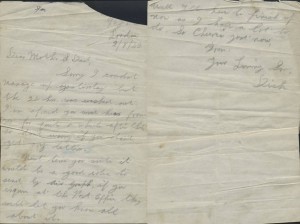

All of history seems to be contained in the letters of ordinary people living in extraordinary times. We may know what backdrop will emerge, but there are seldom enough traces to discover the fate of the individual. The following letter, sent by a Dr Friedrich M Urban of Brünn a short while after the Nuremberg rally of 1938 to Professor Godfrey Thomson, is a fascinating example:

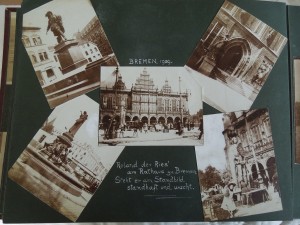

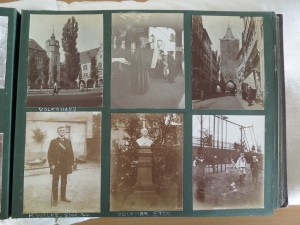

It is not clear from Thomson’s papers how he knew Urban – quite possibly he had met him while studying in Strasburg, during which time he undertook a tour of Europe.

Urban’s letter shows a great deal of affection for Thomson and his wife, referring to the kindness of the Thomsons to their girls. Speaking to Thomson as an old friend, Urban thanks him for the suggestion of medicinal honey to help with his gallbladder, and reports on the method’s success! But the mood in the letter quickly turns:

Much has happened since we met and took those pleasant walks in the parc [sic] of the Spielberg. Our country was involved in a catastrophe which is bound to have the most serious consequences for its citizens. The old conditions cannot continue and some new form of political and economic existence must be found.

The first consequence was that we had to separate from our children. When we listened to Hitler’s speech at Nurenberg [sic] – for who did not? – we understood that he contemplated violent measures against our country. We wished to have the girls out of the way and asked Mr and Mrs Sanderson and Dr Fernberger for hospitality for our children. We got positive answers at once and managed to get the girls across the German frontiers. It was in the nick of time, for three weeks later the frontiers were closed.

There is much about the letter that is perplexing – initially, I thought Urban might have been writing from Brunn in Austria, but for the addition of the umlaut (both Germany and Austria have regions called Spielberg to confuse matters further). He could also have been writing from Brno in the Czech Republic, which does not seem an unlikely option considering Brno is home to Spielberg castle and was captured by Germany in 1939. However, it does seem rather unlikely that Urban would use the German spelling of his town in that instance.

If we are to assume that Urban is writing from Germany, his phrase ‘our country was involved in a catastrophe’ is an interesting one. The ‘catastrophe’ he refers to is likely the annexation of Austria by Germany, which took place earlier in the year. It was a catastrophe caused by Germany’s actions rather than their involvement, but he makes a clear distinction between the activities of the Nazis in this instance and ‘our’ country, his country, refusing to identify one with the other.

Urban tells how the girls stayed in London with the Sandersons for a few weeks, before sailing to New York where they remained in the custody of the Fernbergers in Philadelphia. He mentions how they are waiting for a letter describing the girls’ travels, but can’t hide quite how much they are missed:

We miss the girls tremendously, but inspite [sic] of this we thank God every day that they are not here and that we have friends who look after them.

He talks about how life at Brunn will likely become ‘rather difficult’, and asks for Thomson’s help in finding teaching work in Britain. While he accepts that this may be impossible, and admits his chances of securing work in Britain are ‘very small’, Urban remains optimistic nonetheless – thankful even – that his daughters are safe, and his health good. I can find no trace of Urban – whether he and his wife were ever reunited with their daughters remains a mystery. For me, this serves to make the letter, which describes the plight of millions throughout Europe from the perspective of one individual to another, all the more touching.

If you have any information regarding Dr Urban, do please comment.