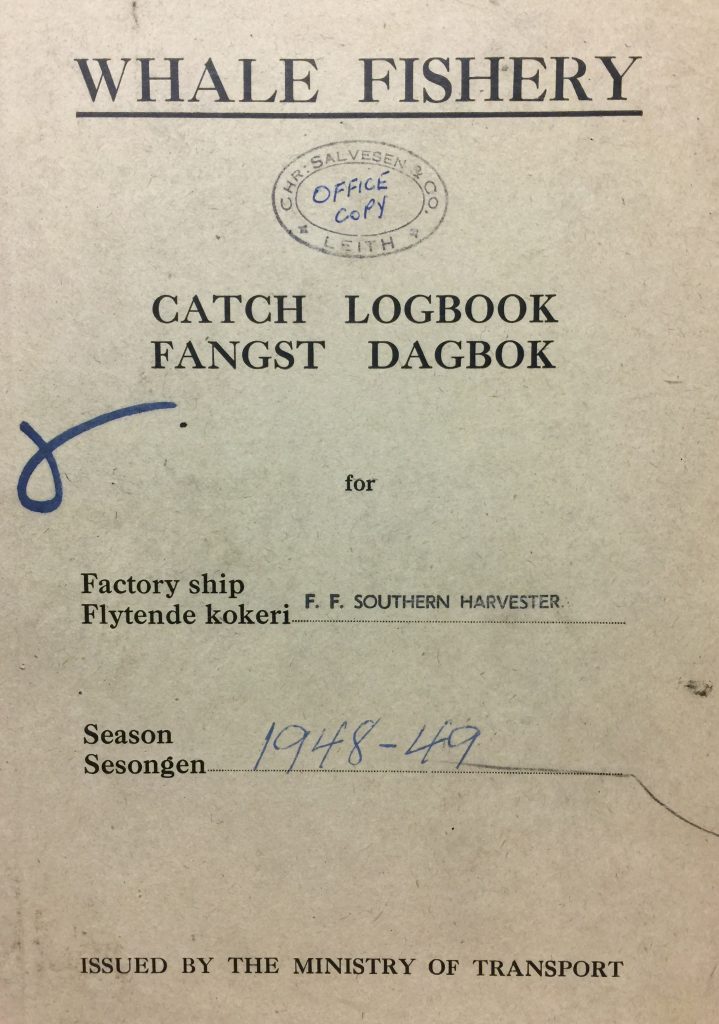

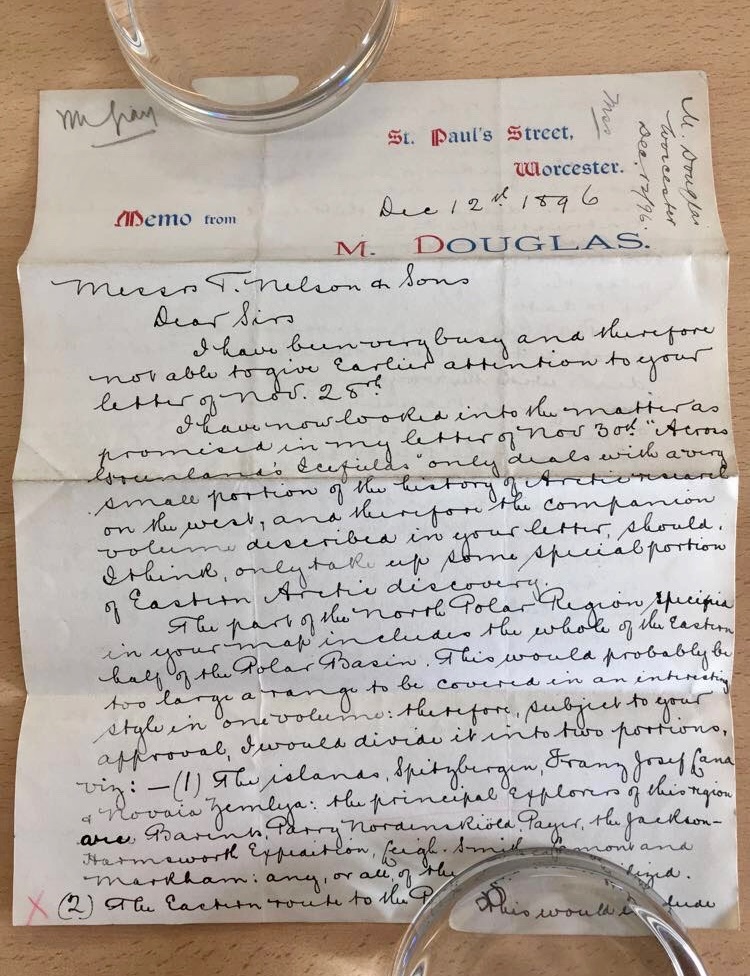

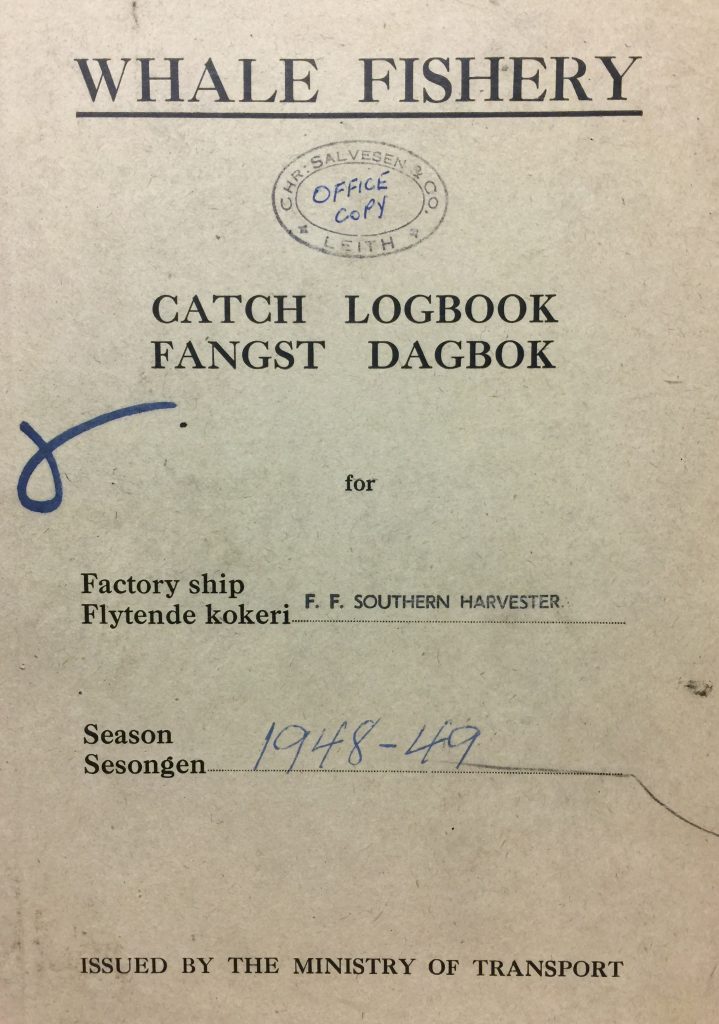

WHALING AS TOLD THROUGH A CATCH LOG-BOOK – THE FANGST DAGBOK of SOUTHERN HARVESTER, SEASON 1948-49, A FLOATING FACTORY OPERATED BY THE SOUTH GEORGIA CO., A SUBSIDIARY OF CHRISTIAN SALVESEN OF LEITH

Catch log-book of the ‘Southern Harvester’ – a stern-slip whaling factory-ship – for season 1948-49. Many of the crew, particularly the officers, were Norwegians and a vessel’s catch log-book, or ‘fangst dagbok’ was bilingual in response to this

A vessel’s log-book provides a record of the most important daily events in its management and operation. Log-books have long been vital to navigation, and most national shipping authorities and admiralties require these to be maintained should radio, radar and global positioning systems (gps) fail. Log-books and their data can be of great importance in any legal case involving maritime accidents or disputes.

Cover of the ‘Southern Harvester’ catch log-book issued by the UK Ministry of Transport and relevant to whaling season 1948-49 [Salvesen Archive]

Log-books maintained by crews involved in whaling operations provided a record of the position of the particular vessel, wind speed and direction, as well as the number of whales taken. The latter statistic would be submitted to the relevant government ministry/ministries and authorities responsible for licensing and quotas. This data would assume greater importance during the early half of the 20th century, particularly during war years (supply of whaling industry by-product), and later on into mid-century as pressure to end commercial whaling became a political issue.

However, a log-book can tell us so much more than weather, navigational and catch data, as the whale catch log-book of the stern-slip factory-ship Southern Harvester illustrates.

