to decide if they wished to leave and if they did decide to evacuate they could take very little with them, leaving homes, businesses and belongings behind.

The Daily Mirror, Monday, 1 July 1940, p. 3. UK Press Online. Accessed 4th June 2018.

In the end while 1000s of islanders did evacuate to the UK (with Alderney becoming virtually uninhabited), many remained to face whatever was coming their way.

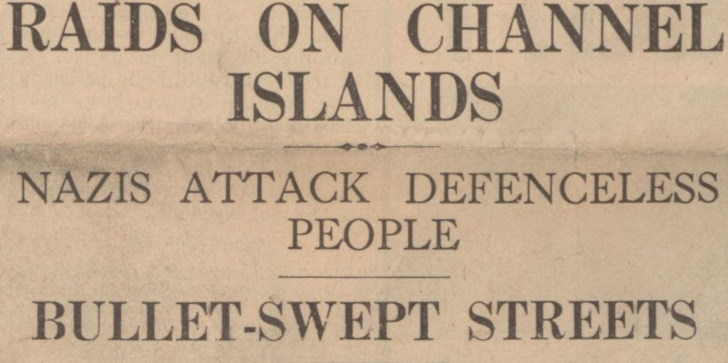

They didn’t have to wait long. On 28 June 1940 the Germans bombed harbours in Jersey and Guernsey, killing 44 people.

Derby Daily Telegraph, Saturday, 29 June 1940, p. 1. British Library Newspapers. Accessed 8th May 2018.

Unfortunately news of the decision to demilitarise the islands had been suppressed and this information was not released until after the bombing, so the Germans thought the islands were protected when they attacked. On the 2 July the incredibly popular Daily Mirror Cassandra column, known for its attacks on government, notes “Moreover, it was not until after the raids had started that they declared the islands to be an open area. Meantime thirty-nine [sic] people were mercilessly slaughtered.” [2]

Whatever the British had hoped to achieve by suppressing the information within 2 days of the bombing German troops had landed on the Channel Islands. Guernsey surrendered on the 30 June, followed by Jersey on the 1 July and Sark on the 4 July. It was the start of nearly 5 years occupation by the Germans.

The Manchester Guardian, Tuesday, 2 July 1940, p. 5. The Guardian (1821-2003) and The Observer (1791-2003), ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Accessed 8th May 2018.

“If we allowed ourselves to think and realise it all we could not go on”

This was an anxious and troubling time for Britain. Germany had quickly cut a swathe through Britain’s European allies and with the occupation of the Channel Islands could “now say that they occupy British soil”[3]. The Battle of Britain was just around the corner, there was a real fear that the Germans were on their way to the UK mainland and there was anger (and worry) over British people being “abandoned”.

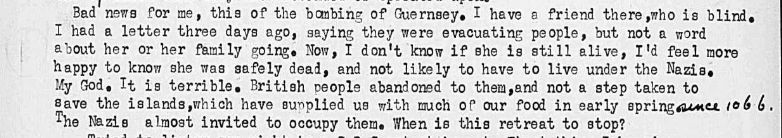

In the rural town of Steyning in West Sussex, Diarist 5399, a retired nurse, wrote of her concerns about the whereabouts of her friend from Guernsey and her anger at the islands being abandoned. From 30 June 1940 [4]:

Diarist 5399. [Diary]. July 1940. Mass Observation Online. Accessed 25th May 2018.

On 8 August she shares the sad news that the letter she sent her friend in Guernsey has been returned unopened. She is upset but “If we allowed ourselves to think and realise it all we could not go on”.

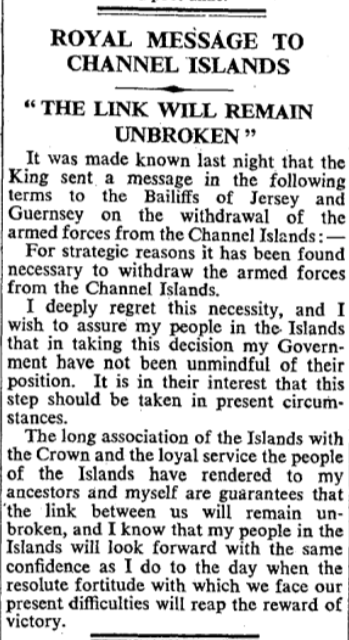

“The link between us will remain unbroken”

On the 9 July the newspapers reported on a message sent from King George VI to the Bailiffs of Jersey and Guernsey regarding the withdrawal of defences [5].

