As many of us face the challenge of managing our mental and physical well-being during the current Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, we look to the doyenne of movement and pioneer of dance, Margaret Morris, for inspiration…

In 2018, a YouGov online poll (based on a sample of 4619 participants) recorded that 74% of people have felt so stressed that they have been overwhelmed or unable to cope, 61% felt anxious and 37% lonely due to isolation. A further 36% of adults who reported stress in the previous year cited either their own or a friend/relative’s long-term health condition as a factor, rising to 40% in adults over 55. Housing worries were another key source of anxiety. In 2013, there were 8.2 million recorded cases of anxiety in the UK.

In 2018, a YouGov online poll (based on a sample of 4619 participants) recorded that 74% of people have felt so stressed that they have been overwhelmed or unable to cope, 61% felt anxious and 37% lonely due to isolation. A further 36% of adults who reported stress in the previous year cited either their own or a friend/relative’s long-term health condition as a factor, rising to 40% in adults over 55. Housing worries were another key source of anxiety. In 2013, there were 8.2 million recorded cases of anxiety in the UK.

In 2020, we can now add the stresses and strains of coronavirus (COVID-19) into the mental health mix. There is little doubt that current measures around social distancing and restrictions on movement – in place to protect ourselves and others from coronavirus – are exacerbating the collective strain on mental and physical well-being. Mental health organisation websites (such as the Mental Health Foundation, Mind, and the Scottish Association for Mental Health) are all leading with how to protect our mental well-being during the coronavirus pandemic. On 27 March 2020, the Scottish Government announced an additional £3.8 million investment to expand support for digital mental health services specifically in response to further demand as a result of the current crisis.

In 2020, we can now add the stresses and strains of coronavirus (COVID-19) into the mental health mix. There is little doubt that current measures around social distancing and restrictions on movement – in place to protect ourselves and others from coronavirus – are exacerbating the collective strain on mental and physical well-being. Mental health organisation websites (such as the Mental Health Foundation, Mind, and the Scottish Association for Mental Health) are all leading with how to protect our mental well-being during the coronavirus pandemic. On 27 March 2020, the Scottish Government announced an additional £3.8 million investment to expand support for digital mental health services specifically in response to further demand as a result of the current crisis.

As our first-hand experience of social isolation informs our understanding of its impact, many of us are developing a new found empathy for those who had been living in social isolation pre-coronavirus. For those of us accustomed to leading active lives and moving around freely, we are now having to consider carefully the new risks associated with moving and exercising outwith our homes. For many of us, physical movement will be at the very bottom of our priority list as we juggle all of our other commitments. After all, just thinking about how to incorporate physical movement into our new daily routine (if we have managed to establish one) can be mentally exhausting given our work, family, child-care, pet-care, carer, domestic, social media, volunteering, and the new plethora of video group-chat catch-up commitments. That’s before we even register the anxiety around actually becoming infected with or transmitting coronavirus.

There are many studies which have shown that doing physical activity can improve mental health by aiding sleep, releasing feel-good hormones, distracting our brains from intrusive and racing thoughts, improving self-esteem, and reducing the risk of depression. All even more important in the current environment. How then, at this time of crisis, do we move physical and mental well-being up the priority list? For help, we decided to look to our archives and into the past. We look to the great doyenne of all things movement and pioneer of dance, Margaret Morris (1891-1980), for some inspiration and guidance.

Front cover of Margaret Morris’ Basic Physical Training, 1937, courtesy of Culture Perth and Kinross

Ideas around the integration of mind and body are not new. In the 1920s, Margaret Morris, a dancer, choreographer and teacher, was part of a wider campaign that promoted health via ‘movement, wholefood, fresh air etc’. Morris developed her ‘Margaret Morris Movement’ method in which students studied form, line, colour, movement, music, rhythm, sound and composition. When she was interviewed in 1926 for Architecture: the magazine of architecture, the applied arts and crafts, Margaret Morris highlighted one of the primary problems in the area of physical movement which was, (and still is), ‘how can physical exercise be made interesting?’ Morris remarked in her 1937 publication Basic Physical Training, ‘corrective exercises have…excellent results when persisted in long enough – but they are terribly boring to do…’ Morris was convinced that interest could only be done by bringing the creative or artistic element; which she argued was not so difficult or far-fetched as it may at first appear. Underlying her approach was the inter-relation and harmony of all the arts. ‘All movements performed for the establishment of health…must combine the aesthetic as well as the medical values of movement.’

Morris developed and refined her method throughout her lifetime. By 1938, four divisions of Margaret Morris Movement had been established: normal, medical, athletic and aesthetic, all of which were interrelated. Morris propounded the remedial and health benefits of dance and her particular movement method as she witnessed improvements in her dancers’ posture and general health. Morris developed a dance system which, she argued, was more natural than classical ballet and allowed for all the possibilities of movement, including spring and balance, without artificialities or contortions – to allow a true freedom of expression. Many of us are currently experiencing high emotional states, but may be finding it difficult to express ourselves in words. Dance allows individuals to express powerful emotions through their physical bodies perhaps more instinctively and intuitively, and our bodies provide a physical medium through which pent up emotion may be released.