The opening page of the 1948-49 catch log-book notes the basic statistics of the floating factory. At the start of the whaling season late-1948 it had a gross tonnage of just over 15,087 tons, and a net tonnage of over 8,092 tons (gross tonnage being the volume of all enclosed spaces of the ship, and net tonnage the volume of all cargo spaces of the ship). The tonnages might vary from season to season depending on whether or not maintenance of the vessel and any refitting or conversions had affected its configuration.

Basic statistics and technical data relating to the ‘Southern Harvester’ captained by Konrad Granøe, which included the information that the vessel was fitted out with 14 whale oil boilers and 2 Hartmann’s Apparatus [Title page of the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

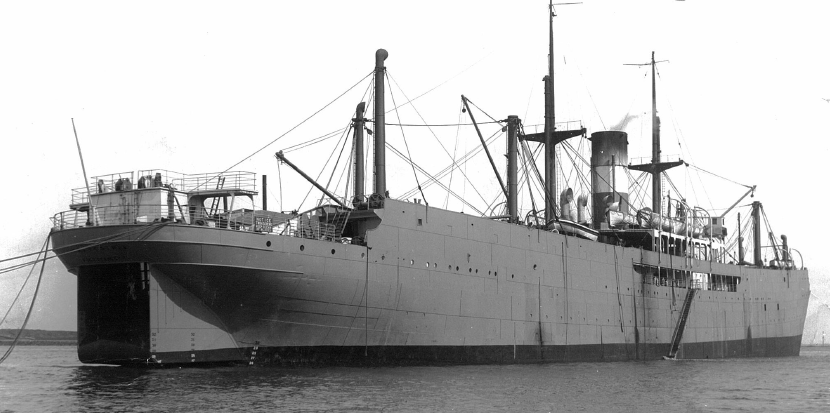

The log-book informs us that the port of registry of the

Southern Harvester was Leith, Scotland. This home port (or

hjemsted) was the place where the details of the ship were officially recorded. Scotland was not where the floating factory was built however.

Southern Harvester was completed in October 1946 by the Furness Shipbuilding Company – on the Tees near Middlesbrough in England – and was the sister ship of

Southern Venturer, also built by Furness in 1945. It had been completed in time for the start of the 1946-47 catch season.

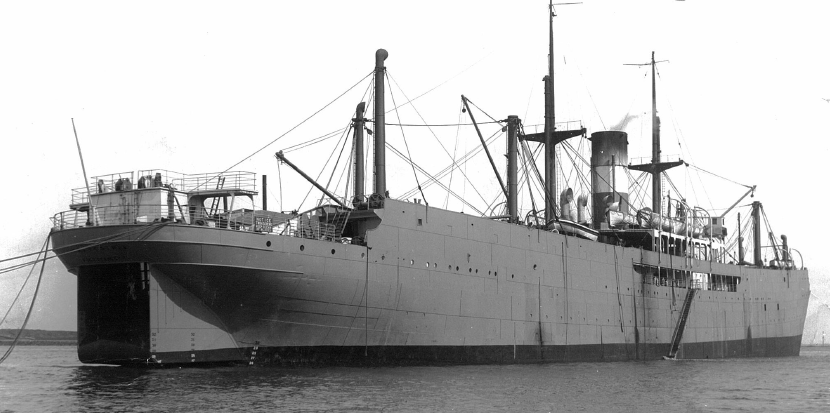

The stern-slip whale factory ship ‘Southern Harvester’. The stern-slipway enabled whales to be hauled directly onto the flensing deck of the vessel where they could be cut down and then processed – ‘worked up’ – below decks in a battery of cookers and boilers [Photographic collection, Salvesen Archive]

Painting of the ‘Southern Venturer’ – sister ship of the ‘Southern Harvester’ – showing the stern-slipway for hauling whales up onto the flensing deck. The painting was the work of George McVey, 1956, and was featured on the cover of the book ‘Salvesen of Leith’, by Wray Vamplew, Scottish Academic Press, Edinburgh and London, 1975

