In his mid 20s, Thomson found himself studying for a PhD under the formidable talents of Nobel Prize winining physicist, Karl Ferdinand Braun, at the University of Strasburg. Today’s object is from this period, and likely held a great deal of sentimental value to Thomson:

The watch fob bears the initials of Thomson’s student ‘verein’ or club, the M.N.St.V, (the mathematical and natural science student verein), which he described as a humble version of the expensive ‘Burschenschaften’, elite student clubs which exist to this day and often involve duals (or Mensur):

In the Mensur…the fighters are protected by goggles and nose-piece, by mattress-like chest and arm protection, must not move or flinch, hold the straight pointed rapiers above the head, touching and at the word…strike at each other’s head and faces. Two seconds crouch with drawn swords and at the first touch they strike up the combatant’s swords. this is repeated until the referee gives a decision, or for a given number of rounds. Often one man gets all the cuts, and the other none. they are mostly on the head, but also on the forehead and cheek and chin, a ‘Durch-zieher’ cutting across both cheeks almost horizontally. Then senior medical students give hasty and not very sterile assistance and stitchings, and the heroes drink beer and swagger (if well enough) through the next few days.

The Education of an Englishman, p.53

The scarring resulting from the dual was, and is, seen as a badge of honour, and students often deliberately irritated the wound, packing it to ensure it was widened. In Thomson’s humbler club, duals were rare and usually in response to an insult or wrong doing. No uniforms were required, but members wore a watch fob with the verein’s arms. Thomson’s Leibbursch*, Carl Andriessen (whose name is engraved on the watch fob with Thomson’s) gave him his.

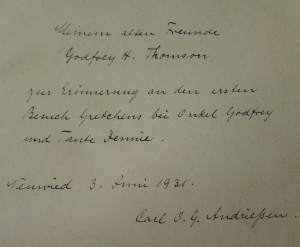

After World War I, Thomson lost contact with many of his German friends, many of whom were killed or missing. However, the inscription of one book in his collection, Das Deutschland Buch, shows he kept in touch with Andriessen:

The book is inscribed with a message to Thomson and his wife Jennie, thanking them for their hospitality, and dated June 1931 – 25 years after Thomson left Strasburg. The more fluent among you might notice he refers to them as ‘Aunt’ and ‘Uncle’, which made me wonder if the giver was in fact Andriessen’s son, though he refers to them as old friends, which would suggest otherwise. It contains many beautiful images of Germany, a country Thomson loved his whole life, despite the ravages of two World Wars:

I found the book rather touching – despite the remaining animosity of their prospective nations after World War I, the two clearly have a strong friendship, and Andriessen is able to give Thomson a book about the beauty of his own country, a country Thomson also loved.

For Thomson, the time he spent in Strasburg was one of the happiest periods of his life. It allowed him to indulge in his passion for research, undertaking intensive work on Herzian waves. His German became fluent, and he immersed himself in German culture. The watch fob, which he treasured for all those years, perhaps served as the perfect reminder of his life there, and a reminder of enduring friendship.

*’A second year student who adopts a freshman, shows him the ropes, and can claim services in return’

With many thanks to Sarah Noble, LHSA Conservation Intern, who patiently spent a morning showing me how to make bespoke museum boxes and made the lovely box for Thomson’s watch fob!