“Royal Message To Channel Islands.” Times, 9 July 1940, p. 2. The Times Digital Archive. Accessed 9th April 2018.

While “the link” may have been unbroken in spirit, in reality once the Germans occupied the Channel Islands communication channels with the UK mainland were cut off. Those with family or friends still living on the islands were unable to get any word from or to them.

It wasn’t until early November that a scheme was announced that would allow people to send short messages to and from the Channel Islands through the Red Cross. People were warned to “not expect a reply for some weeks.” [6], however, it appears that people had to wait a lot longer than this for replies and many never received replies at all.

In January 1941 in a letter to the editor of the Manchester Guardian [7], a Jersey soldier writes

“I have sent many messages through the Red Cross, and each time have been told to expect a reply “within weeks” – with, so far, no result…Surely it is not impossible for the Government to devise some means of communication – one aeroplane would be sufficient to convey all messages to relatives.”

The long years of occupation

Despite the large number of articles about the actual occupation in late June and early July 1940, relatively small numbers of news reports and articles appeared throughout the occupation, which perhaps goes to show how little contact there was with the islands during that time.

One person who kept the Channel Islands in the news was Lord Portsea (Bertram Godfray Falle, 1st Baron Portsea, of Portsmouth). From as early as July 1940 he was criticising “the Government’s policy in leaving the Channel Islands to the Germans” [8] and throughout the occupation he lobbied on their behalf regarding food and supplies [9, 10] and communications [11].

The Manchester Guardian, Thursday, 8 October 1942, p. 5. The Guardian (1821-2003) and The Observer (1791-2003), ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Accessed 7th May 2018.

News from the islands themselves did filter out from time to time. On 8 October 1942 The Manchester Guardian reports on a small Commando raid on Sark. The raid confirmed suspicions that Britons had been deported from the islands to forced labour camps on mainland Europe [12]. It was discovered later that over 2000 people from the Channel Islands had been deported at that time, and some had committed suicide rather than being sent away.

Over a year later it is reported that though rations (food and other supplies) are “skimpy”, they are pleased that the “health of the islanders had not suffered then as seriously as was feared”[13]. But they do note that this isn’t the case for everyone on the islands “Fortifications were built by Russians, Poles, and Czechs, who were described as in a terrible state of disease and malnutrition. They were treated brutally by the Germans”.