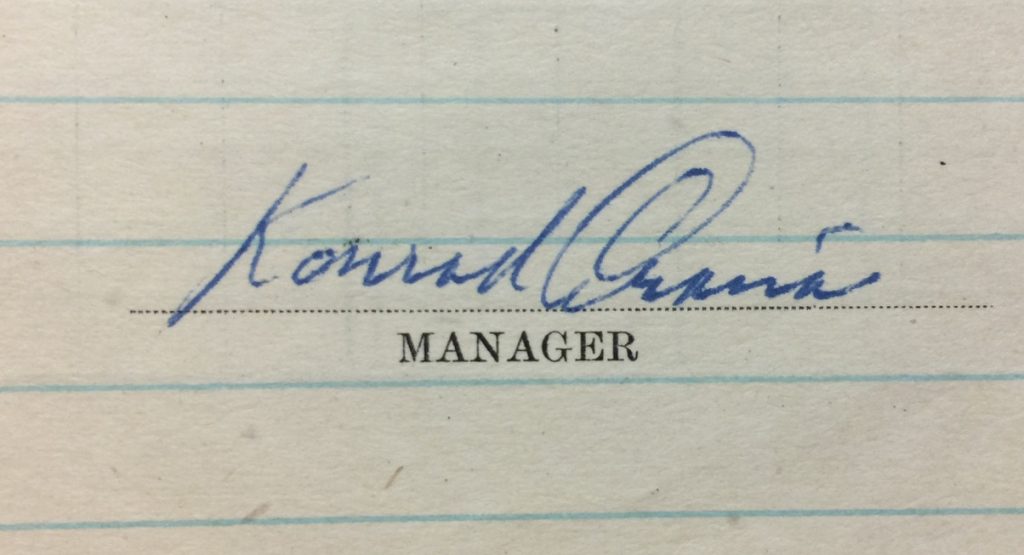

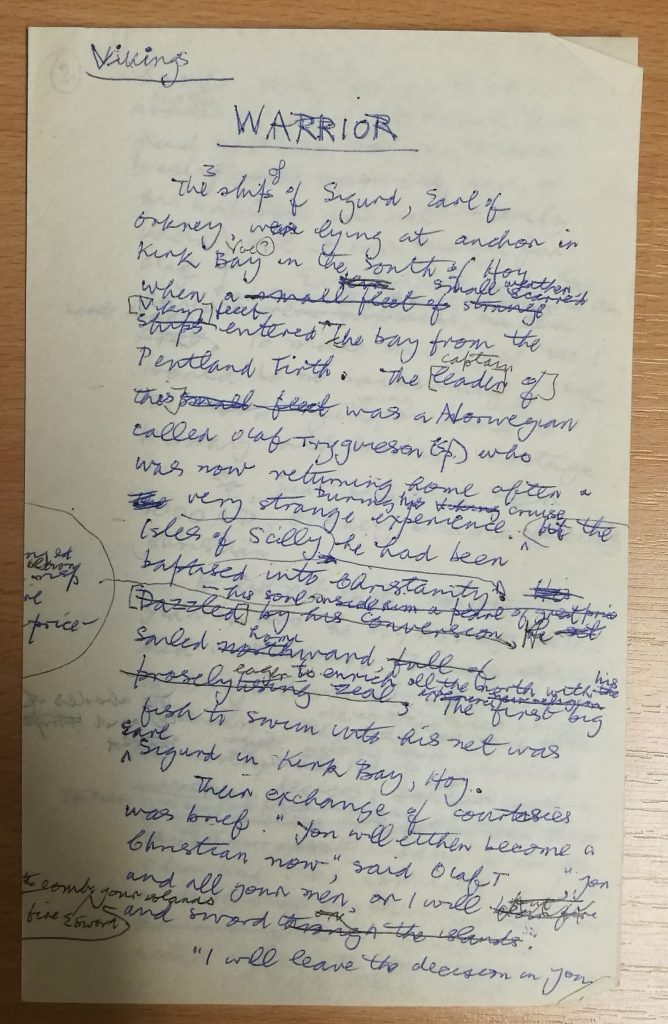

The log-book shows that the 1948-49 season began on 20 November 1948, and ended on 26 March 1949, and that the floating factory Manager (its Captain) had been Konrad Granøe (1889-1961). Granøe was a Salvesen (South Georgia Co.) veteran, serving as Mate aboard the Saragossa during the seasons from 1924 to 1928, attending Masters’ training 1928-29, serving as Manager of Saragossa, New Sevilla, and Salvestria between 1929 and 1936, serving throughout the Second World War, and then serving as Manager of the Southern Harvester from catch season 1947 through to the end of the 1950 season.

