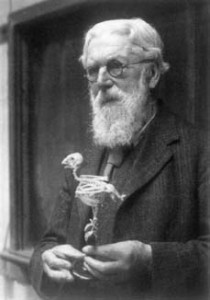

Thomson described education as ‘the food of the Gods’, but he might well have described friendship in the same way. The many letters of grief sent to Lady Thomson following his death attest to how he cultivated and valued friendship throughout his life. But of all the friendships present in his papers, the one which I have found the most touching is that between himself and the delightfully named Sir James Fitzjames Duff, who was knighted on the same day as Thomson.

Thomson and Duff after being Knighted – Duff is situated on the right hand side behind Thomson, 1949

An eternal bachelor who had his widowed Mother, and later his equally wonderfully named unmarried sister, Hester, live with him throughout his adult years; who refused to learn to drive; and who was gloriously and unapologetically dreadful at golf, Duff sounds like he might just have had all the ingredients of the quintessential British eccentric!

Duff’s friendship with Thomson spanned from his employment at Armstrong College in 1922, when Thomson gave him a job as lecturer. Duff continued to work in Durham University, having been promoted to Warden of the Durham colleges in 1937, until his early retirement in 1960, as well as the various educational commissions and Committees he devoted his time to. He was enthusiastic about his career throughout his life, and very much enjoyed his work at Durham. In a letter to Thomson upon hearing the sad news of his illness, Duff writes:

Its just upon 33 years since you chose me for the vacant lectureship at Armstrong College; and I regard that as about the most fortunate day of my life, partly because it shaped my career in a way that has given me great happiness and more than adequate success, but partly because it led to my friendship with you. Considering that I was only on your staff for a very short time, its surprising how close and, to me at least, delightful the friendship has been. Part of that joy has been that I always looked up to you, as a younger man to a wise and kind elder. And at my age there are few indeed left to whom I can look up in that way. So don’t leave us yet, if you can help it. And if you can’t help it, let me tell you while I can that so long as I live, my admiration and affection for you, and my gratitude for your friendship, will not die. [Coll-1310/1/1/25]

Duff was not short of friends – he was renowned for his conversational skills, and could hold an audience rapt with his stories. One might say he seemed an odd companion for the more quiet, considered, Godfrey, but the two quickly became friends. They worked together on pioneering intelligence test work in Northumberland during which time Duff was seconded to Northumberland county council as educational superintendent. In particular, they were trying to ensure that clever children who suffered from a lack of education due to living in rural areas, would not miss out on secondary school places. Several items of correspondence survive from this time in the Duff papers held in Durham University.

From an affluent background, Duff had had many of the advantages Thomson had lacked, attending the prestigious Winchester College, then Cambridge. Duff much admired Thomson’s achievements in light of his relatively humble background:

Godfrey’s was really was a wonderful life. Personal affection apart, I can think of nobody whose whole life was so filled with happy beneficent actions as his. And the triumph over the handicaps and poverty of his boyhood adds a special sort of lustre to it all. [Coll-1310/1/1/25]

It was Duff who would write Thomson’s obituary, though the copy in the collection with Lady Thomson’s annotations attests that she thought his accounts of Thomson’s impoverished background greatly exaggerated, and gave him a jolly good telling off!

Following Thomson’s death in 1955, Duff kept in touch with Hector, and later edited Thomson’s autobiography, Education of an Englishman, ensuring its publication in 1969 much to the delight of Hector. Many items of correspondence survive between himself and Hector, which exchange anecdotes of Thomson many years after his death. Lady Thomson features as a topic rather than a correspondent, since by this time she was suffering from ill health herself, and spent a great deal of time in hospital. Rather touchingly, Hector tells Duff of his Mother’s removal to hospital, and her insistence, in her confused state, that the drive would have to be swept and cleaned because ‘Mr Duff’ was coming. Throughout this period, Duff continues to write to Lady Thomson, addressing her as ‘My dear Jennie’.

Upon his sudden death at Dublin airport in 1970, his beloved sister, Hester, writes to Hector Thomson, expressing her gladness that Duff managed to finish editing Thomson’s biography and telling Hector about the manner of his death:

As for the manner of James’ going, I do not think he would have wished it otherwise. he had a slight heart attack while on holiday in Ireland, made an excellent recovery, and was passed fit to go home, then collapsed and died quite suddenly (of a coronary thrombosis) at Dublin Airport. Although I miss him more than I can say, I could not wish him a long illness and old decline.[Coll-1310/1/1/28]

Fifteen years after Thomson’s death, Hester tells Hector that he still has Thomson’s photograph on his mantelpeice:

There is a photograph of your Father on James’ study mantelpiece…He is standing with his hands on a desk, wearing glasses, aged perhaps 40. [Coll-1310/1/1/28].

It is clear that Thomson’s friendship meant a great deal to Duff – in a letter to Lady Thomson following his death, he writes, ‘I am a better man for loving him, and having had his friendship’. But equally, it is clear his friendship too meant a great deal to Thomson, and indeed the Thomson family. True to his word, Duff’s admiration and affection for Thomson did not die.

* Any stories of friendship (or romance!) from your historical research? Tweet me about it at @emmaeanthony using the #makehistoryhuman!

(Coll-1310/1/7 Papers Regarding Hectors Development)

(Coll-1310/1/7 Papers Regarding Hectors Development)