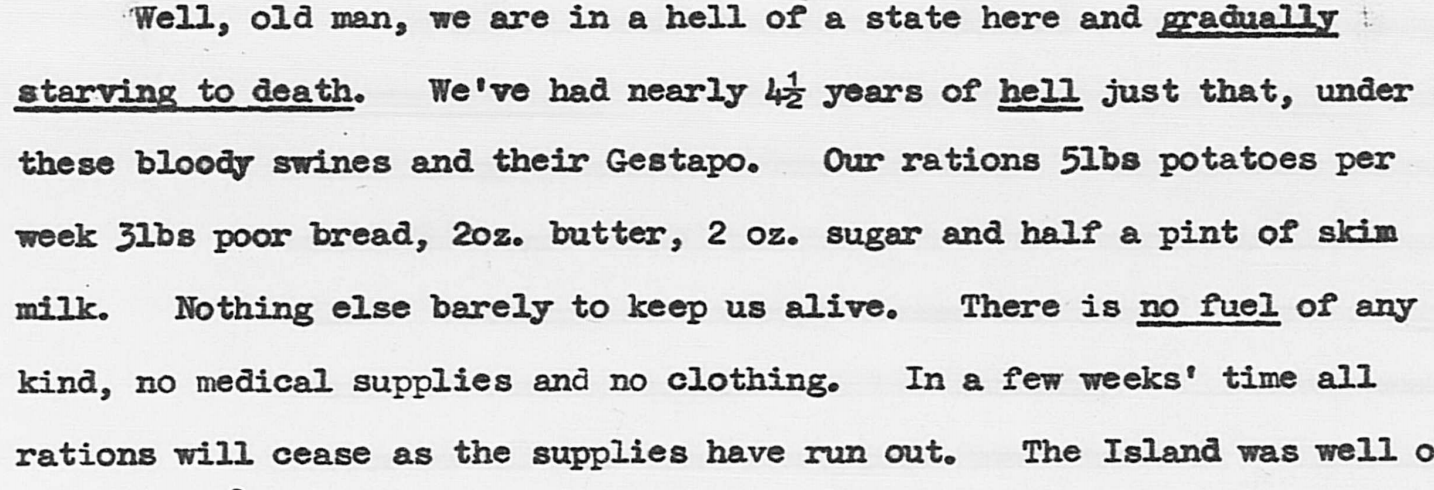

Letters from late 1944 paint a slightly different picture of life for the islanders. The Allies were now on the offensive and after D-Day (6 June 1944) had been pushing the Germans back through France and reclaiming territories. Unfortunately this had a negative impact on the Channel Islands as “Up to June 1944 the islanders were able to import supplies from France” [14] and now they were cut off. The situation for all of those living on the islands was beginning to become dire.

In an anonymised letter from Jersey on the 2 October 1944 [15] the writer states:

“We are dreading the cold weather, for we have no fuel, our ration being 1/2 cwt. of wet wood per month! No gas, and very little electricity. Food is scarce, and most rations come to an end in two or three weeks. The hospital will have to close its doors, as there will be nothing left by mid-November.”

One month later, on the 3 November, another anonymised letter writer is even more emphatic about the situation:

14. FO 898/222, Correspondence. 1944-45. MS Allied Propaganda in World War II and the Political Warfare Executive: Allied Propaganda in World War II: The Complete Record of the Political Warfare Executive (FO 898). The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). Archives Unbound. Accessed 9th April 2018.

These two letters give a real sense of what life was like on the islands at that time: the dwindling rations and supplies of any kind, the booming black market, financial hardship, distrust of the local authorities and their fellow islanders (with mentions of quislings, informers, spies and Jerry bags), the dread of the Germans coming knocking at their door, and their desperation to get help from the UK and to know they were not forgotten about.