The log-book had been written up by another Salvesen veteran, Sigurd Jørgen Bang-Olsen (born in 1902), who had served aboard both the Southern Harvester and Southern Venturer during various catch seasons from 1945 until 1963, and whose career with Salvesen began in Leith Harbour, South Georgia, in 1926. He experienced shore-station work at Leith harbour until 1930 and again during the 1940s (also at the offices of Tønsberg Hvalfangeri, South Georgia) and from 1950 until 1957.

Completed in 1913, the Salvesen vessel ‘Salvestria’ had been captained by Konrad Granøe in the 1930s, and it was lost August 1940 after it struck a mine in the Forth estuary off Inchkeith during the last leg of a voyage from Aruba in the Caribbean to Grangemouth. Sigurd Jørgen Bang-Olsen had also served on ‘Salvestria’ [Photographic collection, Salvesen Archive]

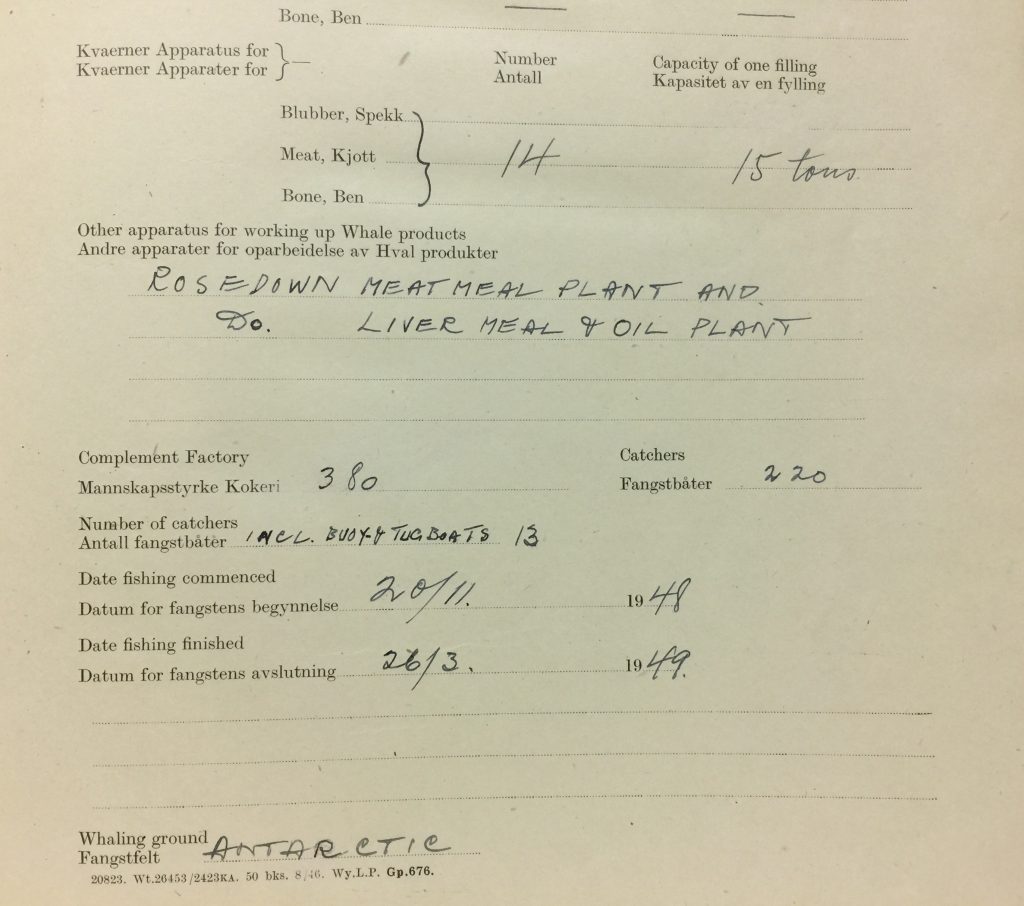

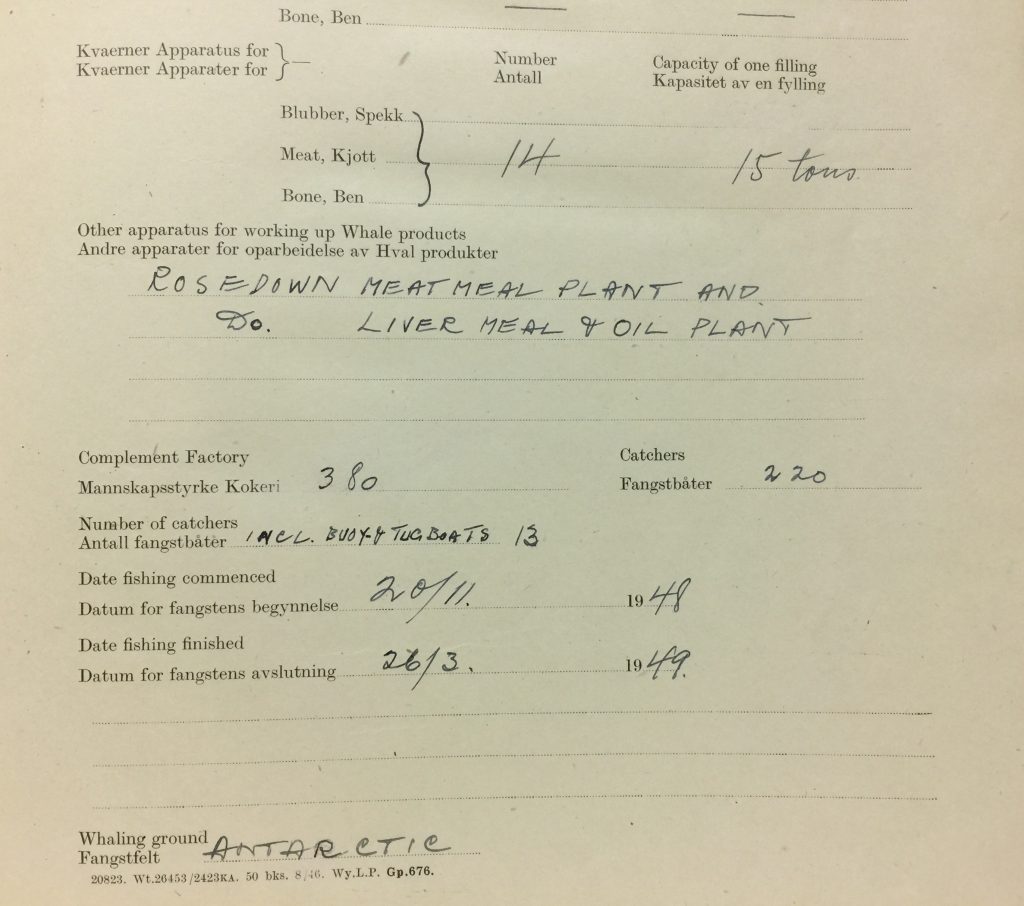

The 1948-49 log-book indicates that

Southern Harvester had been fitted with both Hartmann’s Apparatus and Kvaerner’s Apparatus for the rendering of whale carcasses. The vessel also operated a Rosedown Meat Meal Plant and Liver Meal and Oil Plant. Aboard the floating factory operating for the season in the Southern Ocean and Antarctic whaling grounds (or

fangstfelt) was a complement of 380 crew, supported by 220 crew aboard 13 supporting vessels. The support vessels in question were whale-catchers, buoy boats, and tug-boats (the latter two used for rounding up, holding and towing the whales killed during a hunt).

