As mentioned previously, Thomson’s collection features a great many interesting letters, and I’ll be sharing these throughout the course of the project. One which I found particularly touching was a letter from Thomson’s friend, Marjorie Rackstraw (1888-1981), to Lady Thomson shortly after Thomson’s death.

Rackstraw is an excellent example of the interesting people drawn to the Thomsons. One of a five-daughter family, with no brothers, Rackstraw’s Father encouraged all of his daughters educationally, and gave them a small proportion of his fortune to afford them independence. Her collection features slides, photographs, and several letters – many of these are rather charmingly addressed to ‘Dear old Rack’!

The Thomsons met Rackstraw at Edinburgh University, where she was warden of Mason Hall from 1924 to 1937. Before then, Rackstraw had studied history at Birmingham, found herself at Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania, and worked as a relief worker in Russia during the famine.

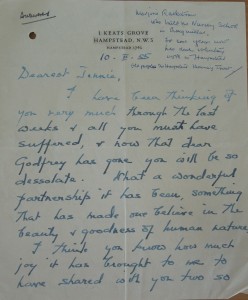

As Lady Thomson’s annotations on the letter [below] suggest, Rackstraw’s particular concern was for the care of the elderly – particularly the poor, and she was Chair of the the Hampstead Old People’s Housing Trust until she was 80. She was a firm socialist throughout her life, a member of the Fabian society, and a Labour councillor. Her aid work did not end in Russia, she also volunteered for with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration throughout World War II. Rackstraw had suffered from spinal difficulties as a result of contracting polio as a child, which impaired her movement somewhat, but she refused to allow this to get in the way of her humanitarian work, or indeed any other aspect of her life.

Readers might remember my earlier blog about the partnership of Thomson and Lady Thomson, and Rackstraw’s letter gives us more insight into this:

What a wonderful partnership it has been, something that has made one believe in the beauty and goodness of human nature.

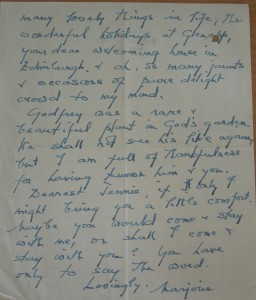

I think you know how much joy it has brought me to have shared with you two so many wonderful things in life, the wonderful holidays at Glenapp, your dear house in Edinburgh, and oh so many jaunts

The Thomson’s had a great many friends who frequented their house, and Thomson himself often chose to work from home, so its unsurprising Marjorie comments on the warmth of his home. Most touchingly, she calls Thomson ‘a rare plant in God’s garden’.

Many of the letters sent to Lady Thomson laud Thomson’s achievements and his intellect, but Marjorie’s letter simply remembers the man. Her warmth and her kindness are evident, as are the love and esteem she felt for the family.

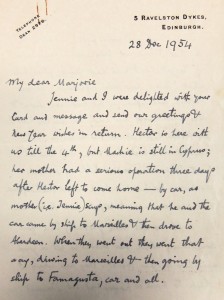

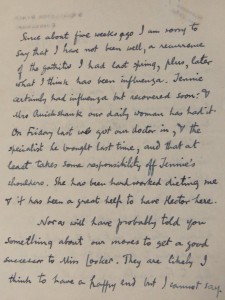

Within Marjorie’s collection, we also have a letter from Thomson, sent a few short months before he died, which further shows the intimacy and friendship between the two:

As the letters of condolence sent to Lady Thomson show, his death was a surprise to many, since Thomson, perhaps unsurprisingly for his generation, did not mention his health troubles to his friends and acquaintances. However, he does share them with Rackstraw, telling her her that a specialist visited him, and hinting at how he is struggling to be cheerful.

Unbeknown to Rackstraw, Thomson’s ‘tummy troubles’ were down to cancer, and he would pass away a few months later in February 1955. It is likely Thomson and his family were unaware of this too – particularly since his son Hector, as Thomson mentions in the letter, had taken to shouting ‘Goodbye, Daddy, don’t die till I come back!!’!

Collections like Thomson’s and Rackstraw are fascinating not only because they tell us something of the creators’ work, but because they offer the researcher a slice of 20th century life, and an example of the colourful personalities, networks, and friendships abounding – Thomson’s collection informs the user of his work, but also of himself as an individual, his family, his friends, and the people he surrounded himself with.

Many of the letters in Rackstraw’s collection – which I confess I have merely scratched the surface of – are surprisingly candid, discussing marriages that happened too soon, regrettable career decisions, and the odd bit of scandal! In other words, all the components necessary to make the historical human. (Or at the very least, to make some deliciously salacious discoveries!).

Sources: Papers of Marjorie Rackstraw, Oxford DNB.