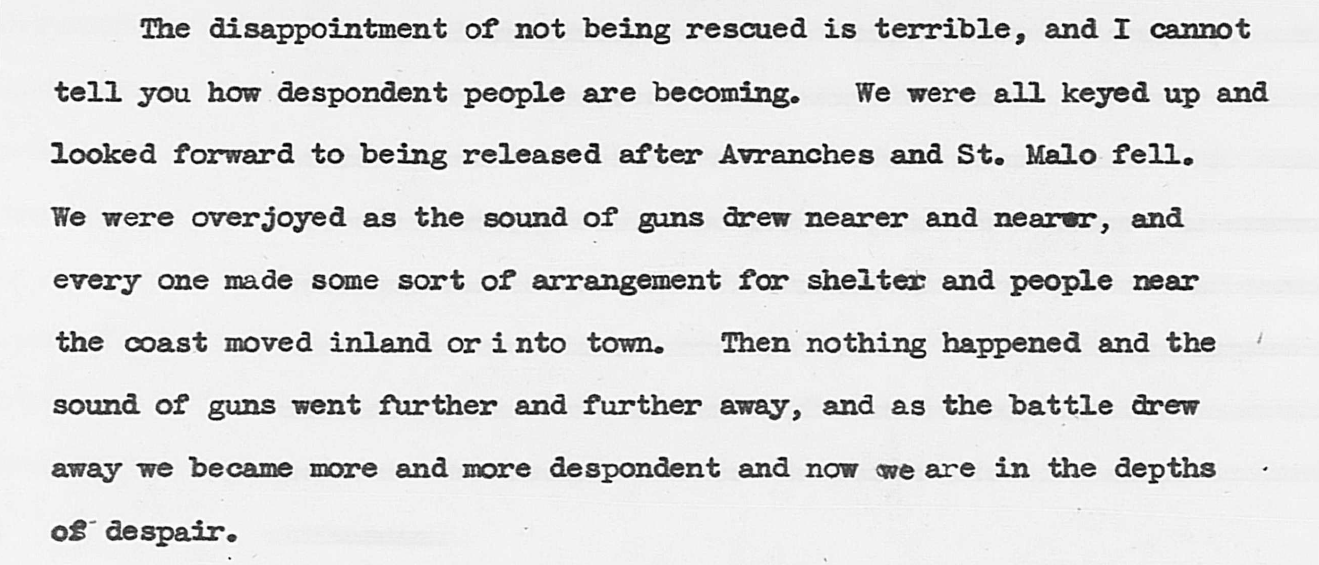

When the D-Day landings happened those in Jersey had heard the planes and the bombs. They knew what was happening and got excited as surely the Allies would be landing on their beaches soon to take back the islands. However, that was not the case and you can sense the heartbreaking disappointment in the letter from 2 October:

14. FO 898/222, Correspondence. 1944-45. MS Allied Propaganda in World War II and the Political Warfare Executive: Allied Propaganda in World War II: The Complete Record of the Political Warfare Executive (FO 898). The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). Archives Unbound. Accessed 9th April 2018.

“News from England”

The British used a wide range of propaganda during the Second World War, including posters, films, radio broadcasts, newspapers, etc. One such method was dropping leaflets from aeroplanes over enemy occupied territories and, you can see an example of one such leaflet dropped over the Channel Islands in the early months of the occupation in picture below.

Series 3: Air Dropped Periodicals, Channel Islands: News From England ( For The Channel Islands). 30 Sept. 1940. MS Psychological Warfare and Propaganda in World War II: Propaganda, Air Dropped and Shelled Leaflets and Periodicals. McMaster University Library. Archives Unbound. Accessed 9th April 2018.

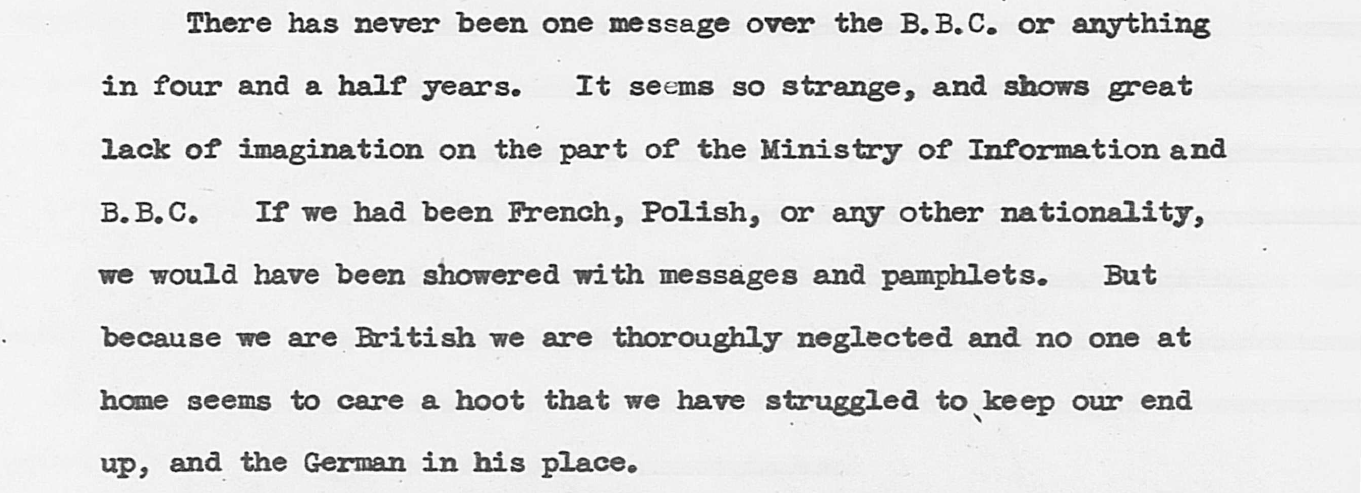

However, leaflet drops over the Channel Islands were few and far between and it seems no other form of propaganda, or very little, from the British was aimed at them. As a secret report on the Channel Islands in late 1944 [16] states:

“During the years of enemy occupation the Channel Islands have received only slight attention from Great Britain. With the exception of a very occasional leaflet during the early stages of occupation, no attempt has been made to keep in touch with the islanders. They are rarely mentioned in the press or on the radio. The subject of the Channel Islands seldom crops up in the House, and when it does the Channel Islanders are unaware of the fact. They are acutely conscious of this and feel hurt at being ignored by the British information and propaganda service.”

In the anonymised letter from October 1944, which is actually included in the aforementioned report, the writer is at once scathing and hurt about this lack of propaganda and communication from the “motherland”.

14. FO 898/222, Correspondence. 1944-45. MS Allied Propaganda in World War II and the Political Warfare Executive: Allied Propaganda in World War II: The Complete Record of the Political Warfare Executive (FO 898). The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). Archives Unbound. Accessed 9th April 2018.

Why the Channel Islands were ignored in this respect I’m not really sure? Strategically they were not as important as other occupied territories but they were “British territory” and “British citizens” so it seems odd that they were overlooked. One simple explanation, though not the only one, may be that these leaflets (or news sheets as they are often referred to) by November 1940 were not being produced at the rate that was intended and “In view of the fact that the Channel Islanders apparently are still able to listen freely to the B.B.C. the question arises whether it would not be better to abandon the Cahnnel [sic] Islands’ News Sheet altogether and concentrate on France.” [17]

Unfortunately in June 1942 the Germans decreed that all wirelesses on the islands must be handed in, cutting off the islanders even more from Britain. But even before that it appears there was very little mention of or news directed at the islands.

News and rumours did get through from time to time though, despite drastic consequences if discovered a number of islanders hid their radios rather then hand them in and others were able to build crystal sets. Both letters from late 1944 make mention of comments in the House of Commons recently where it’s rumoured it was said that the islanders were doing well and were well looked after. The anonymous letter writer from November 1944 [18] is outraged,

“By Christ I’d like to get hold of that lying bastard and ram his lies down his throat.”

“Let ’em starve…They can rot at their leisure”

The situation in the Channel Islands really was grim by late 1944 and it was finally agreed that the Red Cross could send a relief ship to the islands with Red Cross parcels for the islanders as well as medical supplies, soap, etc.

© Mark Cairney

It had taken several months of negotiations for this to happen. Infamously during these discussions Churchill had scribbled “Let ’em starve. No fighting. They can rot at their leisure” on the end of the minutes of a Cabinet meeting on 27 September 1944 [19]. It’s presumed he was talking about the Germans and not the islanders themselves (there was a concern that any relief sent to the islands would be intercepted by the Germans and not passed to the islanders) but they were all starving.

The Daily Mirror reports on the 23 December 1944 that the SS Vega was on its way to the Channel Islands and was carrying “300,000 food parcels, packed in Canada, 100,000 special necessities for invalids, two tons of medical supplies, four tons of soap and five tons of salt.”[20] By the 1 January 1945 newspapers are reporting that the relief ship had arrived at the Channel Islands, stopping first at Guernsey on the 27 December 1944[21]. The Germans did not interfere with the supplies, in fact they helped unload the boats, and these went directly to the islanders.

Speaking after the occupation one islander commented “The Red Cross parcels which came in that January just did the trick. We should have been finished without them. But everybody stuck it.” [22]

” Our dear Channel Islands are also to be freed today”

By early 1945 the end of the war in Europe was in sight. The Allies were continually making gains, Mussolini was killed on 28 April and Hitler committed suicide on 30 April. The 8 May 1945 was ‘Victory in Europe’ (VE) Day, and it marked the formal end of the war in Europe. In a speech on the 8 May Churchill mentioned that “our dear Channel Islands are also to be freed today.” [23]

The Channel Islands had to wait until the next day, 9 May, before they were actually liberated, when the Germans signed an unconditional surrender on the British destroyer, Bulldog, off the coast of Guernsey.