Technical data relating to the ‘Southern Harvester’ indicating that the vessel was kitted out with a Rosedown Meatmeal Plant and Liver Meal and Oil Plant [Title page of the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

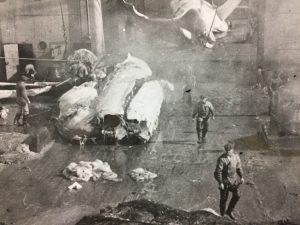

So-called ‘apparatus cooking’ using the Hartmann process – cookers constructed originally by R. A. Hartmann, Berlin, Germany, and specifically for floating factories – took up much less space than on shore-based whaling stations. The Hartmann’s Apparatus treated whale carcasses and slaughterhouse waste, boiling down whale flesh and bone, and breaking up content into such small particles that they were almost liquidised.

Hartmann equipment for whale oil production shown in an advertisement stating that there were 4 such apparatus aboard the ‘Southern Venturer’, which was the sister ship of ‘Southern Harvester’ [From a copy of ‘Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende’ / ‘Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, Salvesen Archive]

Whale meat was a by-product of the very much more lucrative whale oil industry, and the meat from carcasses aboard the

Southern Harvester was processed using the Rosedown Meatmeal Plant and Liver Meal and Oil Plant, as well as the Kvaerner ‘digester’. The Norwegian Kvaerner Apparatus produced whale oil, bone meal, meat powder, and gravy concentrate, wasting little in the processing of a whales carcass.

