(Coll-1310/1/2/2 Family Photographs)

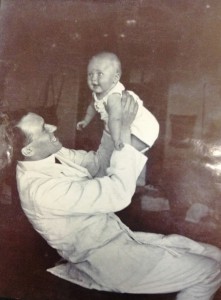

With father’s day coming up this weekend, I thought it would be interesting to blog about the father/son relationship between Godfrey and Hector Thomson. When Hector was born in 1917, it was clear that Godfrey had a new test-subject in his infant son!

Immediately after Hector was born, Thomson began to keep a journal recording his son’s development from his birth until the age of ten (ref: Coll-1310/1/7), a copy of which is among the records of the Godfrey Thomson collection. This journal is fascinating in its level of observation and detail about young Hector, and shows the depth of Godfrey’s commitment to understanding childrens development and intelligence. Who knows what Hector thought about the in-depth analysis of his behaviour and speech throughout his childhood, but the entries give a great insight into what it must have been like in the Thomson household.

(Coll-1310/1/7 Papers Regarding Hectors Development)

(Coll-1310/1/7 Papers Regarding Hectors Development)

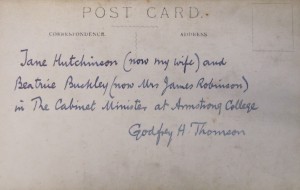

The many photographs in the Thomson family albums illuminate the family further, and contain several charming pictures of Hector and Godfrey together.

The first entry records Hectors appearance as a new-born on the 18th of February 1917. Godfrey notes that he “has blue eyes, brown hair, long thin limbs and a large triangle head”! Less than a month later, it is recorded that “he looks at bright objects and turns his head about when a noise is made. Finds bright objects better than he finds noises however. Smiled twice today. His eyes are much darker than when he was born and perhaps they are changing from blue to brown.”

Frequent diary entries contain details about Hector’s early years, including his thumb-sucking, his ability to see his mother in the mirror, picking up items, first words, illnesses and learning to walk. As the years went by, quotes from the rather amusing Hector were also recorded in the journal, as well as stories he made up, dreams he recounted for his parents and several drawings. Despite early attempts by his parents to make him write with his right hand, his natural tendency to left handedness won out in the end! Interestingly he had a propensity to write in mirror image, which is shown in some of his drawings.

Godfrey was obviously very interested in Hector’s intellectual development and the scientific conclusions he could draw from his observations; but this file is also a testament of the affection, pride and amusement he felt while watching his son growing up.

Earlier blog entries have told about Hector as an adult, his wide ranging travels and his marriage to Andromache. Rather touchingly, even as an adult he always referred to Godfrey as “Daddy”. He followed in his father’s footsteps into the field of education to become a popular and well respected teacher in Nicosia and later at the University of Aberdeen.

Neasa Roughan, Godfrey Thomson Project Intern