Willis, Douglas, and Home Service. “The Bulldog Takes the Surrender.” The Listener, 17 May 1945, p. 539. The Listener Historical Archive, 1929-1991. Accessed 22nd June 2018.

In a Universal Newsreel from 1945, available from Academic Video Online, you can see footage (starts around the 04:40 mark) of the signing of the unconditional surrender, the Union Jack flying on the islands once again, Germans surrendering masses of equipment and senior commanders being taken away as prisoners of war, as well as joyful scenes of the islanders celebrating. An article in The Manchester Guardian [24] describes the scenes on the islands on the night of the 9th May:

“To-night, as we are leaving for England, Channel Islanders are cheering from motor-boats and rowing craft and overhead Allied aircraft are zooming and sweeping, firing coloured lights, which drop green, red and violet over the freed and joyous Channel Islands.”

Discover more about the occupation of the Channel Islands

I’ve really only touched the surface of the occupation in this post and there is so much more that could be looked at or stories to be told. If you are interested in finding out more about the occupation of the Channel Islands then why not search DiscoverEd to find what has been written on this subject already? Or you could use Box of Broadcasts (BoB) to find documentaries, films, tv shows, etc., about the occupation. Here are just a few suggestions:

- Time Team: Hitler’s Island Fortress – Tony Robinson and the team investigate a German anti-aircraft battery built during the Nazis’ five-year occupation of Jersey.

- Coast: Invaders of the Isles 1 – Nick Crane is on Guernsey and explores a German bunker that has been sealed since the end of the Second World War and also hears very different stories of the Nazi occupation from two survivors.

- Walking through History: Nazi Occupation – Channel Islands – Tony Robinson’s four day walk through Guernsey and Jersey explores their unique wartime heritage.

- Nazi Megastructures: Hitler’s Island Megafortress – documentary that looks at how German occupying forces fortified the Channel Islands, using interconnected bunkers, gun emplacements, observation towers, strong points and tunnels that could withstand attack from the sea or air.

- And finally, last but by no means least, The Channel Islands at War, a 3-part documentary series presented by Bergerac himself John Nettles. Watch Invasion and Occupation, Collaboration and Resistance and Liberation and Reconstruction.

If you’re ever in Jersey I would definitely recommend the Jersey War Tunnels. It brings the story of the occupation to life and allows you to find out so much about the lives of the islanders during this time; the building of the tunnels; the absolutely horrendous conditions and treatment of the forced workers, including prisoners of war and political prisoners, provided by the Organisation Todt (OT) to take part in the massive construction work on the island and more. (And I must point out there are other Second World War museums, exhibitions and heritage sites on the Channel Islands, it’s just I haven’t had a chance to visit them yet!)

Online primary sources used

I did fairly brief searches of the various different databases but it shows how much you can find with just some simple searches.

- Academic Video Online

- Archives Unbound

- Box of Broadcasts (BoB)

- Gale Primary Sources (which searched The Times Digital Archive, British Library Newspapers and other databases)

- The Guardian (1821-2003) and The Observer (1791-2003), ProQuest Historical Newspapers

- House of Commons and House of Lords Parliamentary Papers (UK Parliamentary Papers), ProQuest.

- Mass Observation Online

- The Scotsman (1817-1950), ProQuest Historical Newspapers

- UK Press Online

All the online archives mentioned above can be accessed via the Databases A-Z list or Databases by Subject pages.

Access is only available to current students and staff at University of Edinburgh.

Note that BoB is only available on the UK mainland (using VPN may help you get round this). And you will normally be asked to provide your University email address the first time you log in to BoB.

Caroline Stirling – Academic Support Librarian for History, Classics and Archaeology

Notes

- Taken from CAB 65 Second World War conclusions from The National Archives Cabinet Papers. Particular quotes come from War Cabinet 172 (40), June 19, 1940 at 12.30pm, p. 520. Accessed 7th May 2018.

- “The Armed Guard,” The Daily Mirror, July 2, 1940, p. 4. UK Press Online. Accessed 1st June 2018.