Kvaerner Apparatus on railway wagons leaving the Kvaerner Works in Oslo, Norway [Advertisement from a copy of ‘Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende’ / ‘Norwegian Whaling Gazette’, Salvesen Archive]

Processing of whales – ‘working up whales’ – aboard an early floating factory. Processing was conducted below decks aboard the ‘modern’ vessels constructed during the 1940s [Photograph among material gifted by Sir Gerald Elliot in 2012, Salvesen Archive]

In addition to providing information about the technical equipment aboard the floating factory, the log-book offers data about local weather conditions at a particular place and at a set time each day. For example, on Sunday 12 December 1948,

Southern Harvester had been located at latitude 60° 35′ South and longitude 79°02′ East, where it was encountering ‘a few small’ icebergs in cloudy and clear conditions, with a Force 3 wind from the North West. That particular location was roughly half-way between the coast of Antarctica and Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI), in the Southern Ocean (in this case, part of the ocean south of the Indian Ocean). The HIMI were some of the remotest islands in the world, around 450kms from the Kerguelen Islands, and which a year earlier in 1947 had been transferred by the UK to Australia.

Page of the ‘Southern Harvester’ floating factory whaling log-book showing the vessel’s position on 12 December 1948. Latitude 60° 35′ South and longitude 79°02′ East was a location half-way between the Davis Station, Antarctica, and Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI), in the Southern Indian Ocean [In the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

The log-book tells us that at the end of a 24-hour period logged on Sunday 12 December 1948,

Southern Harvester had 6 whales still to be processed (‘worked up’). At the start of that 24-hour period, 9 whales had been ‘in hand’ with the supporting whale-catchers, buoy boats, and tug-boats together engaged in rounding them up. These had been Sperm Whales (the log-book offering separate columns to be completed for ‘B’ or Blue Whales, ‘F’ for Fin Whales, ‘H’ for Humpback Whales, and ‘S’ for Sperm Whales).

In addition to the 9 ‘in hand’ at the start of the period, another 10 Sperm Whales had been killed over the course of the day (making 19 in total), and over the day 13 Sperm Whales of the total had been processed.

The above page of the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book informs us that ‘baleen whaling commenced 15 December 1948’. Sperm Whales (abbreviated as ‘S’ in the data) are of course toothed whales, Odontoceti. From 15 December, the log-book showed the catching of Blue Whales (‘B’) and Fin Whales (‘F’) which, together with Sei, Humpback, Bowhead, Gray, Minke, and others, are all baleen whales, Mysticeti [Page in the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

The weather conditions meticulously recorded in this catch log-book – together with similar data from the vessels of several other companies and operations – have helped modern climatologists to better understand climate change and polar and sub-polar weather patterns. The data that crews recorded over a number of decades included precise longitude and latitude measurements, weather conditions, the presence of icebergs and where the edge of the ice shelf was encountered. That data can be compared with current conditions, answering the question of, for example, whether or not there is sea ice today in the places where whalers saw sea ice decades and decades ago.