Central to the Margaret Morris Movement method is the science of breathing, and she advocated the teaching of correct breathing before anything else so that the breath is synchronised with movement. Many of the movements she devised are based on a ‘twist of the trunk, with counter-balancing arm and leg movements’. Writing in her book Roar (2016), about female physiology, health and fitness performance, Dr Stacy T. Sims tells us that ‘when our entire torso (collarbone to hip) is strong and solid, so are you.’ Unlike many other sports or physical activities, dance develops core strength as the foundation of every other move. Morris underlines the importance of the lungs, the abdomen and feet in Basic Physical Training claiming, ‘their efficient functioning is unquestionably of the first importance for success in any form of physical activity whatsoever.’

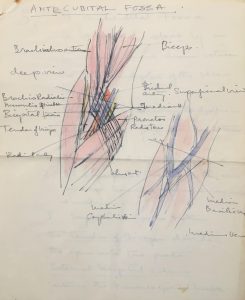

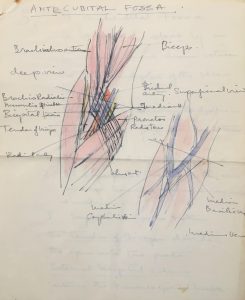

Margaret Morris Movement was informed by Morris’ deep understanding of human anatomy, illustrated here in one of her many anatomical drawings, underaken as part of her physiotherapy studies. Courtesy of Culture Perth and Kinross

From 1925 Morris began to demonstrate remedial qualities of her movement method to health professionals. In 1930 she qualified as a physiotherapist and by 1937 she was invited to join the National Council for Physical Education. By 1939 Margaret Morris had authored or co-authored a number of publications which described the Margaret Morris Movement method and explained its application to a range of physical activities including dancing, skiing, maternity and post-operative exercises, tennis and basic physical training. The continuing relevance of her ideas was recognised in 2013 in the New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy in which her ‘maternity exercises’ from 1938, are considered to translate well to the present day, with more evidence to support their use in some instances. Margaret Morris Movement dance teachers continue to teach her technique and dances today to encourage the love of dance and movement for health benefits, satisfaction and performance. You can read more about Margaret Morris and the current work of Margaret Morris Movement International Ltd on their website.

While our freedom of movement may be geographically constrained, why not let Margaret Morris and her dancers inspire you to explore a physical freedom of movement and expression within your home? There is wonderful video footage of Margaret Morris demonstrations to be found online via British Pathé. Perhaps put on some music, breathe a little more deeply and rhythmically, give your trunk a little twist, counter-balance your limbs, think a little less, move a little more. Dance your way physically, through your body, to a better mental space. Alone or with your family, or dare I mention it, shared via video call. Test the assumption of intellectual superiority suggested by Descartes when he declared “I think, therefore I am” and try out our favoured alternative: “I move, therefore I am”.

We hope Margaret Morris will inspire you to add a little physical movement to your day. Stay safe, stay well, stay home – keep moving.

Elaine MacGillivray – Project Archivist

Acknowledgements

The Margaret Morris Archive was gifted by the International Association of Margaret Morris Movement to our project partner Culture Perth and Kinross in 2010. Images are courtesy of Culture Perth and Kinross and Margaret Morris Movement International Limited.

The Margaret Morris Archive is being catalogued as part of our Wellcome Research Resource-funded ‘Body Language’ project. The archive is held at the Fergusson Gallery in Perth. The Gallery is currently closed in line with Scottish Government guidance relating to the coronavirus pandemic. Updated information regarding re-opening will be published on the Culture Perth and Kinross Museums web-pages when available.

References

Morris, Margaret and Daniels, Fred, Margaret Morris Dancing, (Kegan Paul, 1926)

Morris, Margaret, The Notation of Movement, (Kegan Paul, 1928)

Morris, Margaret and Falkner, Hans, Skiing Exercises, (Heinemann, 1934)

Morris, Margaret and Randell, M., Maternity and Post-Operative Exercises, (Heineman, 1936)

Morris,Margaret, Basic Physical Training, (Heinemann, 1937)

Morris, Margaret, My Life in Movement (1969)

Power, Richenda, Healthy Motion: Images of ‘natural’ and ‘cultured’ movement in early twentieth-century Britain, in Women’s Studies International Forum, Vol 19, Issue 5, (Sept-Oct 1996)

Simpson, Betty and Whitfield, Frank, Notes on the theory of teaching Margaret Morris Movement (1936)

Sims, Stacy T., Roar, (Rodale, 2016)

Hay-Smith, E Jean C, Maternity Exercises 75 years on: what has changed and what does experimental evidence tell us? in New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy, Vol 41, Number 1, (March 2013)

Miss Margaret Morris at Crosby Hall in The Academy, (25 May 1912), p.658

Architecture, a magazine of architecture and the applied arts and crafts, Vol 4, Issue 10, (London, February 1926).

Margaret Morris Movement International Ltd website

Mental Health Foundation website

Mind: the mental health charity website

The Scottish Association for Mental Health website

The Scottish Government website (news web-pages)

In 2018, a

In 2018, a  In 2020, we can now add the stresses and strains of coronavirus (COVID-19) into the mental health mix. There is little doubt that current measures around social distancing and restrictions on movement – in place to protect ourselves and others from coronavirus – are exacerbating the collective strain on mental and physical well-being. Mental health organisation websites (such as the

In 2020, we can now add the stresses and strains of coronavirus (COVID-19) into the mental health mix. There is little doubt that current measures around social distancing and restrictions on movement – in place to protect ourselves and others from coronavirus – are exacerbating the collective strain on mental and physical well-being. Mental health organisation websites (such as the