- J. de G. Gaudin, “Occupation of Channel Islands,” The Scotsman, July 3, 1940, p.9. The Scotsman (1817-1950), ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Accessed 8th May 2018.

- Diarist 5399. [Diary]. At: Place: University of Sussex. Mass Observation Online. Accessed 25th May 2018.

- “Royal Message to Channel Islands,” The Times, July 9, 1940, p. 2. The Times Digital Archive. Accessed 9th April 2018.

- “Messages for Channel Islands,” Evening Telegraph, November 4, 1940, p. 1. British Library Newspapers. Accessed 9th April 2018.

- “The Channel Islands,” The Manchester Guardian, January 16, 1941, p. 8. The Guardian (1821-2003) and The Observer (1791-2003), ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Accessed 8th May 2018.

- “Evacuation of Channel Islands Criticised,” Aberdeen Journal, July 10, 1940, p. 6. British Library Newspapers. Accessed 9th April 2018.

- “Lords Sitting of Wednesday, 3rd December, 1941,” 121 (1941): House of Lords Hansard, 1941-42. Regnal Year: George VI Year 5. Debates, Fifth Series, Volume 121, Columns: 157-196. UK Parliamentary Papers. Accessed 27th April 2018.

- Lord Portsea. “Record Of Parliamentary Motion And Debate About Food Situation In Jersey And Guernsey. Part 4. Co-Ordination. General. Food Situation In Occupied Europe,” FO 371/36511-0006, March 18, 1943. Conditions & Politics in Occupied Western Europe, 1940-1945 (Archives Unbound). Accessed 9th April 2018.

- “Lords Sitting of Tuesday, 28th January, 1941,” 118 (1941): House of Lords Hansard, 1940-41. Regnal Year: George VI Year 5. Debates, Fifth Series, Volume 118, Columns: 236-258. UK Parliamentary Papers. Accessed 27th April 2018.

- “Channel Island Deportations,” The Manchester Guardian, October 8, 1942, p. 5. The Guardian (1821-2003) and The Observer (1791-2003), ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Accessed 8th May 2018.

- Our London Staff, “Life in Channel Islands,” The Manchester Guardian, December 6, 1943, p. 5. The Guardian (1821-2003) and The Observer (1791-2003), ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Accessed 8th May 2018.

- “FO 898/222, Correspondence,” 1944-45, p14. Allied Propaganda in World War II and the Political Warfare Executive (Archives Unbound). Accessed 9th April 2018.

- “FO 898/222, Correspondence,” p. 20.

- “FO 898/222, Correspondence,” p. 15.

- “FO 898/9, Meetings At Country HQ And Ministerial Correspondence On So1 And So2 Weekly Progress Reports For 1941,” 1940-41, p. 280. Allied Propaganda in World War II and the Political Warfare Executive (Archives Unbound). Accessed 8th May 2018.

- “FO 898/222, Correspondence,” p. 17.

- Maev Kennedy, “Light shines on Jersey’s wartime tunnels,” The Guardian, May 4, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/may/04/secondworldwar.world. Accessed 4th June 2018.

- “£200,000 Relief Ship On The Way,” The Daily Mirror, December 23, 1944, p. 4. UK Press Online. Accessed 4th June 2018.

- “Relief Supplies Arrive”, Nottingham Evening Post, January 1, 1945, p. 1. British Library Newspapers. Accessed 4th June 2018.

- “Channel Islands,” Western Gazette, August 17, 1945, p. 6. British Library Newspapers, Accessed 9th April 2018.

- “Unconditional surrender,” Listener, May 10, 1945, p. 508. The Listener Historical Archive. Accessed 22nd June 2018.

You can also listen to the speech online via the Internet Archive. - “Channel Islanders’ Cheers And Tears,” The Manchester Guardian, May 11, 1945, p. 6. The Guardian (1821-2003) and The Observer (1791-2003), ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Accessed 8th May 2018.

Pingback: On trial: Prosecuting the Holocaust: British investigations into Nazi war crimes | HCA Librarian

Pingback: Normandy landings: through our digital primary sources | HCA Librarian