In 1932 and 1947, every 11 year old child in Scotland was given an intelligence test, known as the ‘Moray House Test’, as part of the Scottish Mental Survey. Additionally, they were the subject of a questionnaire which gleaned information about their social and familial background. All of this was in response to the idea that as a nation, Scotland’s intelligence was decreasing due to a supposed differential birth rate. The resulting data, which proved this hypothesis wrong, survives to this day. It is an entirely unique and rich source of information, which has allowed current researchers at the department of Psychology at the University of Edinburgh to undertake pioneering research exploring cognitive ageing.

The creator of these tests (and chairman of the second Scottish Mental Survey) was none other than Professor Sir Godfrey Hilton Thomson.

So just who was Thomson- and why do we think him so important?!

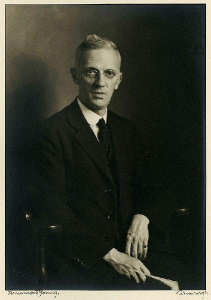

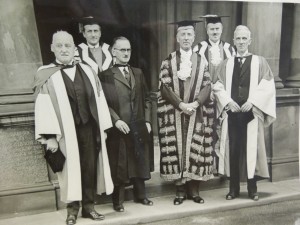

Thomson was a pioneer in the interloping fields of intelligence, statistics, and education. He was the first person to the Bell Chair of Education at the University of Edinburgh, and the Directorship of Moray House School of Education simultaneously; published prolifically on the topic of psychometrics; debated voraciously with eminent statistician Charles Spearman for almost 30 years, and last, but by no means least, was a Knight of the Realm thanks to his considerable services to Education. More than this, Thomson was an egalitarian from a humble background, a ‘lad o’ pairts’ who achieved greatness thanks to his talent and determination, and who believed deeply in equality and fairness.

Godfrey Thomson, c1920s

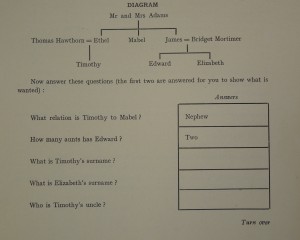

The ‘Moray House Tests’ which the children sat in 1932 and 1947 actually had their origins in Newcastle in 1921. The local authorities, who at that time provided bursaries for secondary school education, were concerned by a lack of applicants from rural backgrounds. Thomson was conscious of the fact that rural children were often absent from school, so he wanted to create a test which would allow children to demonstrate ‘native wit’ or innate intelligence, rather than a test which would rely upon past learning.

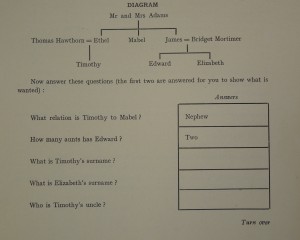

Example of a question from the Newcastle tests

This striving for equality was typical of Thomson, and perhaps in part a result of his own humble background. Born in Carlisle in 1881, his Mother left his Father, taking the infant Thomson with her, to return to her childhood home in Tyneside. His Mother and he lived with her three sisters, and she earned a very modest income from working with a sewing machine firm in Newcastle.

Thomson had plans to become a ‘pattern maker’, a specialist joiner who made wooden models of steel castings for engineering works, after leaving High Felling Board School. However, after sitting a scholarship examination, Thomson found himself at Rutherford College, where he discovered various interests in mathematics, music, and etymology. Rutherford College was supported largely by the students entering and winning examinations as part of a government scheme, and Thomson soon became a veteran in these examinations, obtaining prizes for English and Mathematics amongst others.

Thomson as a young boy

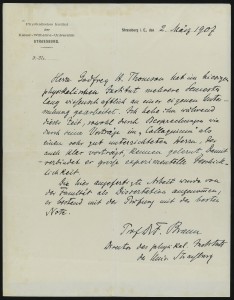

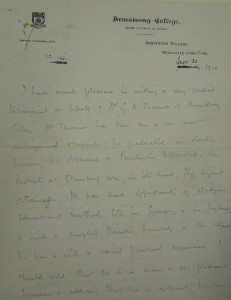

At 16, he sat the London Matriculation exam, and returned to High Felling Board School as a pupil teacher. During this time, he took additional evening classes, studying chemistry, physics, botany, and zoology. In 1889, aged 18, Thomson sat the Queen’s Scholarship, an all-England competition, and came third, continuing his studies in what would become Armstrong College, and later King’s College, at Durham University. Thomson studied for his teaching diploma and a joint Mathematics and Physics degree simultaneously, and graduated with distinction. He went on to study at Strasbourg under the Nobel prize winning physicist, Professor Ferdinand Braun, and graduating Summa cum Laude following his work on Herzian waves.

After his three years in Strasbourg came to a close, Thomson returned to Newcastle, attaining the post of assistant lecturer at Armstrong College in order to fulfil the obligation of his scholarship. It was here he met his wife, Jennie Hutchinson, a fellow lecturer, and here he gained an interest in Educational Psychology. In 1916 he published a paper which would ignite a 30 year debate with the eminent statistician, Charles Spearman.

Essentially, the debate centred around Spearman’s Theory of Two Factors regarding intelligence. He believed that performance in each subject was down to specific abilities linked to each, and general ability linked to all. Thomson provided an alternative for this in his bonds model, in which he hypothesised that any mental task requires a number of ‘bonds’, some of which are more closely related to others in ‘pools’ (Thomson made a link between these bonds and the neurons of the brain). Thomson had no wish to discredit Spearman’s theory, rather to show that his provided an alternative, and he showed good sportsmanship in holding off publication during the war years to enable Spearman, who was serving, time to respond. However, the debate would continue until Spearman’s death in 1945.

In 1925, Thomson accepted his position in Edinburgh and his family (by now including his son, Hector) moved to Edinburgh. It was here in what became the Godfrey Thomson Unit that Thomson and his team would formulate the Moray House Test. The test, which included questions on verbal reasoning, English, and mathematics, was also used by local authorities throughout the UK for School selection. Thomson was not wholly comfortable with this, but concluded testing was preferable to nepotism, and worked on making the tests as fair as possible. Thomson could have made a considerable fortune on the tests, but instead insured all royalties were transferred into a research fund to facilitate their continual improvement.

On his retirement in 1951, Thomson, who had proved highly popular amongst staff and students, was presented with 2 portraits of himself by RH Westwater, one of which hangs in Moray House to this day. He passed away in 1955.

These are just some of the many reasons why we think Thomson is incredibly important, and has been unfairly neglected from the history of psychometrics. This neglect is, in part, due to scholars having no primary material to consult – the archive itself was only discovered in 2008, and it is no exaggeration to say it was rescued.

It is our task to catalogue his papers, and to ensure he finally receives the recognition his work deserves. In the coming months, we will be blogging about Thomson, his collection, and the people he came into contact with throughout his life and career. We hope you will enjoy!