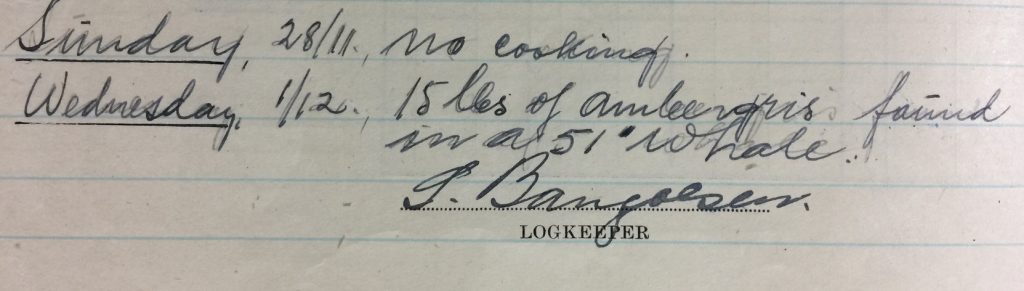

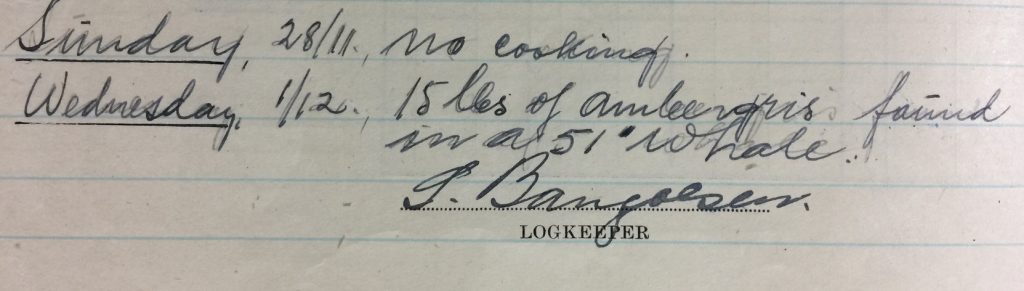

The catch log-book, kept up-to-date by the log-keeper, Sigurd Jørgen Bang-Olsen, has noted that on 12 December 1948 a 6.8 kilogram mass of ambergris had been found in a whale (the ambergris noted as being 15 pounds imperial weight). Ambergris is formed from a secretion of the bile duct in the intestines of the sperm whale, and would normally be passed in fecal matter. Ambergris acquires a sweet, earthy scent as it ages and so had been very highly valued by perfumers as a fixative allowing the scent to last much longer [Page in the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

Similarly, biologists interested in predicting the rate of whale population recovery, and the modelling of historical abundance and distribution, have taken geographic locations and whale catch numbers from log-books and combined that old data with modern technology – such as geographic information system (GIS) – to provide new insights into whale distributions.

Signature of Konrad Granøe (1889-1961), Manager of the ‘Southern Harvester’ [Page in the ‘Southern Harvester’ log-book, 1948-49, Salvesen Archive]

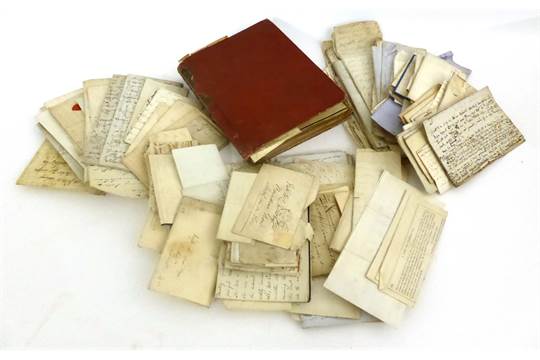

In 2016, the ship log-books, whale catch log-books and a small number of ice charts in the Salvesen Archive underwent rigorous research by scholars from the University of Exeter, part of the RECLAIM project (

RECovery of

Logbooks

And

International

Marine data). The aim of RECLAIM was to locate and image historical maritime log-books and related marine data and metadata from archives across the globe, and to digitise the meteorological and oceanographic observations for merger into the International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set (ICOADS) and for use in climate research.

Graeme D. Eddie, Honorary Fellow, CRC, engaging with the Salvesen Archive of maritime trading and whaling

References:

In the creation of this post the following resources were used: (1) Ogden, Lesley Evans. ‘New data from old treasures: Whaling logbooks’, BioScience, Vol.66, Issue 7, 1 July 20-16, p. 620; (2) Wilkinson, Clive. ‘Ice and Meteorological Data in the Christian Salvesen Archive, University of Edinburgh’, Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia Norwich UK & Faculty of Natural Resources, Catholic University of Valparaiso, Chile, 2013; (3) RECLAIM project, https://icoads.noaa.gov/reclaim/ [accessed 25 September 2019]; and (4) ‘The 19th-century whaling logbooks that could help scientists’, The Guardian, Thursday 17 December 2015.

If you have enjoyed reading this post, check out previous ones about the Salvesen Archive, or using Salvesen Archive content, which have been posted by units across CRC since 2014:

Salvesen Archive – 50 years at Edinburgh University Library – 1969-2019 May 2019

Cinema at the whaling stations, South Georgia August 2016

Exploring the explorer – Traces of Ernest Shackleton in our collections May 2016

Maritime difficulties during the First World War – Christian Salvesen & Co. October 2015

Talk on the Salvesen Archive to members of the South Georgia Association November 2015

‘Empire Kingsley’ – 70th anniversary of sinking on 23 March 1945 March 2015

Pipe bombs, hurt sternframes, peas, penguins, stoways and cookery books: the Salvesen Archive July 2014

Whale hunting: New documentary for broadcast on BBC Four June 2014

Penguins and social life May 2014